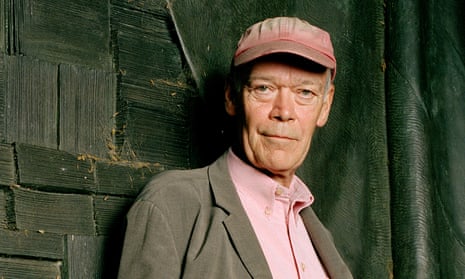

Jonathan Raban, who has died this week at the age of 80, was one of a generation of writers who helped to drag travel writing away from its hotel-reviewing, holiday-brochure corridor and into the halls of literature. Colin Thubron, Paul Theroux, Redmond O’Hanlon and Bruce Chatwin were among those (almost all men) who in the late 1970s and early 1980s resurrected the journey as one of the great narrative structures. They produced books that celebrate big ideas, remote places and the endless and ageless diversity of our planet. In Raban’s case, he did it with a view of the world that was both darkly comic and sardonic, delivered in prose that can pierce your heart with its accuracy.

As well as his travel books, Raban wrote dazzling essays and criticism, spotting writers’ weaknesses but always relishing success when he saw it on the page. John Updike “comes to grip with the contrary fabric of things with a kind of intelligent wonder”. Byron “had a genius for turning his entire life into a grand retrospective exhibition”.

I never met Raban but we had the same agent – the charming and famously laconic Gillon Aitken. Once, when Gillon was staying with me in Cornwall, I proposed a day’s sailing in my old wooden boat. “No,” said Gillon. “Jonathan took me out sailing. Never again, Philip, never again.”

Raban was the first to admit that – to begin with at least – he was not a natural seaman, but said: “I like to travel as much as I possibly can in a boat small enough to manage on my own.” He recounted his anxieties as openly as the triumphs and beauty of being at sea, recognising the value of plain description: ‘The lightless water and the lightless sky formed an evenly laid wash of flannel-grey…”

Above all, boats allowed him an outsider’s view of the places and people he encountered ashore. His magnificent book Coasting is the story of his circumnavigation of the UK in an old ketch, in which he skewered all the lingering pomp and crusty self-importance of 1980s Britain.

He wrote with disarming candour about everything, including himself. Who can forget the scene in Coasting when Theroux, a friend, comes aboard? Theroux was travelling for a similar, land-based book about Britain. They were both deeply suspicious, sniffing around each other like two dogs. Then Theroux told an anecdote and the atmosphere flipped. “Suddenly, apropos of nothing,” recalled Raban, “he came to life.”

Even more striking is the scene in his 1999 book Passage to Juneau when, after a thousand miles of lone sailing, Raban was joined in Alaska by his wife and young daughter. While they watched the girl rock back and forth on a park swing, his wife said: “I’m leaving you.” It is a devastating finale to what is, for me at least, not only his finest book but one of the best works of nonfiction of the last 50 years. The full range of what travel writing can do is on display – the spectacular coastline, the perils of the journey, the cast of sea-shaped misfits and the deeply researched ethnographic passages. There is also – as well as his wife’s announcement – a chapter about flying back to the UK to visit his dying father. All is recounted with the same clarity. If there are vague questions over whether this is all too personal, they are overshadowed by the intense honesty. Raban believed in the power of the written word, in its capacity for redemption and transcendence, and he had the skill to use it.