To hear an audio spoken word version of this post, click here.

By now, you are probably as tired of reading my complaints about forecasting as I am of writing them. So instead of my usual recap of last year’s terrible predictions, I am going to make a few constructive suggestions as to better ways to think about the inherently unknowable future.

1. Start with a few simple rules. For Wall Street investing and economic modelers, that includes: a) Sharing the model’s past performance; b) Acknowledging the unknown variables that confront your model; c) Admitting any known biases, recognizing the possibility of unknown ones. Once you have that out of the way, you can at least make a good faith effort to “model the future.”

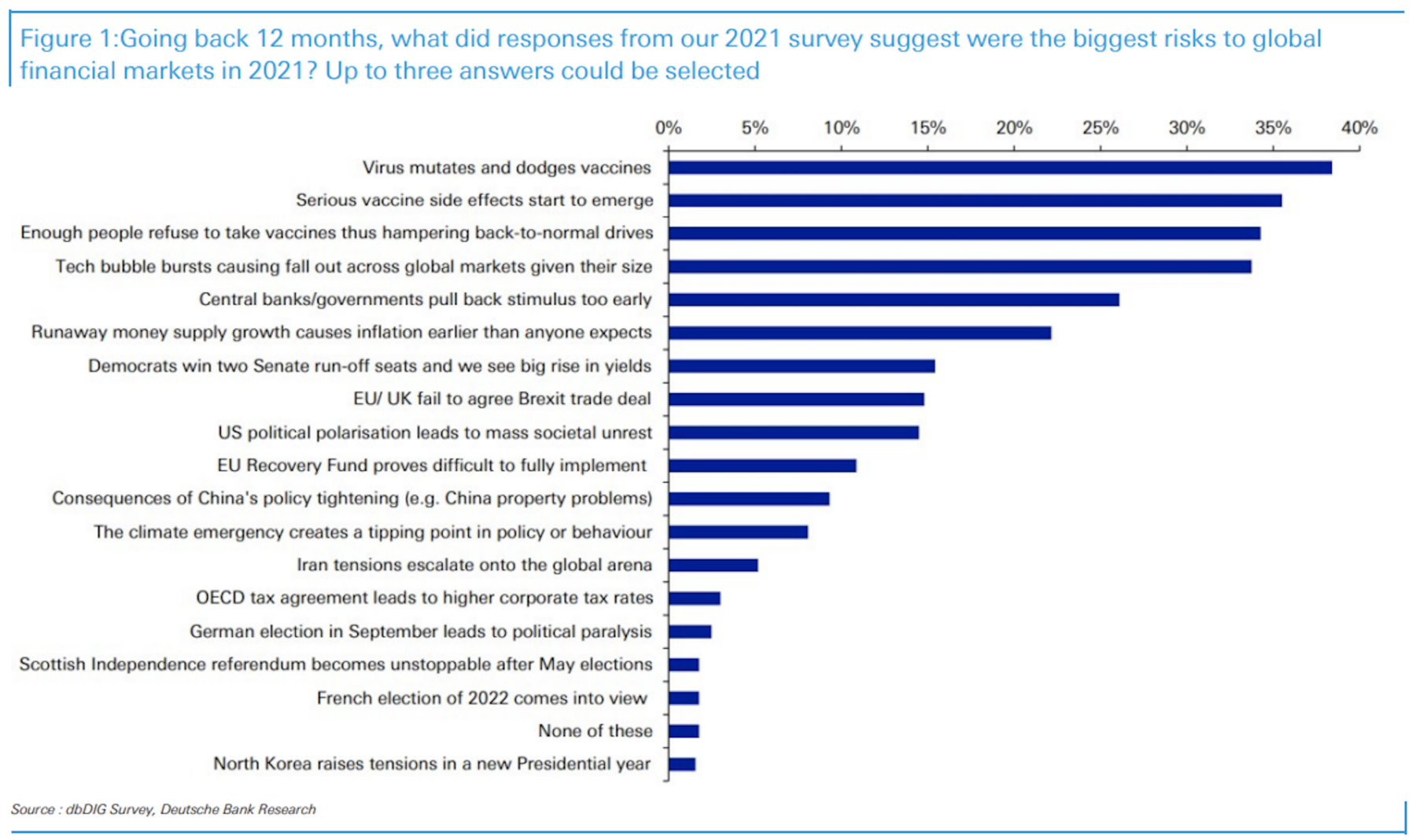

2. Think in terms of probabilities (not outcomes). I like the approach that Jim Reid of Deutsche Bank takes (see chart at top). He surveys his clients, asking what they are looking at as possible risks for the coming year.

Of course, the usual biases are inherent in any survey; a year ago, the top 3 concerns were all pandemic related (e.g., Recency Bias): Virus mutates/dodges vaccine (38%); Vaxx side effects (36%); Vaxx refusal hampers recovery (34%). The Tech bubble bursting was #4 at 26%. And very few people had inflation (22%), and ranked 6th on the list, as a high threat. The key takeaway is that not only do we not know what is going to be most or least significant, we very often have no idea what might become the biggest story of the day/month/year.

3. Stop investing based on forecasts: The biggest risk facing investors is not that forecasts will be wrong — we know they will. It’s that investors tend to marry their predictions and manage their portfolios accordingly. Rather than looking at a universe of opportunities and risks, they become confirmation bias machines, hunting out what agrees with their prediction. It is a terrible way to manage a portfolio and puts ego above profitable investing.

4. Can we please stop with the “Uncertainty” nonsense? The future is always uncertain. Whenever you hear this phrase, you should automatically translate it into: “We are really nervous about what might happen.” Discussions about “Uncertainty” are far more revealing about the speaker than they are about the future.

5. Who Is Often Right? Pay Attention to those who have a method for thinking about the unknown. For example, the group Prof Philip Tetlock oversees at The Decision Lab & Wharton has made a science out of improving the process behind making forecasts. “The peculiar thing in the real world is how comfortable we are at making pretty strong factual claims,” says Tetlock that turns out to be wrong. Your claims to know the future is implicitly about “how the world would have unfolded in an alternative universe to which you have no empirical access, only your imagination.”

Maybe more on this later (or not) . . .

Previously:

Rules for Forecasters (April 8, 2019)

There’s nothing new about uncertainty (July 14, 2012)

The Uncertainty Myth (November 10, 2010)

Do You Wanna Be Right, or Do You Wanna Make Money? (October 6, 2010)

Forecasting & Prediction Discussions

click for audio