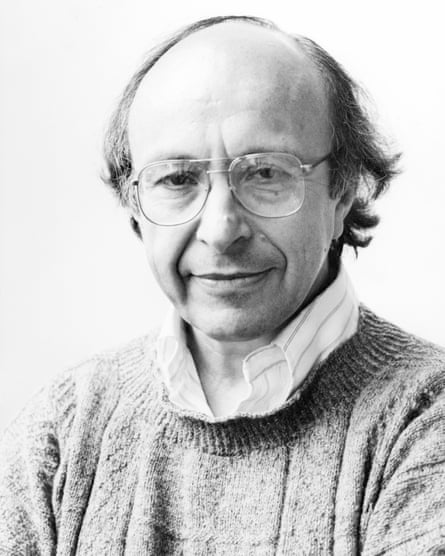

Jonathan Mirsky, the Observer’s former China correspondent who has died aged 88, was acutely aware of the mounting danger from the bullets criss-crossing Tiananmen Square on 4 June 1989 as units of the People’s Liberation Army were sent in to break up the protests. He was aware too that he desperately needed to get his copy to London.

Writing about the experience 30 years later, Mirsky admitted that few at first had any sense of the scale of the violence that was being unleashed either on the students in the square. All that, however, was to change quickly.

“At three in the morning I feared I might be killed,” Mirsky recalled. “But I knew I must file the story for the paper. As the silver streaks of bullets lighted the darkness, a student next to me said: ‘Don’t worry. The soldiers are using blanks.’ A few seconds later he slumped over, dead, with a wet red circle on his chest.

“As I began to leave the square,” Mirsky continued, “I came to a knot of armed police whose trouser bottoms had been ignited by Molotov cocktails thrown by workers. When they saw me passing they shouted at me to stop. I said: “Don’t hit me. I’m a journalist.” Their officer shouted back, in Chinese: “Fuck you, we’re going to kill you.”

“As they began beating me with their rubber truncheons, the officer shot fallen demonstrators. My left arm was fractured, half-a-dozen teeth were knocked out and I thought I was finished. But a British journalist running out of the square swerved, took my arm, and led me away. I managed to dictate my story by phone to an Observer copytaker who asked me: ‘Hey mate, is everything OK?’”

Warm, witty and deeply intellectual, Mirsky was a historian by training and inclination who turned from academia to journalism, a somewhat unusual figure in the Observer of the time. As Jonathan Steele explained in his obituary of Mirsky for the Guardian, Mirsky had “begun as an early and prominent academic critic of the US’s role in the Vietnam war, starring in numerous protest marches and campus teach-ins.”

Although at first predisposed to be sympathetic to Maoism in China, a six-week guided trip for young China researchers in 1972 convinced him that something darker was at work beneath the official claims of progress. That would become a hallmark of Mirsky throughout his long and distinguished career: a constant and active interrogation of his own assumptions, refining his understanding of China and his own reporting. One example was a piece for the New York Review of Books on the 25th anniversary of Tiananmen Square describing the heady days in May that preceded the massacre.

“In late May, I and several other journalists watched those tanks turn away, along with truckloads of soldiers, who had been blocked and rebuked in the suburbs before they, too, drove off.

“Now I really thought the Party was finished. How wrong we were – foreign reporters, China-watchers abroad, and many Chinese themselves.”

Born in New York in 1932 and educated at Columbia University, Cambridge University, and the University of Pennsylvania, Mirsky taught Chinese and Vietnamese history, comparative literature, and Chinese at Cambridge University, the University of Pennsylvania, and Dartmouth College, where he was recalled as a warm and generous teacher. Failing to get tenure at Dartmouth, where he had been a prominent anti-war activist on campus, Mirsky moved to London in 1975 and a new career in journalism. He wrote on Chinese-occupied Tibet for the Observer, based on a number of reporting trips, understanding – as Steele explains – that the repression in Tibet was not “just about communism but the racist imperialism by Han Chinese towards ethnic minorities”.

But his greatest legacies would be his indictments of the China that Mao had fashioned and Tiananmen Square.

In a review of Frank Dikötter’s The Tragedy of Liberation in the Literary Review in 2013 he linked those preoccupations across the years in discussing the Maoist use of “thought reform” with chilling reference to a friend’s experience of how dictatorship refashions reality:

“Robert Ford, the Dalai Lama’s radio operator,” said Mirsky, “was detained for four years after the Chinese occupation of Tibet and has described what happened to his mind: ‘When you’re being spiritually tortured by thought reform, there’s nowhere you can go. It affects you at the most profound, deepest levels and attacks your very identity.’

“Many young Chinese, parroting the official line, maintain that what happened in Tiananmen Square on 3-4 June 1989 was a ‘riot in which bad people shot our police and soldiers’.”

In the end, the Chinese Communist Party had enough, banning Mirsky from China and going so far, in 2010, as to remove a four-page article he had written for Newsweek from copies on sale in China. He recounted the episode in the New York Review of Books. “In late December, a foreign correspondent in Beijing emailed me to say that a four-page article on China I’d written for a special New Year’s edition of Newsweek had been carefully torn from each of the 731 copies of the magazine on sale in China. Now, friends and colleagues are telling me what an honour it is to have one’s writing banned in the People’s Republic.”