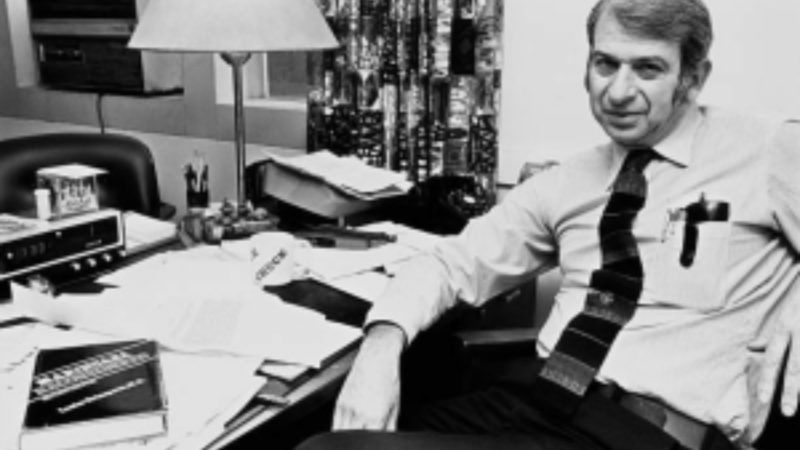

RIP Lester Grinspoon, Who Encouraged Americans To Reconsider Demonized Drugs

For half a century, Grinspoon tirelessly advocated a more rational and tolerant approach to marijuana and other psychoactive substances.

Lester Grinspoon, a leading drug policy reformer who died yesterday at the age of 92, was an optimist. "Whatever the cultural conditions that have made it possible, there is no doubt that the discussion about marihuana has become much more sensible," Grinspoon wrote in 1977. "If the trend continues, it is likely that within a decade marihuana will be sold in the United States as a legal intoxicant."

It turned out that Grinspoon was off by a few decades. He did not anticipate the reaction against adolescent pot smoking that would lead to an intensified war on weed during the Reagan administration, when public support for legalization dropped after rising during the 1970s. But Grinspoon lived to see marijuana become a legal intoxicant in 11 states, nine of which have government-licensed shops serving recreational consumers. Marijuana retailers not only are legitimate businesses in those nine states; they were deemed "essential" during COVID-19 lockdowns in all but one, meaning they were allowed to stay open as other merchants were forced to close.

That is a remarkable development after a century of pot prohibition, which began at the state level in 1911 and culminated in the federal Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. The ongoing collapse of that regime is due in no small part to Grinspoon's tenacious advocacy of a more rational and tolerant approach to America's most popular illegal drug.

Grinspoon's career as a reformer spanned half a century, beginning with his 1971 book Marihuana Reconsidered. When he published that book, Grinspoon was a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. That respectable perch gave him credibility as he made a case that was still highly controversial at a time when nearly nine out of 10 Americans thought marijuana should remain illegal.

Grinspoon, whose old-fashioned spelling of the drug's name harked back to the era of Reefer Madness, originally set out to present credible evidence of marijuana's harms to pot-smoking kids who were ignoring the government's warnings. "I was concerned about all these young people who were using marijuana and destroying themselves," he told me in 1993. But after examining the research on marijuana's effects, he said, "I realized that I had been brainwashed, like everybody else in the country." In his book, he methodically debunked many scary claims about pot, including fears that it caused crime, sexual excess, psychosis, brain damage, physical dependence, and addiction to other drugs.

The following year, the Nixon-appointed National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse reached broadly similar conclusions: that the dangers of pot had been greatly exaggerated and could not justify punitive treatment of its users. The commission introduced the concept of decriminalization, which the newly formed National Organization for the Repeal of Marijuana Laws (NORML)—which early on replaced repeal with reform in its name—soon adopted as a goal. At a time when some 600,000 people were being arrested each year on marijuana charges, most for simple possession, the strategy had broad appeal. Liberals were concerned about the injustice of sending college students to jail for carrying a joint or two. Conservatives worried about the mass alienation and disrespect for the law that the policy was breeding.

In 1973 Oregon became the first state to "decriminalize" marijuana, making possession of less than an ounce a civil offense punishable by a maximum fine of $100. By the end of the decade, 11 states had decriminalized possession, a policy endorsed by President Jimmy Carter, the American Bar Association, the American Medical Association, and the National Council of Churches. Every other state had reduced the penalty for simple possession, nearly all of them changing the offense from a felony to a misdemeanor. Most allowed conditional discharge, without a criminal record.

That was the context of Grinspoon's optimism in 1977, when he published an updated edition of Marihuana Reconsidered. But as he noted at the time, decriminalization, while a clear improvement, was not an adequate solution, and it was inherently unstable. "As long as marihuana use and especially marihuana traffic remain in this peculiar position neither within nor outside the law, demands for a consistent policy would remain strong," he wrote. "We would have to ask ourselves why, if using marihuana is relatively harmless, selling it is a felony; then we would have to decide whether to return to honest prohibition or move on to legalization."

Although it took longer than Grinspoon expected, Americans eventually grappled with that conundrum and resolved it in favor of legalization, which two-thirds of respondents supported in the most recent Gallup poll. Given the current climate of opinion, it is easy to overlook the courage and perseverance it took to calmly, graciously, and persistently advocate a cause that remained broadly unpopular until the last decade or so.

But Grinspoon, who served for many years on NORML's board of directors, did more than that. In his 1993 book Marihuana: The Forbidden Medicine, co-authored by James B. Bakalar, he made the case that cannabis—which was a common ingredient in patent medicines during the 19th century, when it was extravagantly promoted as a cure for a wide range of maladies, including coughs, colds, corns, cholera, and consumption—actually had scientifically verifiable medical potential. That was three years before California became the first state to allow medical use of marijuana, a policy that was eventually adopted by 32 other states.

The significance of that development is hard to overstate, because it not only highlighted the potential benefits of a long-demonized plant but focused attention on its side effects, an obvious concern when medically frail people use it for symptom relief. The hazards of marijuana, in turned out, compared quite favorably to those of many widely prescribed pharmaceuticals. And in states like California, where loose rules allowed pretty much anyone to legally obtain marijuana as long as they had a doctor's note, permitting medical use became a test for broader legalization. The sky did not fall—a point recognized by the voters who eventually approved tolerance of recreational use in California and elsewhere.

Grinspoon's position on marijuana's therapeutic potential was ultimately endorsed, to at least some extent, by such scientific authorities as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Two years ago, the FDA, which had approved a synthetic version of THC as a treatment for AIDS wasting syndrome and the side effects of cancer chemotherapy in the 1980s, authorized the sale of Epidiolex, the first cannabis-derived medication to be approved by the U.S. government, as a treatment for two rare kinds of epilepsy.

Grinspoon's advocacy was not limited to marijuana. In their 1979 book Psychedelic Drugs Reconsidered, he and Bakalar gave that class of psychoactive substances, which had long terrified politicians and the general public, the same sort of demystifying treatment that Grinspoon had applied to marijuana eight years earlier. As with marijuana, government officials have acknowledged at least some of the truth Grinspoon was telling. In 2018, the same year it approved Epidiolex, the FDA recognized psilocybin as a "breakthrough therapy" for depression, signaling that it might be approved as a prescription drug sometime in the next few years. Meanwhile, state and local activists are pushing for legal tolerance of nonmedical psilocybin use. They scored their first victory in Denver last year.

It is safe to say that Americans, most of whom favor the legalization of psychedelics as psychotherapeutic catalysts, are much calmer about those drugs than they were in the 1960s and '70s. That sort of reevaluation does not come out of thin air. It is a function of the arguments and evidence marshaled by pioneering public intellectuals like Grinspoon.

Grinspoon did not simply argue that the government should allow the use of drugs that prove to be "relatively harmless," as he described marijuana in the 1970s. In the 1984 book Drug Control in a Free Society, he and Bakalar delved into the deeper issues raised by politicians' attempts to enforce their pharmacological prejudices.

Starting with John Stuart Mill's On Liberty and with nods toward libertarians such as Thomas Szasz and Robert Nozick, Grinspoon and Bakalar thoughtfully challenged the case for paternalistic drug policies; questioned the conventional understanding of addiction; noted how a sweeping conception of public health becomes a license for all manner of meddling in personal choices; highlighted the arbitrary legal distinction between alcohol and other drugs; and insisted that the pleasure people get from drugs should count for something in any calculus of prohibition's cost and benefits. It is a slim, wisdom-packed volume that is still relevant 36 years later.

Americans have mostly accepted Grinspoon's position on marijuana, and they may be coming around on psychedelics as well. I am less hopeful that they will ever think logically, consistently, and systematically about drug policy in general. But if they do, it will thanks to dogged dissidents like Grinspoon.

Show Comments (14)