When a London man discovered the front left-side bumper of his Toyota RAV4 torn off and the headlight partially dismantled not once but twice in three months last year, he suspected the acts were senseless vandalism. When the vehicle went missing a few days after the second incident, and a neighbor found their Toyota Land Cruiser gone shortly afterward, he discovered they were part of a new and sophisticated technique for performing keyless thefts.

It just so happened that the owner, Ian Tabor, is a cybersecurity researcher specializing in automobiles. While investigating how his RAV4 was taken, he stumbled on a new technique called CAN injection attacks.

The case of the malfunctioning CAN

Tabor began by poring over the “MyT” telematics system that Toyota uses to track vehicle anomalies known as DTCs (Diagnostic Trouble Codes). It turned out his vehicle had recorded many DTCs around the time of the theft.

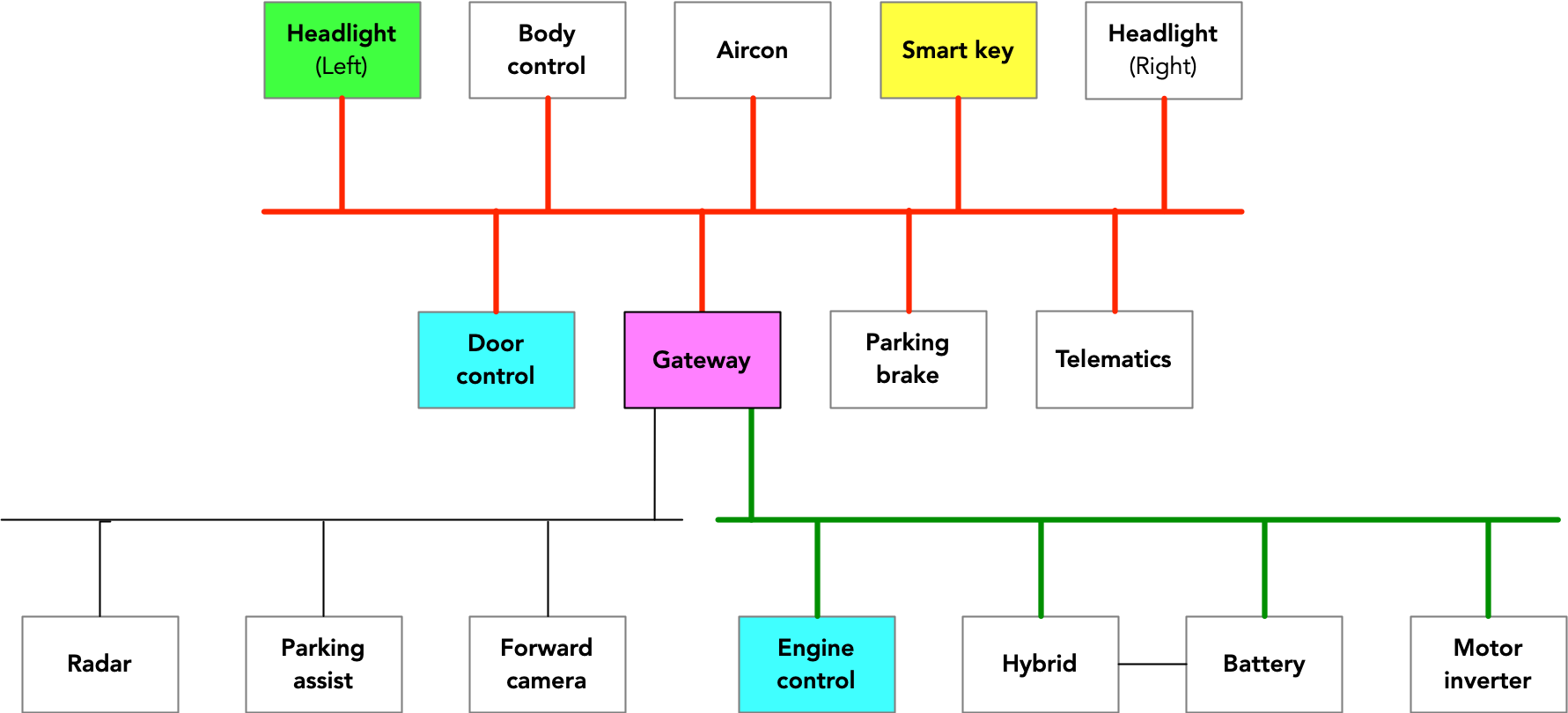

The error codes showed that communication had been lost between the RAV4’s CAN—short for Controller Area Network—and the headlight’s Electronic Control Unit. These ECUs, as they’re abbreviated, are found in virtually all modern vehicles and are used to control a myriad of functions, including wipers, brakes, individual lights, and the engine. Besides controlling the components, ECUs send status messages over the CAN to keep other ECUs apprised of current conditions.

This diagram maps out the CAN topology for the RAV4:

The DTCs showing that the RAV4’s left headlight lost contact with the CAN wasn’t particularly surprising, considering that the crooks had torn off the cables that connected it. More telling was the failure at the same time of many other ECUs, including those for the front cameras and the hybrid engine control. Taken together, these failures suggested not that the ECUs had failed but rather that the CAN bus had malfunctioned. That sent Tabor searching for an explanation.

[chalk it up there with, "in the unlikely event there ever is a positive leap second, i don't want to be on an airplane when it's applied" -- like, i know i'm being paranoid here. however, given what i've just read...]

In anything, keyless entry is a net drain on my time. I never forget the key to my Miata, but I constantly go to get in the Camry only to realize that I left the key in a different jacket.