- News

- India News

- Burning bright alright, but will we let the tigers live?

Trending

This story is from April 1, 2023

Burning bright alright, but will we let the tigers live?

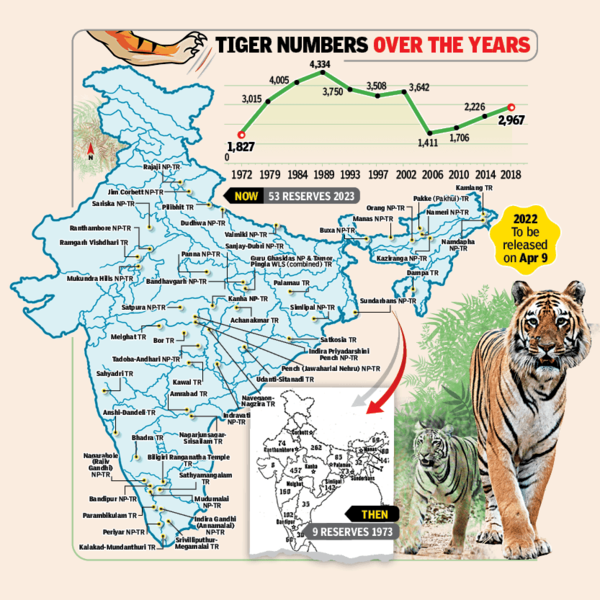

Project Tiger completes 50 years today. Launched in 1973, the plan was to conserve and protect the species as the numbers had reduced due to hunting. To a large extent it is a success story for India to tell the world. TOI looks at the years gone by and what lies ahead. Political will, committees delivered Project Tiger, averted cat’s extinction

In November 1998, the government and conservationists celebrated the 25th anniversary of Project Tiger, claiming tiger numbers had stabilised and all was well.

From 40,000 Royal Bengal tigers at the start of 19th century to a mere 1,800 in the ’70s. Reason enough for panic buttons to be hit.

Worldwide concern too reached a flashpoint. In 1969, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) general assembly in Delhi heard the assessment by IFS officer KS Sankhala, and called for a moratorium on tiger killings and protection for the species.

Then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi expressed full support to save tigers from extinction and India banned tiger hunting for five years. But the international community was not convinced. WWF planned a massive fund raising campaign. Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands and others put in a word, and Gandhi set up a task force chaired by Karan Singh, a well-known conservationist and MP. Its report on September 7, 1972, was the blueprint for India’s tiger conservation programme — Project Tiger.

But the international community was not convinced. WWF planned a massive fund raising campaign. Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands and others put in a word, and Gandhi set up a task force chaired by Karan Singh, a well-known conservationist and MP. Its report on September 7, 1972, was the blueprint for India’s tiger conservation programme — Project Tiger.

Gandhi formally launching it on April 1, 1973, from the Jim Corbett National Park. First conceived for only six years — April 1973 to March 1979 — its objective was to ensure the maintenance of a viable population of tigers in India and to preserve, for all times, such areas as part of our national heritage for the benefit, and education of future generations.

This has grown to 53 tiger reserves today and covers an area of over 75,000 sqkm, equivalent to the area of Assam, harbouring a population of 2,967 tigers as per the AITE-2018, spread over 18 tiger-range states. Over the 50 years, the funding has improved to nearly Rs 500 crore today.

The turning point in India’s tiger conservation programme came in the 1990s when problems erupted and were managed, but not really solved. This was also a period, like the early 1970s, when international NGOs were pushing policy in the country.

A critical review of Project Tiger, carried out in 1993 by the MoEF, acknowledged the problems.

“All in all, Project Tiger faces a new set of problems. It saved the tiger from extinction in the nick of time, but over 20 years it is clear that expanding human population, a new way of life based on alien models, and the resultant effect on natural resources have created fresh problems for the tiger. Militancy and poaching only add fuel to the fire. This is a serious and critical moment in the history of tiger conservation.”

In 1994, a parliamentary committee on science, technology, environment, and forests recommended making the programme more meaningful and result oriented. The committee felt this was necessary as the tiger population had registered a decline, poaching assumed menacing proportions and tiger habitats seemed to have shrunk in area.

So came another high-powered committee in 1996 headed by JJ Dutta, ex-PCCF of MP. The panel recommended looking beyond identifying corridors.

In November 1998, the government and conservationists celebrated the 25th anniversary of Project Tiger, claiming tiger numbers had stabilised and all was well.

The celebrations were short-lived as poachers and tiger body parts traders led by Sansarchand wiped out the entire tiger population of the Sariska Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan. By 2004, with no tigers left there, Project Tiger was forced to set up a five-member tiger task force (TTF) on April 19, 2005, under Sunita Narain, director, Centre for Science and Environment.

This led to formation of National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) in 2006 with scientific management and evaluation of tiger reserves.

In 2006, the tiger population was estimated at 1,411, much lower than the earlier estimates. This brought about major changes in tiger conservation policy, legislation, and management. Since then the NTCA conducts a national assessment of the ‘status of tigers, co-predators, prey and habitat’ every four years.

The stress was now on village relocation from core/critical habitats, and enhanced protection by Special Tiger Protection Force. “Soon, tiger population estimates went up to 1,706 in 2010,” said NTCA officials.

The 2014 and 2018 tiger assessments were the most accurate, covering 3,81,400 sqkm of forested habitats. NTCA officials believe this is the world’s largest effort invested in any wildlife survey to date. “A total of 2,461 individual tigers were photo-captured. The overall tiger population in India was estimated at 2,967,” they said. Though Project Tiger’s (now NTCA) model has evolved, tiger conservation has lacked broad-based political support. Experts hope for the better in the next 50 years.

(Source: ‘Indira Gandhi: A life in nature’, by Jairam Ramesh)

Worldwide concern too reached a flashpoint. In 1969, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) general assembly in Delhi heard the assessment by IFS officer KS Sankhala, and called for a moratorium on tiger killings and protection for the species.

Then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi expressed full support to save tigers from extinction and India banned tiger hunting for five years.

Gandhi formally launching it on April 1, 1973, from the Jim Corbett National Park. First conceived for only six years — April 1973 to March 1979 — its objective was to ensure the maintenance of a viable population of tigers in India and to preserve, for all times, such areas as part of our national heritage for the benefit, and education of future generations.

The Rs 4-crore Project Tiger, including Rs 22 lakh in foreign exchange, started with nine viable tiger reserves representing different ecosystems where the tiger could be protected in perpetuity. These were Manas (Assam),Palamau (Jharkhand), Simlipal (Odisha), Corbett (Uttarakhand), Ranthambore (Rajasthan) Kanha (MP), Melghat (Maharashtra), Bandipur (Karnataka) and Sundarbans (West Bengal), in an area of 9,115 sqkm.

This has grown to 53 tiger reserves today and covers an area of over 75,000 sqkm, equivalent to the area of Assam, harbouring a population of 2,967 tigers as per the AITE-2018, spread over 18 tiger-range states. Over the 50 years, the funding has improved to nearly Rs 500 crore today.

The turning point in India’s tiger conservation programme came in the 1990s when problems erupted and were managed, but not really solved. This was also a period, like the early 1970s, when international NGOs were pushing policy in the country.

A critical review of Project Tiger, carried out in 1993 by the MoEF, acknowledged the problems.

“All in all, Project Tiger faces a new set of problems. It saved the tiger from extinction in the nick of time, but over 20 years it is clear that expanding human population, a new way of life based on alien models, and the resultant effect on natural resources have created fresh problems for the tiger. Militancy and poaching only add fuel to the fire. This is a serious and critical moment in the history of tiger conservation.”

In 1994, a parliamentary committee on science, technology, environment, and forests recommended making the programme more meaningful and result oriented. The committee felt this was necessary as the tiger population had registered a decline, poaching assumed menacing proportions and tiger habitats seemed to have shrunk in area.

So came another high-powered committee in 1996 headed by JJ Dutta, ex-PCCF of MP. The panel recommended looking beyond identifying corridors.

In November 1998, the government and conservationists celebrated the 25th anniversary of Project Tiger, claiming tiger numbers had stabilised and all was well.

The celebrations were short-lived as poachers and tiger body parts traders led by Sansarchand wiped out the entire tiger population of the Sariska Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan. By 2004, with no tigers left there, Project Tiger was forced to set up a five-member tiger task force (TTF) on April 19, 2005, under Sunita Narain, director, Centre for Science and Environment.

This led to formation of National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) in 2006 with scientific management and evaluation of tiger reserves.

In 2006, the tiger population was estimated at 1,411, much lower than the earlier estimates. This brought about major changes in tiger conservation policy, legislation, and management. Since then the NTCA conducts a national assessment of the ‘status of tigers, co-predators, prey and habitat’ every four years.

The stress was now on village relocation from core/critical habitats, and enhanced protection by Special Tiger Protection Force. “Soon, tiger population estimates went up to 1,706 in 2010,” said NTCA officials.

“The project is a comment on a long neglect of our environment as well as our new-found, but most welcome concern for saving one of nature’s most magnificent endowments for posterity. But the tiger cannot be preserved in isolation, it is at the apex of a large and complex biotope. Its habitat by human intrusion, commercial forestry, and cattle grazing must first be made inviolate. Forestry practices designed to squeeze the last rupee out of a jungle must be radically reoriented at least within national parks and sanctuaries and predominantly in the tiger reserves. The narrow outlook of the accountant must give way to a wider vision of the recreational, educational and ecological value of totally undisturbed areas of wilderness

Indira Gandhi’s message on Project Tiger’s launch on April 1, 1973

The 2014 and 2018 tiger assessments were the most accurate, covering 3,81,400 sqkm of forested habitats. NTCA officials believe this is the world’s largest effort invested in any wildlife survey to date. “A total of 2,461 individual tigers were photo-captured. The overall tiger population in India was estimated at 2,967,” they said. Though Project Tiger’s (now NTCA) model has evolved, tiger conservation has lacked broad-based political support. Experts hope for the better in the next 50 years.

(Source: ‘Indira Gandhi: A life in nature’, by Jairam Ramesh)

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA