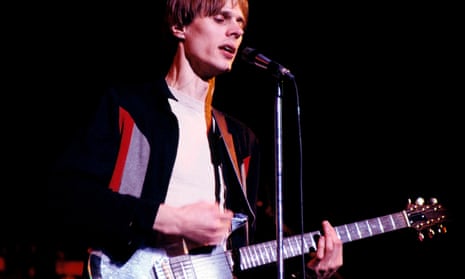

As a guitarist, Tom Verlaine was a player whose unhinged vibrato, sweeping volume swells, splintered harmonics, cool noir ambience, and, most crucially, his discursively elegant lyricism, emerged in the mid-1970s as a moody antidote to the macho guitar heroism of that era. And for a certain kind of guitarist – like me – he was a fountainhead for an entirely new era to come.

I struggle to think of a player before Verlaine who synthesised the same range of influences – early Stones stomp and sneer, angular Ayler-isms, sensuous dreamscapes, extended improvisation, and spaghetti western twang – while dispensing entirely with the then-dominant white blues cliches. Sure, there were antecedents – John Cipollina, Roger McGuinn, and Jerry Garcia, for example, and I hear the wiggy high-wire tension of Mike Bloomfield’s mid-60s work in there as much as anything. But Verlaine’s sound with Television defined the archetype of the avant-rock guitarist, one that would become as much a template for the sound and feel of 80s guitar music as the contemporary innovations of Eno, George Clinton, Kraftwerk or Nile Rogers were in their own idioms.

The early records of bands such as U2 and REM are unfathomable without Verlaine’s influence – Television basically invented the Athens band’s IRS years in a single song, Days from 1978’s Adventure – and a whole slew of artists, including Patti Smith, Echo & the Bunnymen, the Church, Siouxsie and the Banshees and many more took Verlaine’s innovations to a wider audience. In short, the arc of what was once called punk, then new wave, then college rock, then alternative rock, then most recently indie rock can be traced, musically and aesthetically, directly to Verlaine’s fretboard. Even the popularity of arguably the most iconic and ubiquitous guitars of the last 30 years – the Fender Jazzmaster and Fender Jaguar – was kicked off by Verlaine’s prominent use of models that were unfashionable at the time.

For me, any discussion of Verlaine’s brilliance starts with Television’s 1978 version of Little Johnny Jewel from their live compilation The Blow-Up: simply the most sublime 15 minutes of recorded guitar playing I have ever known. You could think of it as the A Love Supreme of punk, with John Coltrane collaborator Jimmy Garrison’s bobbing four-note bass line replaced by a similarly hypnotic six-note figure over which Verlaine roams free, weaving glorious, careening, dynamic patterns in the air. It features some of his most fiery excursions, full of sprawling harmonic feedback, tremolo arm abuse and (barely) controlled noise over drummer Billy Ficca’s syncopated funk; bassist Fred Smith and Verlaine’s guitar partner Richard Lloyd hold on to that riff for their lives like rodeo cowboys on wild horses. It lays the foundation for the work of Thurston Moore, Lee Ranaldo, and Kim Gordon in Sonic Youth, J Mascis in Dinosaur Jr and subsequent generations of guitar antiheroes. Rarely has rock music sounded and felt so transcendent.

Some of his brilliance has dipped beneath the radar. Verlaine’s 1992 instrumental album Warm and Cool is an understated masterwork, featuring beautiful, narrative, folk-like melodies as well as the most explicit free jazz-influenced statements in his discography. Each note in the slowly unfolding melody of Spiritual reveals itself like a discrete shooting star, with a mysterious raga-like internal complexity. (A highlight of Warm and Cool, the track expands exponentially into a gorgeous 15-minute fantasia on a widely circulated unofficial live recording performed on 29 October 1998 at the Bowery Ballroom in New York City.)

Verlaine’s style was guitar playing beyond technique. You could call it virtuosic, but that would miss the point. To improvise at his level requires maximum presence. He would often incorporate long, odd intervals by hitting an open string and hammering on to another note much higher up the neck, or create rattling, dissonant timbres by strumming multiple strings extremely fast while dragging dissonant chords around the neck chromatically. The droning bell-like single note with which he opens his extended break on Marquee Moon, the song with which he will forever be identified, is one of the most mysterious, sensual, and compelling introductory phrases in rock soloing.

As a teen, I could figure out many rock players by ear but was bewildered by the playing on Television records. When I later had the privilege of studying with Richard Lloyd, I became able to understand from a technical standpoint why that was: on those records, he and especially Verlaine rarely use the accessible pentatonic scales common to most blues-based music and instead favour variations on major/minor-scale modes that include more melodic filigree. The logic is more classical than Clapton.

Maybe the most punk thing about Verlaine is that he always seemed to have something to say in those extended workouts. He needed the time he took as much as Coltrane or Morton Feldman needed theirs. His was not ponderous music, full of wonder and beauty though it was. It was lean and hungry and on the hunt. Tom Verlaine’s guitar playing seemed very much alive and in the moment at all times, which is as high a compliment as I can imagine. And thankfully for us, it lives on.

after newsletter promotion