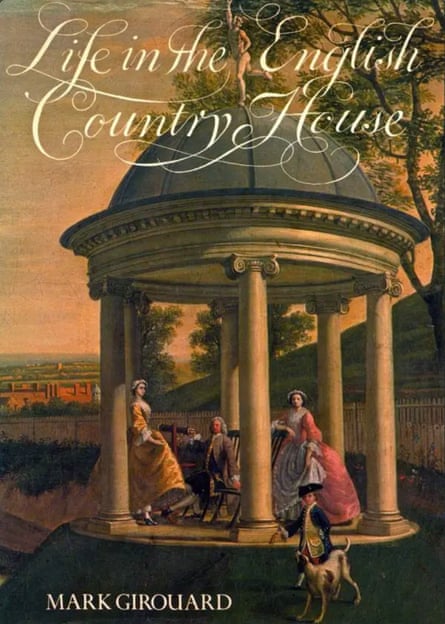

Mark Girouard, who has died aged 90, was Britain’s most readable architectural historian, a great authority on Elizabethan and Victorian architecture whose extensive writings used the study of buildings to illuminate the social life of the past. The publication of Life in the English Country House: A Social and Architectural History in 1978 captured the zeitgeist in a period when stately homes were being repurposed as sites of mass leisure. It sold more than 140,000 copies in hardback.

When Girouard started his career the study of architectural history in Britain was dominated by the German-trained Nikolaus Pevsner, for whom the discipline was essentially about tracking artistic styles through intense formal and spatial analysis. In contrast, Girouard’s books placed buildings within their cultural, social and intellectual milieu. The results were scholarly, but also immensely fun, gossipy and stylish.

Although he wrote a great deal about country houses, he found much of the fogeyish snobbery and nostalgia that often goes with the territory distasteful. Free of pomposity, puckish, self-effacing and urbane, he was much loved by all sorts of people for his kindness and sense of fun. Girouard took on a terrific range of subjects beyond country houses, writing with verve about Victorian Pubs (1975) and urban history in Cities and People: A Social and Architectural History (1985) and The English Town: A History of Urban Life (1990).

Perhaps his most moving book is The Return to Camelot: Chivalry and the English Gentleman (1981), which tracks how the cult of medieval chivalry in Edwardian England led to the gung-ho militarism that would have such disastrous effects during the first world war. His political sensibilities, which mixed the patrician and the progressive, are best reflected in Sweetness and Light: The “Queen Anne” Movement 1860-1900 (1977), a study of the way the late Victorian intellectual establishment used a cheerful and undogmatic architecture of swags and cherubs to further a paternalist liberal social agenda.

Born at his family’s home on Upper Berkeley Street, Mayfair, in central London, Mark was the son of Blanche (nee Beresford), a novelist and the eldest daughter of the sixth Marquess of Waterford, and her husband, Richard Girouard, a stockbroker. His mother died in a car crash when he was eight, during his first term boarding at Avisford preparatory school, West Sussex, and he was not allowed to attend the funeral.

The second world war had started, and his father was in the army. His extended family networks kicked in, and his first experiences of country houses came through holidays spent in Britain and Ireland, at establishments including Chatsworth and Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, with his great-aunt the Duchess of Devonshire.

He remembered Ampleforth college, North Yorkshire, less for the Catholic education he received there and more for walking to surrounding buildings such as Rievaulx Abbey and Castle Howard. He was known at school as Coconut, as his hair was “wiry, brown and even then far from abundant”. His national service was spent with the Nigeria Regiment of the Royal West African Frontier Force. He was not a natural soldier and clumsily stabbed himself in the face trying to unfix a bayonet.

He regretted reading classics and philosophy at Christ Church, Oxford, but loved skating on the lake at the nearby Blenheim Palace and sharing digs with Thomas Pakenham, the future historian and Earl of Longford, in Caudwell’s Castle on Folly Bridge Island in south Oxford. They went church-crawling in a battered old black taxi, until Girouard crashed it into a lorry.

His time at Hardwick Hall inaugurated a lifelong interest in Elizabethan and Jacobean architecture. Girouard’s PhD (1957) from the Courtauld Institute in London was published in an expanded form as Robert Smythson and the Architecture of the Elizabethan Era (1966). This was a major piece of archival detective work, establishing Robert Smythson, previously seen as an obscure master builder, as the presiding genius of the so-called prodigy houses at Longleat, Wollaton, Hardwick and Bolsover.

From 1958 to 1966 Girouard worked as a staff writer at Country Life, which gave him the opportunity to “get paid for the highly enjoyable work of digging and delving, and with luck finding neglected rolls of architectural drawings under country house billiard tables, or boxes of mildewed building accounts in their attics”. He would normally be put up as a guest by the owners, so when the Earl of Carnarvon at Highclere Castle, Hampshire, made him eat alone, separately from both servants and nobility, he was wryly put out.

While at Country Life he developed a specialism in the then highly unfashionable subject of Victorian architecture, which would result in The Victorian Country House (1971), a book notable for its focus on the technological and planning aspect of the houses, including their plumbing, heating and ventilation.

Girouard’s interest in Victorian architecture brought him into touch with the nascent conservation movement, and he was a founding member and leading light of the Victorian Society. From 1962, when Harold Macmillan signed off the demolition of the Euston Arch outside the station in central London, he refused to vote Conservative ever again.

In the 1970s, when a group of friends came up with the idea of protecting at-risk buildings by buying them, repairing them and selling them on, it was Girouard who suggested saving the Georgian houses of Spitalfields, in the East End of London, and he became the first chairman of the Spitalfields Trust. He started his chairmanship with a piece of theatrical direct action, and was one of a group who squatted for seven weeks in two condemned 18th-century weaver’s houses on Elder Street to prevent demolition by British Land. They had dinner parties among the dereliction and slept on the floor, while the bulldozers waited outside.

The poet John Betjeman, who teasingly and incorrectly referred to Girouard as his “dearest little godson”, exaggerated that he “never said a word” on the multiple heritage committees he had a role in: Girouard was a steely and committed activist for the buildings he loved. His writing on Tyntesfield, a Victorian gothic revival house near Bristol, was instrumental in saving it and its collections for the nation in 2002.

In 1966 he left Country Life to train as an architect at the Bartlett school of architecture, part of University College London, as a mature student. Although he qualified he was disillusioned by the experience. He designed a single building, the Edith Neville primary school in Somers Town, north London (1971); it has since been demolished.

Many architectural historians of his generation displayed a virulent anti-modernism, but he did not share this, enjoying the company of architects whom he got to know while working for the Architectural Review during the 1970s. He defended Denys Lasdun’s brutalist National Theatre against the Prince of Wales’s attacks. He also admired James Stirling, especially the Leicester Engineering Building, which reminded him of Hardwick Hall. The biography Big Jim: The Life and Work of James Stirling (1998) was fantastically indiscreet and very funny, but, to his regret, hurt Stirling’s widow, Mary.

While at the Bartlett he met Dorothy Dorf, and they married in 1970. Dorothy was a painter, and also designed many of his books. They separated in the 90s. Their daughter, Blanche, a writer, was born in 1976, and survives him.

Friendships (2017) recorded Girouard’s great capacity for companionship, centred on pubs, dinner parties in Notting Hill, and exploring buildings. He remained intellectually active to the end. In 1956 the medievalist John Harvey had suggested Girouard was the only possible person to write a biographical dictionary of Elizabethan and Jacobean architecture. This was finally published in 2021 as A Biographical Dictionary of English Architecture 1540-1640, to great acclaim.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion