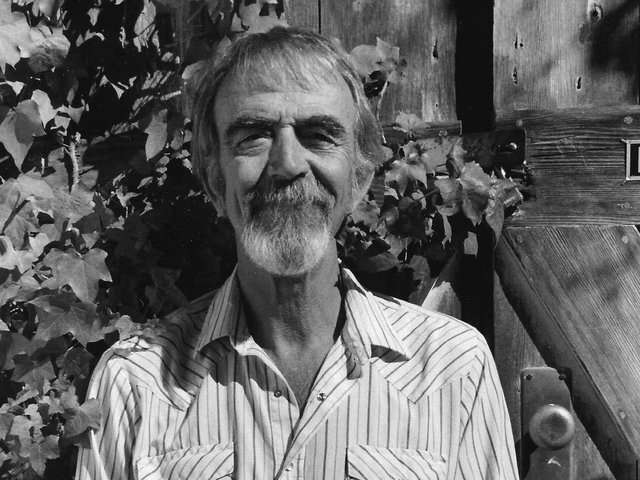

The Ojibwe artist Jim Denomie died at age 66 of cancer on 1 March in Franconia, Minnesota, surrounded by his family. His wife Diane Wilson wrote on Facebook of Denomie’s “kind, gentle, funny nature”, and “his passion for art, and his deep commitment to family”.

At the time of his death, Denomie was preparing for a solo exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) that is scheduled for 2023. “The exhibition will be exploring the troubadour-like approach that Jim had towards art,” says curator Nicole Soukup, noting that Denomie often listened to music, like Bob Dylan, when he painted. According to Soukup, Denomie was also inspired by children’s art and 16th-century painter Hieronymus Bosch.

In addition to preparing for the upcoming Mia exhibition, Denomie had since 2019 travelled to São Paulo, Vienna and Mexico City for shows. Institutions including the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the Westphalian Museum of Natural History, in Munster, Germany, and the Denver Art Museum had acquired his work.

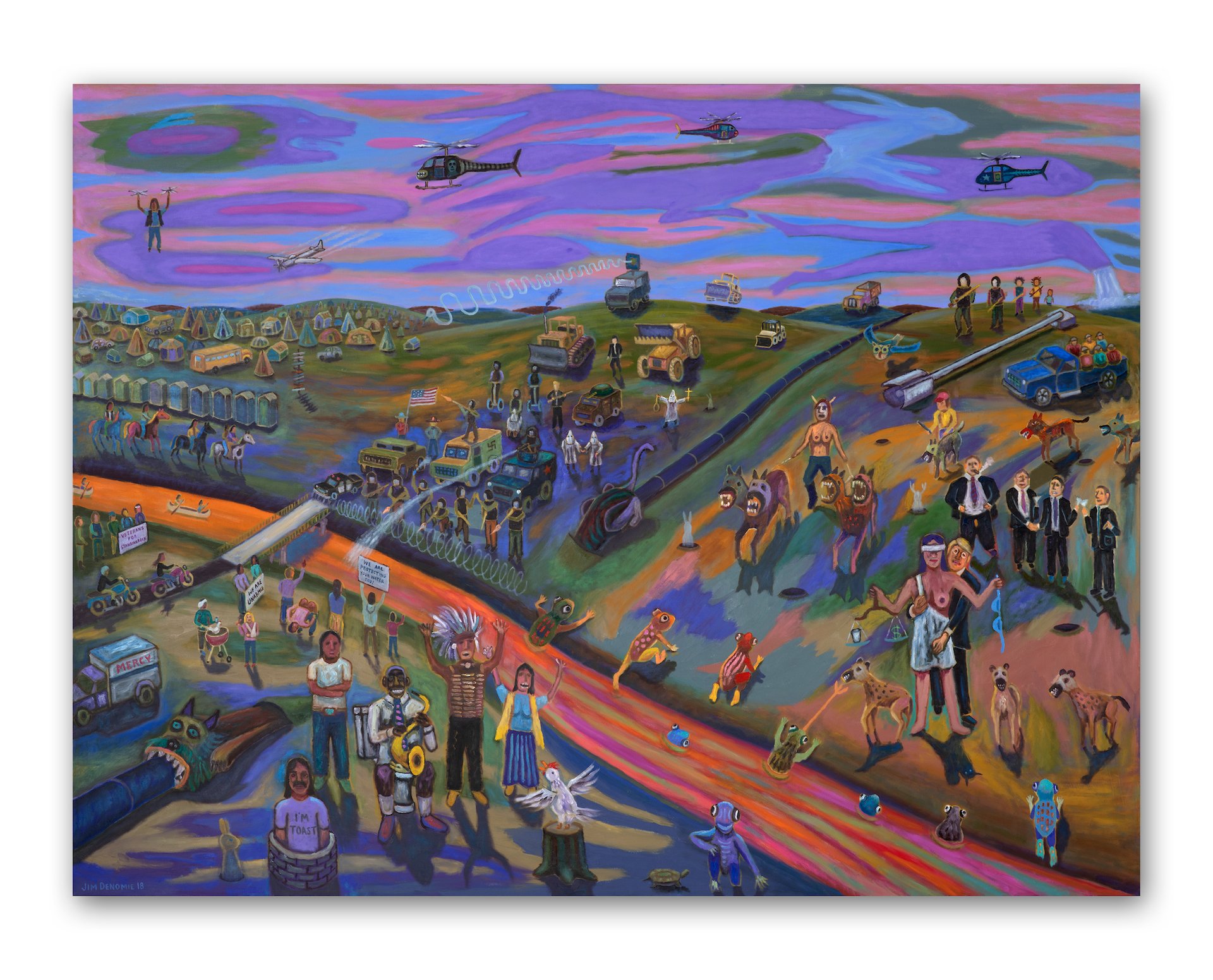

Jim Denomie, Standing Rock 2016, 2018 © Jim Denomie

Estate and Bockley Gallery

Candice Hopkins, executive director of Forge Project in New York, places Denomie’s work in dialogue with Indigenous artists like Cree painter Kent Monkman and the late Luiseño, Ipai and Mexican American performance artist James Luna. “I think that his content is very much of the moment of what a lot of his younger peers are making work about: a culturally specific critique of not just the world, but making our histories known,” she says.

A sophisticated colourist with an acerbic sense of humour, Denomie also conveyed a sense of deep spiritual mysticism through his work.

“Jim kept odd hours,” says poet and curator Heid E. Erdrich. “That’s one of the reasons he painted rabbits. He’d look out at the rabbits on the snow in the yard at night and think of them as little guardians of the night.”

Though best known as a painter, Denomie recently completed a sculptural piece, Totem, Animal Spirts (2021), made of a log worked into three faces, the topmost having eyes on both sides. “It was something he kept a little bit quieter,” Soukup says of his sculpture practice.

Jim Denomie, Totem, Animal Spirits, 2021, collection of Forge Projects © Jim Denomie Estate and Bockley Gallery

Born in 1955 on the Lac Courte Oreille reservation in Wisconsin, Denomie moved to Chicago as a child because of the Indian Relocation Act, then grew up in Minneapolis. A Lac Court Oreilles Band of Ojibwe member, he became interested in reclaiming Native American culture and spirituality in his 30s. At 35, he participated in a naming ceremony.

He graduated with a BFA from the University of Minnesota in 1995 and had his first solo exhibition at Two Rivers Gallery in Minneapolis that year. Soon, he became an integral figure in the local scene.

“Jim was a community builder,” Erdrich says. “He mentored and encouraged Andrea Carlson, Dyani White Hawk, Maggie Thompson—a number of artists who've gone on to have terrific careers.”

“I’ve always looked up to him,” Carlson says. “He would probably see us as colleagues.”

When she saw him in Grand Marais, Minnesota, last autumn, Carlson says Denomie told her about a new painting series he was working on depicting the 38 Dakota executed in Mankato in 1862—the largest mass execution in US history. Several weeks ago, Carlson heard from Denomie with the news about his cancer. “He was like, ‘I just want enough time on this planet to finish this work,’” Carlson says. “He didn’t get that time.”

Denomie and Carlson were featured together in Mia’s Minnesota Artist Exhibition Project in 2007, where Denomie’s contributions included expressive paintings he would make in one day. “It started the practice of getting into the studio and thinking and working every single day,” says Soukup. “It was transformational for him.”

Besides the ghostly Rugged Indian portrait series, gallerist Todd Bockley was drawn to a large-scale painting called Attack on Fort Snelling Bar and Grill (2007), which renders Fort Snelling in St. Paul, Minnesota as a White Castle fast food restaurant. “He’s got the ability to use this paintbrush almost as if it’s a weapon,” Bockley says.

Jim Denomie, Attack on Fort Snelling Bar and Grill, 2007, collection of the

Weisman Art Museum © Jim Denomie Estate and Bockley Gallery

In 2017, Denomie was awarded a residency at the Joan Mitchell Center in New Orleans. “It’s really there where he realised how he reacted to space and place and how the landscape informed what he was doing,” Soukup says.

Another important moment in Denomie’s practice came during the Standing Rock movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016-17. “There’s a real urgency in everything post-Standing Rock,” Soukup says, noting Mia will acquire his canvas Standing Rock 2016 (2018). “I think it is one of the most important paintings of our time.”

Jill Ahlberg Yohe, Mia’s associate curator of Native American Art, writes over email that Denomie painted the “raw realities of America”. She adds: “His generosity, kindness, and support of fellow artists, art enthusiasts and art professionals will continue to inspire us all.”