Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Going paperless in a metal fabrication job shop

Texas fabricator cuts out 'information waste,' builds off tools and technology it already had

- By Tim Heston

- January 12, 2022

- Article

- Manufacturing Software

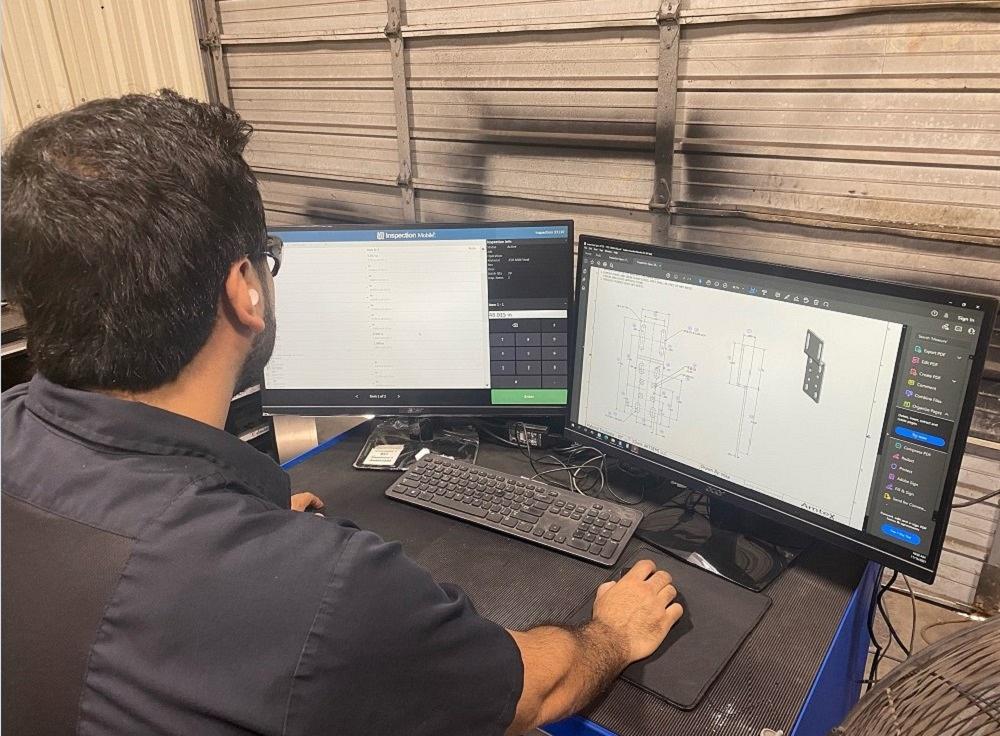

Controls in Amtex’s press brake department show a 3D model bending simulation as well as a PDF of the job’s original drawing. Images: Amtex Precision Fabrication

The late Dick Kallage, a longtime industry consultant who worked closely with the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association Intl. (FMA), talked at length about what he called “information waste.” Most metal fabrication in North America occurs in job shops—places with just a handful of employees who manage machinery and, most impressive of all, thousands of different orders every year.

Kallage used to joke that fabricators would analyze the minutiae of machine production, aiming to cut or weld a few more inches per minute. Such gains weren’t anything to sniff at, but the scrutiny did seem a bit quixotic when he found the same shops processing incorrect orders (spurring customer returns or rework), or when people throughout the business spent hours looking for a certain drawing, job jacket, or quote—especially if someone had to handle work started by someone who called in sick or was on vacation. Unlike machine uptime, problems associated with information waste are rarely measured, so they’re rarely noticed.

Several years ago, managers at Amtex Precision Fabrication, a 23-employee precision sheet metal job shop in Manvel, Texas, did notice that information waste, and they did something about it. They went paperless.

Recognizing the Problem

“The production manager was spending about four hours a week just reprinting the paperwork that was lost on the shop floor. We had drawings that would go missing. Job travelers were missing, as was other paperwork with job-related information.

“And when we reprinted them, the originals were out there somewhere, so once a week we’d end up doing cleanups, and we’d do deep cleanings once a month. We’d sometimes find big piles of job packets, and we would have to wonder, is this job active? Is it not active? We just spent a lot of wasted time dealing with the mess and clutter.”

That was Adrian Wagner, Amtex’s vice president of manufacturing, who added that time spent finding paperwork really just scratched the surface of the problem. When managers dug deeper, they found more inefficiencies, even for jobs that weren’t lost at all. When customers would call about a part revision, the production manager would have to walk to the floor and find every printed piece of paper connected to the job to ensure it was up to date.

“We spent so much time ensuring all the paperwork everywhere in the shop was correct,” Wagner said. “Ultimately, we’d miss something at some point, and then we’d have a bad part.” The rework ensued and costs mounted.

The potential for waste didn’t end there. A welder might have missed a detail on a drawing printout. At best, he’d have to stop, get out his reading glasses, and comb through the paperwork to ensure he caught every detail that he missed at first glance. At worst, he’d miss a detail and produce a bad part. That led to more rework and more costs.

Then came the paperwork hunt every time a customer called to reorder an old job. Sure, some job information was in digital format, like old customer emails and initial quote information, but most of the production information was all filled out by hand. After a job shipped, the shop stored the job information for five years in boxes—not by job number, but by ship date. “If we needed to go back and look at anything, we had to go through multiple boxes,” Wagner said.

Managers also observed the time it took for people to actually find the information they needed, using a job packet that arrived at the right workstation at the right time with the right revision. Even in these “ideal” cases, employees spent many minutes paging through drawings, especially if the job involved an assembly with many components. “Those drawing packets could get pretty thick,” Wagner said. “They would pick through all that paper, leave a stack by the workstation, and this is Texas—in the summer, everyone has a fan blowing. You can guess what happened next.”

A Pragmatic Approach

Amtex managers knew things had to change, but they also knew a complete overhaul would be overkill. They had all the basic tools they needed to go paperless: a companywide server, an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system (in Amtex’s case, JobBOSS), and the ability to export documents to PDF format. They also knew they didn’t want to change to a paperless workflow overnight. Instead, they’d implement the workflow in phases, catch problems early on, correct them, keep paper backups for a trial period, then methodically spread complete paperless workflow throughout the shop.

What they needed next was a good place to start. They chose the quoting department, not only because personnel there already had computers at their desks, but also because the quoting process itself acts as the headwater feeding a river of information that flows through the whole organization. Get quoting wrong, and the information waste snowballs downstream.

1. Implement a paperless workflow in quoting. “The first thing we did is give everyone there two monitors,” Wagner said. “They needed to look at the client files and the ERP at the same time, and it’s too tedious to go back and forth.”

They created folders on the server that would hold everything connected to a particular quote, including customer drawings and information from outside service providers. Once they completed the quote in JobBOSS, they’d export the document as a PDF, accessible whenever it moved forward toward becoming an order, be it tomorrow or in six months. Sure, prices could change depending on when the customer decided to move forward with an order, but the information was there on the server, accessible to anyone.

Managers allowed time for questions to trickle in. The more they experimented with going paperless, the more previously unforeseen scenarios came to the fore. Some customers, for instance, have material certs and other documents—where should they be stored? “We then found that we needed another subfolder for clients,” Wagner explained, “and we called it ‘Client Maintenance Documents.’”

2. Remove paper from the rest of the office. “Once we had quoting nailed down and perfected, we started putting anything we made previously on paper into digital file folders, so we could eliminate file cabinets,” Wagner said. This included files dedicated to past and present employees. Old client drawings went into their own folder, as well as tax certifications and material test reports.

They decided to keep paper copies of certain documents for a certain number of years. But as the office’s digital transition progressed, more of those old files were thrown away, and the old filing cabinets became emptier and emptier.

3. Create a file structure for orders flowing to the shop floor. Once quotes became orders, they were put in the “Order” folder on the file tree, all organized by job number. The root folder would organize a block of 100 jobs. For instance, if people needed to access Job No. 10,050, they would click through the file tree to a folder labeled “10001-10100.”

Within each job folder was placed a PDF of the entire job traveler; the inspection record, including the drawing and what to inspect at each step (more on this later); as well as press brake and laser program files generated offline. “And in welding, our welders can zoom in to see the details they need to see,” Wagner said. “Paper size is no longer an issue.”

The shop made a server file tree structure that mirrored the structure in JobBOSS, with separate folders for quote processing, order processing, shop floor control, material control, labor reporting, shipping, and data collection.

Still, getting to that point took some experimentation. “When we started, the file tree structure was all over the place,” Wagner said. “As we started something new, we’d add a new folder. But within the past few months we’ve changed it to mirror the file structure in JobBOSS. It took time to migrate the digital data that we had already entered, but the effort was certainly worth it.”

4. Add and configure computer hardware in the shop. Managers also gradually purchased a dozen computers for the shop floor, enough for two workers to share each computer workstation. Unlike the high-powered stations running 3D CAD in the office, computers on the shop floor didn’t need to be high-end machines, which helped minimize costs.

5. Implement software. Amtex’s paperless effort didn’t come entirely without software investment. For instance, the shop added seats of JobBOSS’ Workstation Driver, which allowed shop floor employees to enter notes tied to a job for anything that might be needed the next time the job is run. No longer were notes hidden within operators’ personal notebooks or, even worse, locked inside their heads. “This effectively helped us share tribal knowledge,” Wagner said.

Regarding inspection records, Amtex’s quality assurance department uses Unipoint, an add-on for JobBOSS. “We can import the PDF drawing, and Unipoint will bubble it,” Wagner said, explaining that “bubbles” point to specific inspection points on the drawing and the acceptable tolerance.

At Amtex, every operator is responsible for quality, and the digital documentation describes who needs to inspect what and how often (such as first article or after so many pieces). The laser operator needs to inspect the material type, grade, and thickness, as well as the length and width of the flat. The press brake operators inspect to ensure proper orientation, especially for nonsymmetrical parts, and they measure every flange. Whatever additional inspection requirements remain are handled by QA.

Moving to paperless here added more error-proofing. When workers simply wrote their measurements on paper (the shop rolled out Unipoint before moving to completely paperless), mistakes could slip through—either an error in measurement, the recording of that measurement, or in the part. In the worst case, an out-of-tolerance part slipped through to the next operation, which led to more wasted effort, since QA would end up rejecting the work in the end.

Accessing the inspection records digitally, operators who type in a measurement that’s out of tolerance see an immediate red highlight on the screen. That makes it difficult for quality problems to slip through, since it forces employees to deal with the issue then and there.

Amtex also invested in SAP Crystal Reports, which the shop uses to generate automatic reports for scheduling. “We make reports for specific work centers and define what their tasks are, all color coded and organized by date,” Wagner explained. “If the job is hot, anyone on the front end can change the priority to a ‘1,’ and it will change the color to a purple job. So with a quick glance on the computer screen, everyone on the floor knows that those purple jobs take priority over everything else.

“Moreover, every five minutes we have an update. So an operator completes one job, looks at his list, and can tell by color which ones are first.”

On the back end, the company now uses KnowledgeSync. “That’s the background software that’s actually pushing things out to the shop floor, to folders on the server for each workstation. It also sends automatic emails to certain managers to show, ‘These are the jobs entered today and this is the material received today.’ This means all the managers can see what happened during a shift.”

Finally, the shop added SAP Concur, which helps automate the accounts payable process. “They now send all their invoices digitally,” Wagner said.

6. Go live and stop printing. After everyone received training on how to get and enter data, the shop continued to use paper and enter everything digitally at the same time. Again, the transition helped fix any issues before “pulling the plug” and going entirely paperless.

After three months, the shop stopped printing. A job on the floor now had only a small move ticket with the job number. Workers used terminals to access complete, up-to-date information for that order. “After three months, everyone was comfortable with the digital workflow, going to the job folder, finding all the information they needed, reading the job notes, even zooming in on drawings,” Wagner said, adding that managers now give employees refresher training on how and what to log into the system. “It’s about making sure everyone knows how to find the information they need to do their job.”

Making Work Life Easier

Amtex isn’t finished tackling information waste. To eliminate keystroking errors, it plans to implement bar coding. It also hopes to automate certain inspection tasks and develop a system for remnant management.

Today you won’t find a paper traveler anywhere in the shop, only move tickets attached directly to carts and pallets carrying the work. Going fully paperless took about a year and a half. The shop didn’t want to rush. After all, a faulty rollout would have created bad data, more headaches on the floor, and, even worse, resistance to change.

When Amtex finally did go paperless, longtime employees didn’t complain or stage a revolt. In fact, they welcomed the change. As Wagner put it, “No one said, ‘I just can’t do it.’ Going paperless really did make everyone’s life easier.”

When change makes life easier, change itself becomes easier—emotionally and logistically—fueling that virtuous cycle of continuous improvement.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI