The last time a journalist won a Nobel prize was 1935. The journalist who won it – Carl von Ossietzky – had revealed how Hitler was secretly rearming Germany. “And he couldn’t pick it up because he was languishing in a Nazi concentration camp,” says Maria Ressa over a video call from Manila.

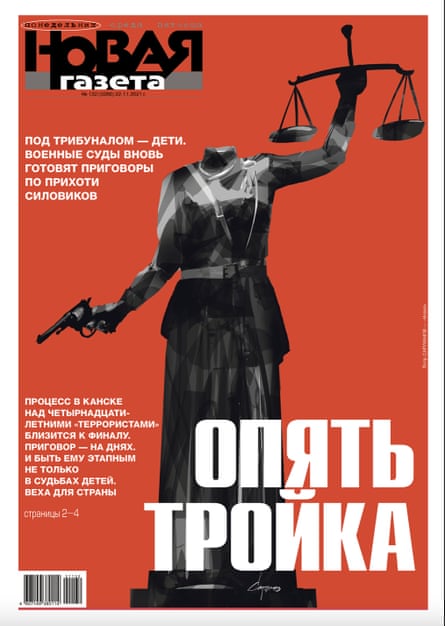

Nearly a century on, Ressa is one of two journalists who will step onto the Nobel stage in Oslo next Friday. She is currently facing jail for “cyberlibel” in the Philippines while the other recipient Dmitry Muratov, the editor-in-chief of Novaya Gazeta, is standing guard over one of the last independent newspapers in an increasingly dictatorial Russia.

For Ressa, whose news site, Rappler, has had its licence suspended and who wasn’t even sure she would be able to go and pick up the award until Friday when the government granted her permission, the parallels between the modern moment and the 1930s are all too terrifyingly obvious.

“It’s a huge signal that we are in that same kind of moment. We are on the verge of fascism. It’s different this time because it’s being enabled by technology but it’s also happening faster. There is this insidious manipulation happening at scale and humanity is wrapping its head around that.”

It is, she says, “a sliding doors moment”.

For Muratov, too – speaking in a rare interview over Zoom on a flying visit to New York last month – there is no doubt that the award is symbolic not just of an existential threat to press freedom but of a world on the brink. “I think our world has stopped loving democracy and has started reaching for dictatorships. Journalists are like independent media. They’re the defence line between dictatorship and war.”

The question is whether the world will notice what Christophe Deloire, the president of Reporters Sans Frontières, calls “a moment of truth”. He believes that the awarding of the Nobel to Muratov and Ressa is a clear danger signal to the world. “The systems that have been established for democracy and human rights are clearly in danger. Everyone can see it. We can feel this sense of emergency. And this moment represents a crystallisation of multiple different crises.”

If it is “a sliding doors moment”, for Muratov and colleagues in Russia, there seems to be no doubt about which way the doors are sliding. During his tenure at Novaya Gazeta, six journalists have been murdered including Anna Politkovskaya, who was shot dead in the elevator of her apartment building in 2006. But the present moment is chilling in a new and different way.

And there are other parallels between 1935 and now. Von Ossietzky won the prize for a series of exposés about how Germany was deliberately breaking the Treaty of Versailles and secretly rearming. He tried to warn the world of the dangers of a newly militarised Germany and he didn’t live to see the consequences of his reporting borne out. He died in 1938.

When I ask Muratov if we in western Europe should be afraid of Russia and its intentions, he doesn’t hesitate: “Yes, of course. There’s nothing to hide about that. Any dictatorship has very easy access to violence. Our country, my country, to my dismay, supports the [Belarus] dictator Lukashenko who’s essentially trying to start a war in the very centre of Europe.”

Muratov has been a less public figure than Ressa. He’s been at the helm of Novaya Gazeta for decades and has found ways to keep operating even as other independent news outlets in Russia have been driven into the ground. It’s for this reason that he’s been a more controversial figure too. In Russia, the news of his Nobel received a mixed reaction. The most high-profile journalist in Russia, Alexei Navalny, who’s also the leader of the opposition, is currently in a Russian prison.

It had been widely rumoured that he was in the running for the prize but that the Norwegian Nobel committee lost its bottle and caved in to pressure from the Kremlin. And, in Russia, Navalny supporters in particular were outraged and upset though Navalny himself sent his congratulations from prison, noting “what a high price those who refuse to serve the authorities have to pay”.

Muratov isn’t put out by the question. “The majority of those people have in fact changed their opinion,” he says. “And I’m very grateful to Alexei Navalny for the congratulations.” When he was asked a day before the award was announced who he thought should get it, Muratov said Alexei Navalny.

In Russia, there are increasing signs of darkness: that Russia is shifting, as an Economist headline put it last week, “from autocracy to dictatorship”.

“The situation, unfortunately, is very dark. There is a Stalinisation of the country that is currently occurring. Once again secret services and the secret police are playing a huge role. Secret services always make the decision but never bear the responsibility for the consequences of said decision.”

And Muratov is frank about the challenges – and accommodations – he’s had to make to keep operating. “I try to conduct dialogue with everyone but the cannibals,” he says from a cafe in New York on his first trip outside Russia since the prize had been announced. He’d travelled to attend the screening of a documentary, Fuck This Job, by another Russian journalist and filmmaker, Vera Krichevskaya, about the last independent TV station in Russia, Dozhd (Rain), and its battle-scarred owner, Natalya Sindeyeva. (The film will be shown on the BBC in January.)

If Novaya Gazeta has managed to negotiate a line between maintaining its independent reporting and not being crushed by the Kremlin, Dozhd has fallen on the other side of that line. Both Dozhd and Sindeyeva have been labelled “foreign agents” by the government as has the oldest human rights organisation in Russia, Memorial.

It’s the plight of Memorial – and hence the most fundamental human rights in Russia – that is currently terrifying them. The organisation is currently fighting for its survival in court after being accused of “justifying extremism”. For Muratov, Sindeyeva and Krichevskaya, together in New York, it’s another sickening irony: the organisation was founded by a Nobel peace prize winner, Andrei Sakharov, and set up as a deliberate effort to prevent the country falling again to totalitarianism.

Sindeyeva calls it “a catastrophe. We believe it’s the symbol at the bottom, when you can no longer go further down.” In Russia, she says, Stalin is being rehabilitated and Memorial was set up to remember “the victims of Stalinist repressions”.

Photograph: Mikhail Metzel/Sputnik/AP

For Deloire, the recognition of Ressa, Muratov and the importance of journalism brings a glimmer of hope. It’s a profound moment, he says, because it “crystallises the problems but also it crystallises the need to focus on solutions”. He points to President Biden’s summit for democracy, also taking place this week, as another faint ray of hope.

But it’s a precarious line.

Observers say the threat against Ressa is a taste of worse to come in the Philippines, where the son of the former dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, has joined forces with the daughter of the current authoritarian president, Rodrigo Duterte.

Ressa has spent much of the last four years trying to point out that none of this is happening in isolation and that the “assault on truth” is doing the same to western democracies as it has done to her country.

Muratov is even more gloomy. “It’s terrifying that countries that have been living in a democracy for so many years are rolling towards a dictatorship. That’s just a terrifying thought.”

Meanwhile, he says he’ll do what newspaper editors do: edit his newspaper for as long as he’s able. Or, as long as Vladimir Putin lets him.