Australia could be next to mandate a choice screen in a bid to break Google’s dominance of the search market.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is recommending it is given the power to “mandate, develop and implement a mandatory choice screen to improve competition and consumer choice in the supply of search engine services in Australia”.

A new report by the country’s competition watchdog concludes that interventions are needed to boost competition in the local search engine market and address harms flowing from Google’s circa 94% marketshare of search in Australia, such as barriers to entry for other competitors and the risk of lower quality services with what it dubs “undesirable features” — like more sponsored content vs organic search results…

Google’s grip on the local search market is also hampering new business models emerging — such as subscription options that don’t rely on ads (and data-mining users) to monetize Internet search.

The report gives the example of Neeva, a new, subscription-based search engine — which advertises itself as “the only ad-free private search engine” — and (unlike Google most other search engines) has no ads or affiliate links in search results — thereby offering “a different value proposition that consumers may desire”, in the regulator’s assessment.

“Google’s foreclosure of key search access points through the arrangements discussed in this Report limits the ability of these businesses to grow, and consumers’ exposure to new and potentially attractive business models,” the ACCC concludes.

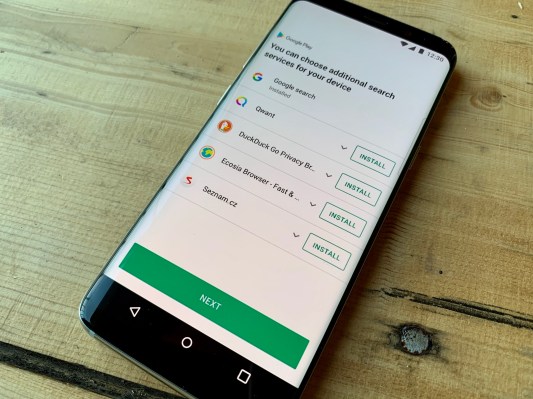

To tackle such problems, the regulator wants to be able to implement a search choice screen on Android devices which will provide users with a selection of options vs Google’s “predetermined default” — with the regulator saying that such a mechanism “can improve the ability of rival search engines to reach consumers”.

However the ACCC also wants to be responsible for developing the criteria around the application of a choice screen to specified service providers — which its report notes should be “linked to the provider’s market power and/or strategic position”.

That looks like a key qualification given Google has been offering a search choice screen in the European Union to users of Android smartphones for around three years — and there has been no notable shift in its regional dominance of search.

That can be blamed on the EU leaving it up to Google to determine how to ‘remedy’ the $5BN ‘cease & desist’ antitrust enforcement it issued against Google over Android back in 2018.

Google responded by adding a ‘choice’ screen of its own devising in the EU — which search rivals quickly decried.

They were especially incensed about a sealed bid auction model Google opted for — selling slots on the choice screen to rivals, without needing to pay to continue displaying its own search engine on the very same screen of course.

This resulted in Android choice screens that were filled with an uninspiring parade of Google-style ad-targeting wannabies or else Google itself as the offered ‘choice’ — almost entirely excluding pro-privacy or not-for-profit alternatives who were unable to outbid data-mining rivals.

The entirely predictable result was that Google has maintained its iron grip on Europe’s search market. And laughed all the way to the bank.

Eventually the European Commission did step in — and, this summer year, Google announced it would drop the auction model and instead let search rivals appear for free.

However alternative search engines, such as the non-tracking DuckDuckGo, remain highly critical of remedy, arguing that for a choice screen to truly work regulators must tackle the whole suite of damaging defaults Google applies to lock users to its products.

The EU implementation, for example, only applies to new Android devices (and not also to Chrome), and only on set-up or factory reboot of a device. DuckDuckGo’s counter suggestion is that regulators must make search competition a single click away at all times.

Australia’s watchdog appears aware of such pitfalls — writing: “The development of a choice screen and its implementation should be subject to detailed consultation with industry participants and user testing, and there should be careful consideration of its interaction with other measures proposed in this Report.”

Notably, it’s leaning towards the choice screen applying to both new and existing Android mobile devices — which is immediately a considerably broader application than Google chose to apply in the EU (giving itself a free pass to keep applying its damaging defaults on the hundreds of millions of already in-play Androids).

The ACCC also stipulates that an Australian Android choice screen should be free for search engines to participate in. So the lesson of Google’s self-serving EU auction model has clearly trickled down under.

Australia’s watchdog also wants wider powers to be able to effectively tackle the lack of competition in search — suggesting it will need measures to restrict a provider (“which meets pre-defined criteria”) from tying or bundling search services with other goods or services; and perhaps also limit the ability of a provider to pay for certain default positions.

The report also floats the idea of “potentially mandating access to specified datasets for rival non-dominant search engines”.

The regulator suggests rivals may need access to Google’s click-and-query data — “and potentially other datasets” — though it adds that this would need to be subject to “extensive consideration of privacy impacts, and careful design and ongoing monitoring to ensure there are no adverse impacts on consumers”.

“While there are a number of factors that contribute to the quality of a search engine, click-and-query data is a critical input,” the report goes on. “In limiting rivals’ ability to reach consumers at scale, Google has ensured it maintains access to an unrivalled dataset, allowing it to continuously improve the quality of its search results in a way that its competitors cannot, and reducing the extent to which rivals are able to scale and compete against Google.

“This has flow on effects for the ability of rival search engines to monetise their services, effectively self-reinforcing Google’s dominance in search. Google’s position means it can offer greater sums to suppliers of browsers and OEMs to be the default search engine. Rivals are thereby foreclosed from accessing users and the necessary click-and-query data to improve their search engine service, further raising barriers to entry and expansion, and extending and entrenching Google’s dominance in search.”

While the ACCC is considering some meaty interventions against Google’s dominance of search, actual action appears some way off — with a fifth interim report, that’s not due until September 2022, set to consider a framework for the proposed rules and powers, along with a broader assessment of the need for ex-ante regulation for digital platforms — “to address common competition and consumer concerns we have identified across digital platform markets”.

The reports are part of work ordered by the Australian government last year — when it instructed the regulator to conduct an inquiry into digital markets and report back every six months. However the final report is not due until March 2025.

The EU of course has already proposed ex ante rules to tackle platform giants, under the Digital Markets Act, which was presented at the end of last year. Though is likely years off being adopted.

The UK is also working on a competition reform that will give regulators pre-emptive powers over tech giants who are deemed to have strategic market power. But, again, a dedicated Digital Markets Unit is pending a suite of legislative powers.

While Germany — which is ahead of the pack — updated its digital regulations at the start of this year, bringing in ex ante powers to tackle platforms. Its competition watchdog, the FCO, is in the process of assessing the market power of a number of tech giants to determine how it might intervene to support competition.

Germany suite of probes includes a close look at Google’s News Showcase product, through which the tech giant licensed news publishers’ content by inking closed door commercial deals which risk playing large publishers off against smaller ones, among other competition concerns.

Australia has already passed legislation in this area — putting a news bargaining code into legislation back in February that applies to both Google and Facebook.

Reached for comment on the ACCC report, Google sent us this statement attributed to a spokesperson:

“People use Google Search because it’s helpful, not because they have to and its popularity is based on quality that’s built on two decades of innovation. Android gives people choice by allowing them to customise their device — from the apps they download, to the default services for those apps. Preinstallation benefits users by making it easier for them to use services quickly and easily. We are continuing to review the report and look forward to discussing it with the ACCC and Government.”