- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Alternative hydroforming tech dispenses with bladder, achieves 60,000 PSI

Unconventional metal forming technology called fluidforming forms harder materials, makes finer features

- By Eric Lundin

- August 30, 2021

- Article

- Hydroforming

It’s rare that two technologies compete against each other directly for long. Usually one offers a better value and the other becomes obsolete. A more frequent occurrence is that two similar technologies compete indirectly, each occupying a portion of a market. So it is with stamping and hydroforming.

The former is the grandaddy of metal forming, a process with origins that go back thousands of years and industrialized in the 1890s. Performed on mechanical, hydraulic, and servo-driven presses, the process is augmented by innovations and expertise that provide nearly endless combinations of capability, capacity, versatility, and speed. The essence of the process, pressing a sheet of metal between two matched dies to form it, doesn’t do justice to the vast industry the process spawned, the countless books and trade journal articles written about it, and the endless amounts of accumulated expertise in the field.

Closely related is hydroforming. It had some traction in the automotive industry in the early part of the 20th century, and tubular hydroforming found lucrative niches in making some intricate plumbing components and musical instruments many decades ago. When used for forming sheet, hydroforming uses one die and a bladder. As the bladder fills with fluid, it expands and forces the sheet to conform to the die. A similar method uses a diaphragm; as the cavity behind the diaphragm fills with fluid, the same process takes place. Forming a tube is a matter of using fluid to expand the tube from the inside. Hydroforming tube relies on hard tooling and doesn’t make use of a bladder or a diaphragm.

Hydroforming can form more intricate shapes than two stamping die halves can form, so often a single hydroformed component can replace a conventional assembly of several stampings welded together. In cases like this, a hydroformed component often is lighter in weight, more structurally sound, and faster to manufacture. The tubular mode of hydroforming does much the same for tubular components.

However, hydroforming isn’t solely in the domain of conventional hydroforming presses. Another technology that uses a forming fluid delivers substantially more force and therefore can form stronger materials, more complex shapes, and finer features than conventional hydroforming. It’s carried out on a machine known as a FormBalancer, a product of FF Fluid Forming GmbH (Lastrup-Nieholte, Germany) and available in the U.S. from a separate company, FluidForming Americas LLC (Hartsville, Tenn.).

Sealing and Forming

The extent of a process’s forming capability is a function of the machine’s pressure-building capability, which hinges on sealing capability, which in turn is an outcome of the machine’s design.

While nobody doubts the viability of conventional sheet hydroforming, one of the design elements—the diaphragm or the bladder—does set a limit for the pressure.

"Conventional hydroforming presses are limited to 10,000 to 15,000 pounds per square inch,” said FluidForming Americas’ Chief Technology Officer Jurgen Pannock, Ph.D. “A FormBalancer can achieve up to four times that amount of pressure.

“On a conventional hydroforming press, any slight misalignment of the die or any gap anywhere in the system is a leak path,” continued Pannock. “The potential for a leak limits the forming pressure. Diaphragms and bladders also impose limitations. They can only withstand so much pressure before a hernia forms or it bursts altogether. That’s not an issue with the FormBalancer.”

A FormBalancer isn’t a large or heavy unit. A common industrial floor usually is sufficient to support the machine; it doesn’t require a special foundation.

Fluidforming can handle nearly any material in any thickness up to about 18 ga. and the machines’ forming capability runs from 30 by 30 in. to 50 by 50 in. FormBalancers also can be set up to run tubular products. Feeding the tube into the machine can be augmented with an assist force, providing more forming capability than would be possible without it.

The three controlled parameters—clamping pressure, forming pressure, and fluid velocity—can be used to manipulate how the material flows into the forming cavity during the forming process. These parameters can be varied throughout the process.

“Because material flow is a part of the forming process, it doesn’t generate the forming marks that are often associated with hydroforming or stamping,” said Pannock.

“While the quality of the die matters, the bigger factor is that the forming process doesn’t sandwich the material between two mated dies and doesn’t have a bladder that interferes with the metal deformation,” he said. “This makes it possible to make undercuts, organic forms, deep-drawn parts, and other challenging parts that would either be impossible to form or prone to wrinkling when made with other processes or traditional hydroforming.”

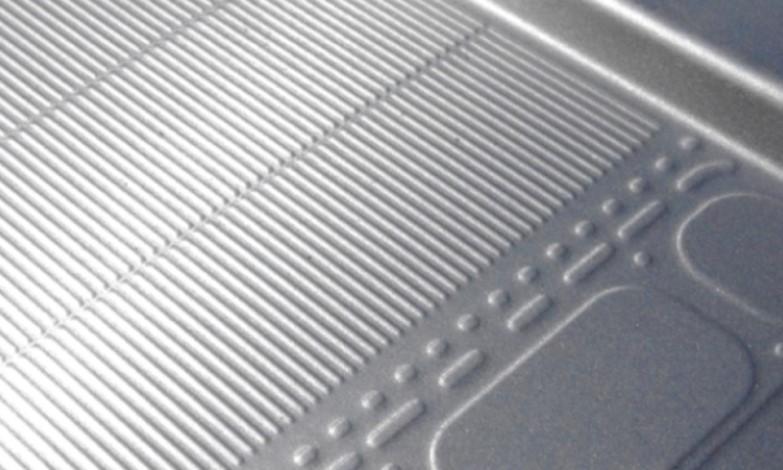

Beyond forming difficult and intricate shapes, the process produces parts with very good surface characteristics.

“For kitchen applications like mixing bowls and baking pans, parts come out nearly ready to ship,” said Paul Benny, the company’s CEO. “Often the parts need a quick polish and that’s it.” As such, it’s compatible with prepared surfaces that often are damaged by forming processes, such as polished, patterned, and etched materials.

The same surface characteristics also play out well in forming a valve body.

“Traditionally, valve bodies are cast, and castings are porous,” Benny said. “Fluidforming enables the substitution of one-piece porous casting with a valve body made from two formed hemispheres. It has the same function, but it’s much easier to clean and keep sanitized. It’s a good solution for the food and beverage industry, as well as the medical and pharmaceutical industries.”

Tooling Considerations

Some parts that are challenging to form by stamping are easier to form by this process, according to Pannock.

The fluidforming process can make features so fine that they appear to have been stamped. Unlike conventional hydroforming, which uses a bladder or a diaphragm as a universal die, fluidforming uses only water as the forming media, facilitating intricate features.

“If a part needs a lot of forming and a process that typically would need a set of progressive dies, a FormBalancer often can make the part in one hit with one die,” Pannock said. “The cost of a single die can be less than 10% of the cost of a set of progressive dies.” The process also helps to improve part accuracy and repeatability. According to Pannock, dimensional variations often are less than 0.005%.

And while the potential of a die crash is an expensive risk when using other pressing methods, the doesn’t exist when using a FormBalancer, Benny said.

“When you’re hydroforming, a valve failure can cause a die crash,” he said. “When stamping, if the loading system loads two sheets of material, the dies can crash. When the process uses just one die and a bladder, or one die and water, it eliminates the risk of a die crash.” This gets around an expensive problem and a time-consuming remedy.

Benny noted that the FormBalancer can be used with a variety of die materials. Of course, tool steels are options, but this process works well with tooling made from plastics and composites, as well as additively manufactured tooling.

“Often a tool can be made in a day or two,” Pannock said. “In nearly every case, it takes less than a week.” The tooling lends itself well to options and modifications.

“It’s east to modify a die to change a part’s characteristics,” Benny said. “We can add a rib feature to the die to impart a rib to reinforce the part, and we can use inserts also.” For example, it’s easy to make custom-branded items for a variety of customers by using interchangeable inserts that bear each customer’s company name or logo.

Process Development

As is the case for nearly every equipment vendor in the metal fabrication industry, FluidForming Americas is both an engineering consultant and an equipment retailer.

Pannock and Benny are long on experience in developing dies; determining the best combination of clamping forces, forming force, and fluid velocity; doing some trial-and-error work in blank development; making adjustments to how blanks are held or fed throughout the forming process; and all of the other work that goes into process development.

“Finite element analysis (FEA) does an excellent job in predicting outcomes,” Pannock said. “It’s accurate in calculating hardening stresses, the amount of stretching, and the material’s final thicknesses. In cases where FEA reveals a potential problem, we rely on years of forming experience to modify the process and run a new simulation.”

Their expertise—and access to FEA—aren’t just available to potential clients interested in buying a FormBalancer. The company is well aware that many of its clients don’t have the volume to justify such an investment. Many who are interested in the process, and the products it makes, need occasional orders of just a few dozen items. To that end, the company takes on the role of a component manufacturer, using its in-house expertise and equipment to make short production runs.

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI