In the 1960s Chuck Close, fresh from art school, was sitting in a New York restaurant when Jasper Johns walked in, passing by his fellow diners in total anonymity despite the older painter’s great fame. After seven decades of self-portraits, Close, who has died aged 81, never suffered the same fate, his face recognisable to generations of museum-goers. In 2017 this storied career abruptly ended following sexual misconduct allegations.

Close painted on a huge scale, the acrylics or oils flatly applied with little discernible brushstrokes. He always started with a photograph as source material, rigidly divided by an overlaid grid, which he would replicate, colours and forms, square by square, on to canvas using a variety of tools including razorblades, electric drills and airbrushes. The artist also brought the faces of his peers from obscurity, completing portraits of Kiki Smith, Alex Katz, Cindy Sherman, Roy Lichtenstein and other artists, as well as the more readily recognisable Barack Obama, Al Gore, Brad Pitt and Kate Moss.

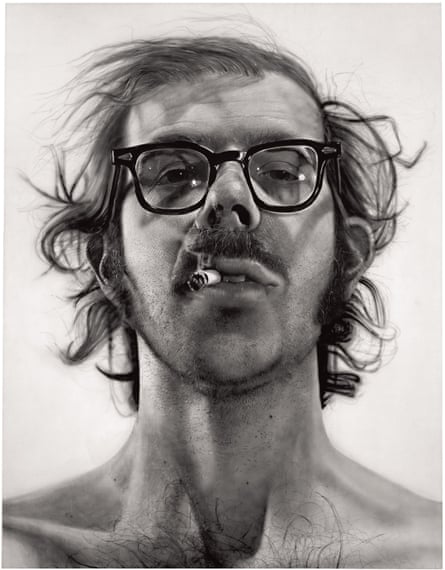

Close hated the term “photorealist”, but for much of his early work, made in an abrupt break from the abstract expressionist paintings he produced as a student, it was apt. The 1967-68 Big Self-Portrait, across a 2.7-metre-high canvas, shows the artist, painted using black and white acrylic paint, with his head tilted so we peer up his nostrils. A cigarette hangs loosely from his lips and hair creeps up the top of his bare chest. Working on such a scale, Close likened himself – and the viewer of the work – to the diminutive characters of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. “Lilliputians crawl over the body of this giant, maybe not even knowing that they’re on a giant until they fall into a nostril or trip over beard stubble,” he said in 1995. In 1969 he painted Philip Glass in the same fashion, the composer’s nose likewise tilted up and his mess of boyish curls casting a shadow across the forehead. “I’m very interested in a nose as a shape,” Close said. “I’m also interested in its edges and the surface information scattered across it.”

The 70s saw the artist embrace colour, alongside an enlargement of the individual squares of the guiding grid he used in the process of a work. This gave his paintings a more abstracted, pointillist style. “I am not trying to make facsimiles of photographs,” Close said. “Neither am I interested in the icon of the head as a total image. I don’t want the viewer to see the whole head at once and assume that that’s the most important aspect of my painting … My main objective is to translate photographic information into paint information.”

In 1988 Close collapsed at an awards ceremony in New York, owing to an occlusion of the anterior spinal artery. Lying in the hospital, initially paralysed from the neck down, Close assumed he was going to have to give up painting and take to conceptual art. “But I was going to miss the activity of pushing paint around. So pretty soon, I thought: I’m going to get the paint on the canvas if I have to spit the paint on the canvas. They found me a room in the basement, an art therapy room.”

He strapped a paintbrush to his wrist with bandages and, regaining movement in his arms, slowly got back to work, his disability having little bearing on his subject interests or painting style.

Janet (1989), shows the artist Janet Fish grimacing through a rigid series of oil paint markings, an aesthetic that continued that of the last portrait completed before the artist’s hospitalisation, a 1987 portrait of a glum-looking Katz. A 1993 portrait of Smith is made up of thousands of individually painted abstract blobs contained with a square grid.

Born in Monroe, Washington, Chuck was the son of Mildred (nee Wagner), a piano teacher, and Leslie Close, a plumber and sheet metal worker who died when his son was 11. Chuck himself was bedbound that year with kidney disease. Mildred, left to raise the boy alone, supported his artistic interests against the background of her own breast cancer diagnosis. Chuck had severe dyslexia, which led him to struggle at high school, but he blossomed during evening art classes at Everett Junior College.

In 1960 he went on to the University of Washington to study art, where he saw himself as a “third-wave abstract expressionist”, inspired by the likes of Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning, and completed a master’s at Yale alongside Richard Serra and Nancy Graves.

After studying at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Vienna in 1964 on a Fulbright grant, Close returned to the US the next year, teaching at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where he had his first solo exhibition, before moving to New York in 1967. There he taught at the School of Visual Arts, where he met his first wife, Leslie (nee Rose), one of his students, while spending his nights at performances and parties in artists’ studios or at Max’s Kansas City, a bohemian nightspot on Park Avenue.

Immersed in the New York scene, Close found ready models in his artistic peers. “It’s hard to make art when nobody gives a shit. In an art ghetto we can convince ourselves that what we’re doing is a very important activity because we’re surrounded by other people who agree that it is.”

In 1971 he had his first major museum exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, introducing colour for the first time with Kent (1971), in which a freckled friend with a crooked nose is shown of dour demeanour across a 2.5-metre-high canvas. In 1980 the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis staged the artist’s first retrospective, Close Portraits, which travelled to the St Louis Art Museum, Missouri, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, before closing at the Whitney Museum in New York. During this period he experimented with painting with his fingertips, pressing them into an inkpad to make works such as Keith/Square Fingerprint Version (1979), and also with photographic collage, including Self-Portrait/Composite/Six Parts (1980), a 4.3-metre-high work made up of Polaroids.

Another touring retrospective opened at MoMA, New York, in 1998, travelling across the US and ending at the Hayward Gallery, London, the following year.

Close and Leslie divorced in 2011, and he married the artist Sienna Shields in 2013; they separated two years later. “It turns out that a wheelchair is some sort of funny babe magnet,” he said that year. “When I’m going through the Miami Art Fair, thousands of beautiful women are hanging all over me.”

In 2017, Close was accused by several women of verbal sexual misconduct at various times between 2005 and 2013. They described how he invited them to his studio to pose, before asking them to undress for the portrait and making vulgar comments. Having first denied the allegations, Close went on to apologise. Nonetheless, the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC cancelled a planned exhibition of 30 works that year and, beside shows at the Hong Kong outposts of his commercial dealers, White Cube and Pace Gallery, the controversy brought his exhibiting career to an end.

Close was given a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in 2013, amended to frontotemporal dementia two years later.

He is survived by his daughters, Georgia and Maggie, from his first marriage, and four grandchildren.

Chuck (Charles Thomas) Close, artist, born 5 July 1940; died 19 August 2021