Capturing the Anthropocene: Changing Depictions of the Climate Crisis

Magnum photographers discuss alternative approaches to communicating climate change

Magnum Photographers

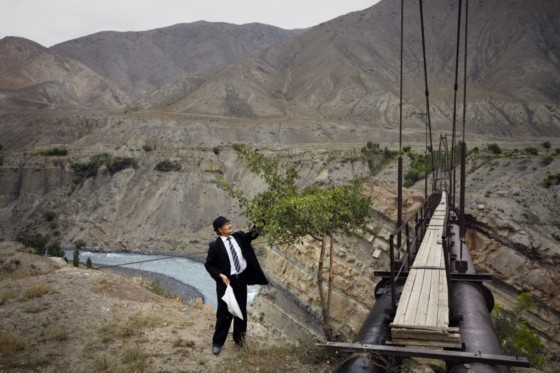

In this study of new photographic approaches to issues of climate change, Magnum photographers Sim Chi Yin, Cristina de Middel and Jonas Bendiksen speak to writer Georgina Collins about their practice. Alongside this, Toby Smith from the charity Climate Visuals shares strategies on revolutionizing how we communicate current environmental crises.

In the summer of 2019 unprecedented temperatures were experienced across Northern Europe, with at least 12 countries breaking national heat records. July 2019 was the hottest month on earth since temperature records began in 1880. This was, and is, indicative of the growing disaster the planet is facing in the form of climate change. World Weather Attribution found that there was an extremely low probability of these temperatures being reached (for instance in France less than about once every 1000 years) without climate change. Climate change made this extreme weather around 100 times more likely. Put in these terms, the summer of 2019 sounds apocalyptic- and in many ways it was. The European Forest Fire Information System found that in 2019 1,300 square miles of continental Europe were burned (15% more than the decades annual average), but the vast majority of the photography that we saw told a different story. Beach days, sunbathing and icecreams predominantly featured in photographs of the summer.

"It’s this cynicism that they hope photography can help overcome in order to build our collective investment in reducing environmental harm."

-

The role and responsibility that photographers themselves have when photographing events related to the climate crisis has been subject to increased attention in recent years. Photography is a powerful visual medium that can be used to educate, raise awareness and inspire action, and as such there is a strong argument that this comes with an implicit responsibility about the representations of an issue being made to the public. Visual storytelling can shift public perception and behaviours, which in turn influences national and international responses to the crisis. Climate Visuals is a non-profit built around this relationship between photography and social action; focused on changing the type of imagery used in relation to the climate crisis, so that it is not just “illustrative but truly impactful and inspires change,” as project lead Toby Smith states. The group is founded in research in social science; they use evidence gathered from focus groups in Europe and the USA to examine the emotional responses to different photographic depictions of the climate crisis. Smith says they want to see a more compelling and diverse visual language around climate change: less “polar bears, factories and glaciers… all of which have the really neat trick of signifying climate change, but still producing a large amount of cynicism and inactivity”. It’s this cynicism that they hope photography can help overcome in order to build our collective investment in reducing environmental harm.

It is perhaps because the climate crisis has presented a new challenge to practitioners (how do you go about capturing an existential threat, moving at literally glacial speed, in a single frame?) that imagery has often felt reductive in the face of a challenge on the scale of the climate crisis. Magnum photographer Cristina de Middel, who covered the 2019 wildfires in Brazil, describes exactly this: “The drama and the destruction that was happening was hard to capture and express with just images of flames and burnt pieces of the jungle. The scale of everything was overwhelming and by framing that reality, and deciding which piece of it would become a picture, I was actually losing the magnitude of it”.

“I think it depends on what you expect photography to do or what you expect of the photographer,” says Sim Chi Yin in reference to the challenges posed by photographing the climate crisis. “I think this is a deeper question about whether photography and photographers are expected to be advocates and activists as well,” she continues. “There are things that may translate photographically into climate change and some things that don’t”. Sim has been working on her project Shifting Sands, documenting the social and environmental cost of the land reclamation industry in East and Southeast Asia. Previously taking an ‘infrastructural gaze’, shot at ground level, capturing the people and places affected, she has since adopted a birds-eye view, producing strikingly beautiful other-wordly landscape photography. It’s not uncommon to hear criticism of photography, particularly in the realm of editorial, for making terrible things look too beautiful. This is an all too familiar conundrum for Smith in his work at Climate Visuals: “I spend a lot of my time arguing with the media about social science but the other side is that I spend a lot of time arguing with social scientists about the subjective qualities of photography,” he says.

In essence, though accurate and impactful depictions of the climate crisis are the goal, the photos need to be published if you’re going to achieve that, and the pictures have to be good or that’s not going to happen. For Sim Chi Yin, the beauty of her Shifting Sands images were an entirely deliberate move away from the more ‘ditactic heavy-handed approach’ she once took; here, the aestheticization of a challenging topic is a strategy to encourage on-going engagement in a difficult conversation.

There is, for obvious reasons, an excess of what might be referred to as ‘disaster photography’ in coverage of the climate crisis. The aesthetic properties of these images ‘sell’ but, according to Climate Visuals research, don’t create a meaningful, or – perhaps more accurately – an actionable, response in the viewer. The Global South has already suffered a disproportionate number of climate disasters, simply because populations and ecosystems in tropical, higher-latitude regions experience the worst effects of rising global temperatures. As a result, you’d be forgiven as a consumer of photography for thinking that climate change wasn’t affecting Western Europe. This echoes the experience of de Middel: “I think we are still in a stage where environmental issues are perceived as something exotic and distant, even if they are not. Despite the frequent vivid reminders of the seriousness of the situation, the threat sounds distant and that makes the sense of urgency very difficult to convey”. Many people don’t relate to these images beyond the shock and awe of the moment, because it doesn’t resonate with their own demographic construct. This in turn, has resulted in the othering of communities in the Global South as they are continually represented as victims, often by foreign Western photographers, as a way to capture the climate crisis in a way that’s seen as visually appealing. Rarely do we see the photography of practitioners with lived experience of climate disasters in the Global South, and rarely do Western photographers’ cameras turn to document the effect of climate change closer to home.

This, at least in part, can be attributed to a general desire for simple narratives when taking on an issue as huge and amorphous as the climate crisis. And, in a parallel and more practical sense, the causes and impacts of climate change are more compelling and cinematic than, say, the solutions to the climate crisis. So, reaching Net Zero – achieving an overall balance between emissions produced and emissions taken out of the atmosphere – has the potential, in Smith’s own words, “to be a really boring photographic essay”. There is however, an “extremely powerful” way to communicate the issue, by combining images of disaster with images of solutions and action.

But this in itself presents a challenge, and gets to the heart of the problem of documenting the climate crisis in photography; how can photographers tell more nuanced and innovative stories within their relatively narrow medium? Jonas Bendiksen, who documented Bangladeshi communities experiencing chronic flooding, says that “photography has a tendency to oversimplify; it’s not the easiest medium to formulate a complex thought process; it tends to rely on ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ and be less focused on the complexities of things”. He’s increasingly interested in the ‘grey zones’, for instance how photography of Western consumerism also provides an important perspective on the climate crisis, but is frustrated by limitations of the platforms that are available. There’s an increasing pressure, driven by social media, for single images or a couple of slides to have an impact, to be easily-digestible. Climate change, particularly its effect on the Global North, will not reveal itself so it can be fitted neatly onto social media feeds. The commodification of environmental images, which we could describe as the photograph-social media industrial complex, also leads to an oversaturation of images, resulting in just the apathy that the Climate Visuals is endeavouring to avoid.

Some are already looking to overcome these limiting factors, like de Middel. “As a communicator, I find it interesting to explore new ways of presenting issues whose narratives are already exhausted and who suffer from over-reporting,” she says, “I believe it is part of the job to keep the audience interested and curious to know more”. Sim Chi Yin says “I think it’s no longer enough just to make the pictures and put it through an editorial channel” — where it is consumed for a day, and then forgotten about. As Sim grew increasingly frustrated with the limits of single image photography, she experimented with exhibition installations, performance lectures, and for her Shifting Sands project, a VR installation that has yet to be completed due to lack of funding. She says, “I think we live in a different time, and this period of information and imagery-saturation needs different types of visual strategies for storytelling”.

Smith makes it clear that it’s not just the photographers and content generators, who sit at the wide bottom of the ‘pyramid’ of the photography industry, who can play a role in shifting public perceptions of the climate crisis. It’s also the agency, distribution, and media companies who occupy the top of the pyramid and choose what is and isn’t seen by a wider audience. There needs to be the funding and interest to commission work that can take on the long story-arc of the climate crisis in all its complexity.

Photography is an enormously powerful way of communicating the challenges posed by the climate crisis, inspiring outrage, anger and fear. But it also has greater potential to engage people beyond these fleeting emotions – giving form to the sometimes abstract nature of the challenges facing us – moving people to hope and action. Visual storytelling can and should be a crucial tool for building a social mandate around tackling climate change, but as many have been forced to take stock and adjust to the new reality of the climate crisis, so too will the world of photography.