When the Tokyo Olympics were postponed for a year, the widespread presumption in the corridors of International Olympic Committee power was that they would eventually go ahead at a time when the world was no longer in the grip of a global pandemic. Covid would be contained. Vaccine roll-outs would be complete. If not completely free of its latest viral scourge, the world would at least have a firm handle on it. The Games would mark a celebration of sorts; the first truly global jamboree to be staged in the post-pandemic era.

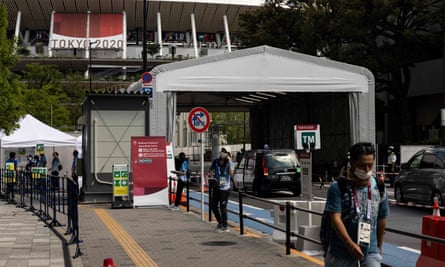

With less than a week to go until the opening ceremony it now seems more abundantly clear than ever the IOC optimism that originally seemed misplaced was ludicrously wide of the mark. With 11,000 athletes and another seven or eight times that number of coaches, support staff and media workers converging on Japan, it is increasingly obvious that staging this potential super-spreader event is a dreadful idea. Even before a flame has been lit, a starting gun fired or a medal presented, the first positive Covid-19 test has been recorded by a foreign visitor in the Olympic village.

The people of Japan do not want these Games. They are terrified of the horrors these Games may visit on their country. And yet they are being forced to host them against their will by an IOC to whom their leaders have been contractually beholden from a time long before the first case of virus was reported from Wuhan, China on 31 December 2019. The consequences of breaking that contract would be financially catastrophic so the Games will go ahead with other potentially devastating human costs on which no monetary price can be put.

In May, medical experts announced the daily infection rate in Tokyo would have to fall below 100 in order for the city to safely hold the Olympics. Last Thursday, 1,300 new cases were reported, the most since January. Among those to test positive were an unidentified athlete, five Olympic employees and eight members of staff at a hotel hosting members of the Brazilian team.

Confronted with these statistics, the IOC president, Thomas Bach, bullishly claimed “the risk for the other residents of the Olympic village and the risk for the Japanese people is zero”.

With the thick end of up to a million visitors, many of whom have received no inoculation against the virus, converging on Tokyo from all over the world, Bach’s confidence seems rather misguided and based on nothing more scientific than a wing and an Olympic prayer. In the shoes of an American high school principal, it is not difficult to imagine him insisting sports day go ahead despite the presence of teenage shooters roaming the campus.

Almost one-third of Japan’s 126.3 million population is 65 or over and not all of these have been vaccinated against the virus yet. A little under two months ago, four per cent of the population had received both their jabs, although the figure is now nearer 20%.

According to The Lancet, the slowness of Japan’s rollout is down to the strict regulatory approval of vaccines, delays in their importation and a paucity of qualified medical personnel to administer them in a country where only doctors and nurses are permitted to give the injections.

The upshot? Vast swathes of the Japanese population remain unvaccinated, many of whom will be tasked with providing hospitality for the deluge of foreign delegations who will need to be fed, watered and driven around in the coming weeks.

Even those who have been vaccinated may find themselves exposed to risk – since the night of England’s defeat by Italy in the Euro 2020 final, four of my friends have tested positive for Covid-19, with all but one among them having had both their vaccinations. While there is no guarantee the football was a factor in their infection, one attended the match at Wembley while the other three watched it together in the same busy pub.

With Tokyo in a state of emergency and local and foreign fans banned from attending almost all events, packed stadiums and crowded watering holes are unlikely to be a factor in these Games, which will be staged solely for the benefit of its organisers, the Japanese economy, the participating athletes and a TV audience unlikely to be particularly enthused by the sight of medals being contested to the spooky sound of no hands clapping. A penny for the thoughts of those long jumpers, pole vaulters and high jumpers in the habit of soliciting rhythmic assistance from those in the stands before particularly important leaps.

“To gain the understanding of our people, and also for the success of the Tokyo 2020 Games, it is absolutely necessary that all participants take appropriate actions and measures including countermeasures against the pandemic,” said the Japanese prime minister, Yoshihide Suga, during a meeting with Bach last week.

Awarded the Games in 2013 as a show of trust that they had recovered from the March 2011 triple-whammy of an earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster, Tokyo must wait and hope that the ceremonial lighting of the Olympic flame at Friday’s opening ceremony does not also ignite the touch paper for more tragedy and devastation.