- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Our Publications

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Experts share advice about bringing 3D printing in-house

How shops can get off to a good start when adopting 3D printing technology

- By William Leventon

- July 14, 2021

- Article

- Additive Manufacturing

Jabil’s manufacturing facility in Auburn Hills, Mich., cut 80% from the time needed to produce custom tools and fixtures by 3D-printing them in-house. Jabil

It’s probably safe to say that no manufacturer today with even a rudimentary connection to the outside world is unaware of 3D printing. And most have no doubt heard stories about the myriad capabilities of additive manufacturing.

But for shops new to the technology that are more interested in what AM can do for them than in gee-whiz tales about the technology, they need to know the best way to get started with 3D printing and successfully integrate it into their conventional manufacturing operations.

Print What’s Needed

A good way to begin is to identify potential applications for additive. A 3D printer can be a valuable addition to a machine shop by making the tooling and fixturing needed to produce end-use parts. In many cases, machinists might spend half their time on this task—time that is especially valuable these days, given the difficulty many shops have finding skilled operators, noted Tripp Burd, manager of strategic applications engineering at Markforged Inc., Watertown, Mass.

With a 3D printer assigned to the job, however, machinists simply upload a geometry into the software, hit the print button, “and go back to doing high-value-add stuff that requires their skill set,” Burd said.

In addition to tooling and fixturing, many shops are using 3D printers to build polymer nests, which hold parts being processed on automated machines. “We have seen a massive amount of interest in additive because it frees up [shops] to do some crazy [nesting] geometries that they couldn’t do with traditional machining,” said Paul DeWys, sales engineer at Forerunner 3D Printing, a Coopersville, Mich., parts-maker.

“It is also way faster in a lot of cases,” he added, slashing weeks off production time by eliminating the need for casting and moldmaking.

DeWys also said there’s strong interest in using AM to create components for collaborative robots. Companies are turning to cobots to supplement their human workforce. But these small robots are limited in load capacity, “so every ounce matters when designing end-of-arm gripping solutions for them,” he said.

For these applications, Forerunner can print a honeycomb structure made of nylon that is plenty strong and stiff but lighter than a solid gripper. DeWys said that nylon weighs roughly half as much as aluminum. “So we help these small robots gain load capacity, but they still have a high-performance end-of-arm tool.”Smoothest Possible Integration

Whatever the application, integrating 3D printing into a conventional manufacturing operation can present problems. But there are ways to make the process go more smoothly. One is to designate a “champion” for the technology, according to Burd.

“For a company just getting started [with AM], it is important to have somebody who is going to lobby for it internally and provide air cover as some experimentation and new applications are tried out,” he said. Ideally, the champion will be someone with the necessary CAD skills to create files for the printer.

Forerunner 3D Printing additively manufactured this vacuum nest, which was designed with a cold-air blow-off. Made of Nylon 12, it grabs plastic parts from an injection mold. Forerunner

In addition, DeWys stressed the importance of starting small and enabling staff people to learn on their own. “Instead of spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on a machine that just sits there because no one is sure what to do with it, start with a $10,000 investment in a desktop [filament-style] machine,” he advised.

The machine should be placed in an area where people will walk by it every day. “If you’ve got people who like to try new things, enable them to get on that machine and start printing stuff,” DeWys said. “In the early days, it will probably be simple things like a pencil organizer or a little replacement part for something in the office. But as they get more comfortable using the machine, all of a sudden you’ll see that they’re printing some nesting to go onto a machine or a custom hand tool to solve an ergonomics issue on the assembly line.”

As time passes, he added, shop personnel will start to push the printer’s boundaries. And eventually they’ll start to wonder what they could accomplish with a more expensive printer.

For those embarking on the 3D printing journey, it can pay to take advantage of outside help that’s available. For example, Markforged offers a training program through its Markforged University that can be accessed online and at the company’s headquarters. In addition, the company will hold classes at the facilities of larger customers.

Once shops have their new AM system up and running, Burd believes they should take it as seriously as their other manufacturing processes. “A lot of people say the 3D printer is a neat tool and adding value, but they don’t know how much,” he said. “Additive is not just a side-project toy. It should be treated like any other investment [in terms of] ROI and payback period.”

To that end, he recommends using key performance indicators or other measurement tools to objectively track the value AM is adding to an operation.

Success Story

An example of successful AM integration can be found at the Auburn Hills, Mich., manufacturing facility of Jabil Inc., St. Petersburg, Fla. Measuring roughly 250,000 sq. ft. and employing about 650 workers, Jabil Auburn Hills performs contract manufacturing work for industrial and health care customers.

In the past, Auburn Hills worked with outside shops to design and produce tooling for its manufacturing processes. It was an iterative process that required a good bit of time and communication. So a few years ago, management decided to take control of the process and started 3D-printing jigs, fixtures, tooling, and other shop devices.

The Auburn Hills team enlisted the assistance of Jabil Additive, an engineering group within Jabil that provides AM training and guidance to all of the company’s manufacturing facilities.

“We spend a lot of money on jigs, fixtures, and tooling,” noted Rush LaSelle, Jabil Additive’s senior director of AM. “Across our factories, we will spend in excess of $100 million [annually] on various forms.”

Besides reducing these costs, Auburn Hills wanted to use 3D printing to speed up the time required to introduce customers’ new products. An early order of business was training because the facility’s personnel had no AM experience and no additional staff was hired for the project. LaSelle’s group did the majority of the training, assisted by representatives of the firms that made the 3D printers installed at the facility.

According to LaSelle, AM implementation went smoothly. During the training process, he and his colleagues encountered no employees seemingly set in their ways and unwilling to try new things. In addition, he noted that Auburn Hills benefited from “some stubbing of our toes” in earlier implementations.

“We found that what does not work is buying expensive equipment and putting it into a lab,” LaSelle said. Engineers and operators won’t use it because they don’t want to tie up expensive equipment with what he calls “tinkering.”

Instead, Auburn Hills started with relatively small and inexpensive desktop printers. “Putting in desktop units helped [personnel] to be comfortable and to start familiarizing themselves with the technology,” LaSelle said.

So did the initial instructions they got from their trainers, who told them not to print anything for the factory. “We said, ‘Print some tchotchkes for the kids. Take some time off from your day and just experiment and get comfortable with it,’” LaSelle recalled.

The results validated this approach. Within a month of the first desktop printers arriving at Auburn Hills, and weeks earlier than anticipated, 3D-printed parts were being integrated into the manufacturing line, LaSelle noted. Today, Auburn Hills reports that AM has slashed the time to produce custom tools and fixtures by 80% and has reduced tooling costs by 30% for many of its programs.

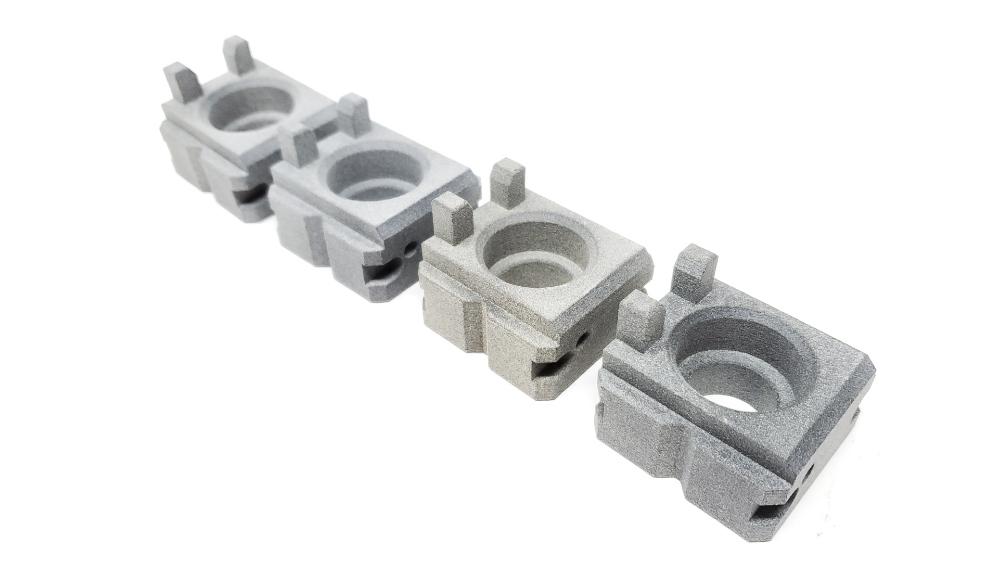

The success of AM at Auburn Hills has led to expansion of the program. While at the outset just two people were involved in 3D printing activities, today that number ranges from 15 to 20 and includes engineers, technicians, and operations personnel. In addition, LaSelle noted, the filament-based desktop machines have been joined by nylon powder-bed systems more suitable for batch and serial production.

Most of what’s printed on-site is still tooling and fixturing for the production line. But now, LaSelle added, AM is also used for some end-use parts, as well as prototyping and bridge manufacturing for new product introductions.

Not for Everything

Besides grasping the capabilities of 3D printing, shops new to the process need to understand its limitations.

“In my opinion, the additive manufacturing industry has been greatly harmed over the last 10 years by the large machinery OEMs [telling] shops they should use additive manufacturing for everything,” DeWys said. “So people would try using it for things it isn’t built or intended for, and it would fail horrifically.”

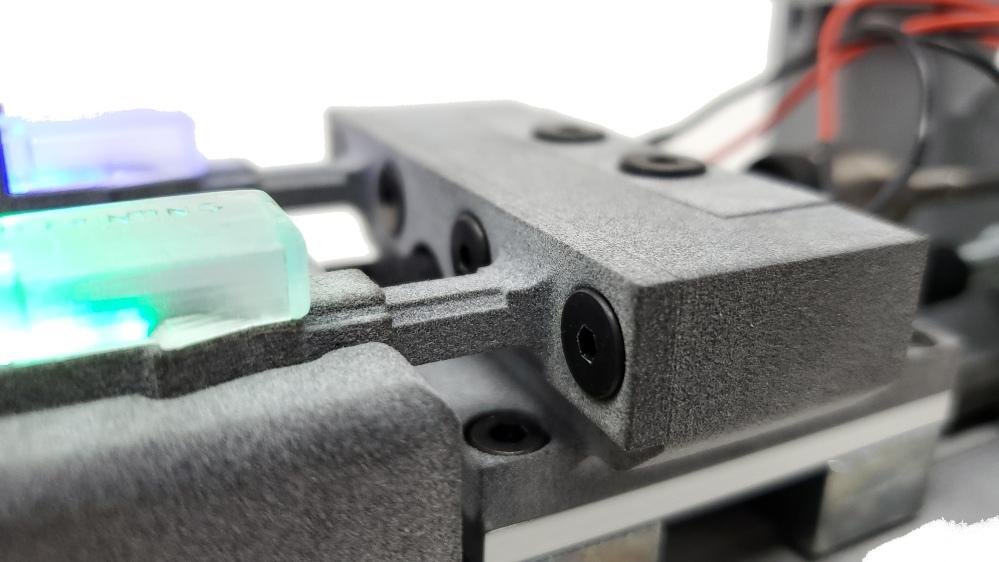

Forerunner 3D-printed this pogo pin nest for an automated end-of-line tester machine. Forerunner 3D Printing

According to DeWys, current 3D printing technologies usually aren’t good options for producing larger structures. “When customers come to me with a massive part, if it is not something that can be easily broken up into sections for printing and then assembled, I will tell them [not] to force it onto a printer that can do it that big, get suboptimal results, and pay an arm and a leg for something that is probably not what they want,” he said.

In addition, he noted, shops must be aware of the accuracy limitations of current 3D printing systems. For parts that can be held in the palm of your hand, AM can probably hold a tolerance of ±0.005 in. or maybe slightly better, he said. While this is fine for many of his customers, tolerances sometimes need to be much tighter. In those cases, he believes the best option may be a hybrid approach in which a polymer part is printed and then certain portions that require higher accuracy are machined in a secondary operation.

So rather than a manufacturing be-all and end-all, 3D printing should be thought of as just one more tool in a shop’s toolbox.

“It is not going to replace traditional machining systems or the skill set of a talented machinist,” Burd said. “It is going to augment those to allow a facility to be more productive.”

About the Author

William Leventon

(609) 926-6447

About the Publication

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI