- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Staying overnight in a Cold War-era missile silo near Roswell, Part 2

Exploring more of the bunker and learning what it took to build and fabricate the silo

- By Darla Welton and Josh Welton

- June 27, 2021

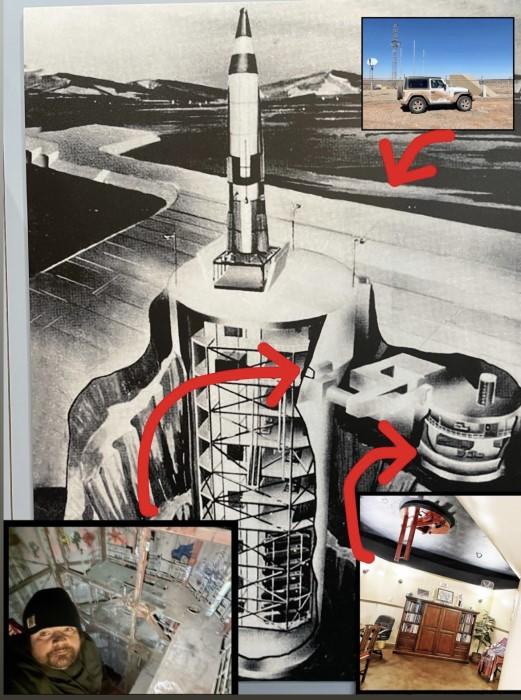

While road tripping through New Mexico, Josh and Darla Welton stopped in Roswell to stay overnight in a Cold War-era missile silo, operated by Gary Baker. In Part 2 of their two-part blog about the experience, they explore more of the bunker and learn what it took to build and fabricate the silo. Images: Darla and Josh Welton

After Day 1 of our Cold War-era missile silo overnighter, we woke the following morning with a bit of a history-lesson hangover. Even though Josh and I were a little groggy, we were excited to continue our adventure near Roswell, N.M.

We slept in the upper level of the bunker, where our host, Gary Baker, has created a cozy living space with a full bath and kitchen. Originally that level served as the kitchen, mess, toilet, medical supply, and power distribution room for the Atlas F missile site. An escape hatch to the surface stands out on the rounded ceiling.

Gary, of course, is bright-eyed and peppy as he leads us downstairs to the lower level of the bunker. It’s worth noting that Gary recently had a hip replacement, but he still climbs all of these stairs like a champ. The lower level of the bunker boasts taller ceilings than the upper level, and it originally housed the launch control center. Gary retrieved the control counsel from the bottom of the silo, where the demo team trashed it during the demilitarization process.

These Cold War-era bunkers are essentially concrete bubbles suspended from the large column in the center. Designed to “float” on massive springs in the event of a blast, the bunkers’ engineering and fabrication of the suspension is a marvel. The Atlas F complex was the first of the "hardened" missile silo structures. The concrete used was mixed with an epoxy-based resin to provide a substantial increase in strength.

When combined with an estimated 600 tons of steel rebar, this provided a structure capable of more than 200 lbs. per square inch of overpressure – roughly equivalent to a 500-MPH wind. This made the Atlas F complex one of the most robust structures ever built by man. And as we mentioned in Part 1, the five-person LCC squadron was protected when the missiles accidentally detonated.

Crossing the utility tunnel toward the missile silo, Gary mentions that “the original blast door to the silo was constructed of 4,000 lbs. of manganese and designed to withstand 5,000 degrees before it would break down.”

Before opening the door, Gary adds, “Now, one of the greatest engineering design failures, I believe, is what you are about to see in this silo. Who in God’s name was going to put a diesel engine that gives off hydrocarbons in here? I mean, have you ever known of a diesel engine that doesn’t bleed? But put it on top of 300,000 gal. of locks in a 50-ft.-tall, 12-ft.-diameter giant thermos on level eight of the silo? Sometimes I just want to slap myself because I can’t believe this was the best that we had!”

We step inside.

What remains of the 186-ft. underground silo is something to behold. Gazing upon its current glory, marked with graffiti from years of abandonment, we lean over the platform edge, trying to glimpse the bottom. (While the space was dimly lit during our visit, Gary has since installed LED lights for better viewing.) We take note of the areas where some substantial plasma cutters had demilitarized the silo. You can’t help but notice the 6-ft.-thick doors in the ceiling that would open via one of the most heavy-duty hydraulic systems ever designed.

Why Were These Sites Abandoned?

From atlasmissilesilo.com:

Layout of the Cold War-era Atlas F missile silo complex where the Weltons partked, slept, and explored.

“The volatile nature of liquid-fueled rockets made the Atlas complexes a challenge to manage and maintain. Several accidents caused the complete loss and closure of the sites involved. Advancements in solid-fuel rocket technology made the Atlas liquid-fueled missile obsolete by the time the sites were activated, and by mid-1965, all of the Atlas missile sites had been decommissioned and closed. The Atlas rocket was removed from the sites and stored by the Air Force at Norton AFB, located east of Los Angeles. They were later used by the Air Force and NASA as satellite and research and development launch vehicles. Equipment that the Air Force deemed classified or re-useable elsewhere was removed. Most of the land properties were then returned to previous landowners or given to a local government entity.”

Gary adds: “The Air Force tried to come up with options for repurposing the silos. They thought perhaps they could be used as storage facilities for Minuteman ones, but Boeing said that to retrofit and reuse the sites, it would have cost even more to refurbish them. Nobody had commercial power out here in the 1960s, and they sent each of the site’s two 500-kW diesel generators over to Vietnam. Then there was the biggest dilemma of the physical basing modes themselves. What in the world could they or anyone else do with a 400,000-lb. elevator with 1 million lbs. of counterweight designed to lift a 400,000-lb. missile to the surface?”

Gary continues, “These nuclear missile silos cost the 2021 equivalent of $107 million each in 1960. And after only three years, the government shut down the program and moved on to the Titan missile program. They ordered the sites to be demilitarized and publicly sold them for $1,700 each.”

Yes, you read that right. Only $1,700.

A Missile Silo Dream

In the 1970s Gary attended the New Mexico Military Institute in Roswell. He had a group of friends who would play in and around the missile silos.

“We had a club. To become a member of the club, we took you to a silo that had been completely scrapped – not a bolt left on the concrete walls and no water in her. You had to rappel to the bottom, sign your name on the wall, and use a pair of ascenders and come all the way up. Then you were in the club.

“A bunch of us at school were adrenaline junkies. We lived for danger, and all had ended up with great careers. We did Airborne, we did the Rangers, the Special Forces. We all did something fun and got to kick ass and take names.”

Gary’s father and grandfather helped build several silos in Alaska and the northwest U.S. Missile silos were often part of their dinner conversations while he was growing up.Holding such fond memories of these sites, Gary dreamed of owning and renovating one. So about 25 years ago, he made that dream come true.

Now having owned three sites himself and having helped countless other silo owners renovate and source parts, Gary became an expert, even taking on a job with the Army Corp of Engineers to put his knowledge to use.

“I once turned down $1 million for this site. I know what she’s worth. And what am I gonna do? Be bored? I mean, no offense, I live in Roswell, which is not a great metropolis,” says Gary.

And he is keeping himself busy with these sizable projects.

Keeping up With Gary and Planning Your Missile Silo Adventure

Capturing photos to convey the size of the missile silo was nearly impossible, so we recommend visiting Gary and the silo yourself. And soon you’ll be able to rappel down to the bottom of the silo to sign your name and become a member of “the club.” You can also learn more from the Atlas F Missile Fact Sheet.

Gary maintains a vast collection of missile silo memorabilia, much of which you can view on his website, Instagram, and YouTube.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscriptionAbout the Authors

Josh Welton

Owner, Brown Dog Welding

(586) 258-8255

- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI