Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Rebuilding the might of the domestic metal supply chain

Leaders of metals-related associations have advice on how to restore U.S. manufacturing

- By Dan Davis

- June 3, 2021

- Article

- Metals/Materials

The Section 232 tariffs on imported steel and aluminum have given steelmakers in the U.S. a chance to solidify their market position and invest in modernization of their production facilities. During that time, however, steel prices have risen to record highs, frustrating many metal fabricators and manufacturers. Despite customer frustrations, the leaders representing the domestic steel and aluminum producers say that they still need the tariffs in place to protect them from the Chinese-produced metals that are heavily subsidized by the Chinese government. Alextov/iStock/Getty Images Plus

As metal fabricators try to stay on top of increased business opportunities, they might find it hard to believe that metals manufacturing is nowhere near the levels it was in the years leading up to the Great Recession. Things can—and perhaps should—be even busier than they are now.

The Metals Service Center Institute (MSCI), Rolling Meadows, Ill., tracks monthly shipments from its member distributor companies in Canada and the U.S. According to its Metals Activity Report, aluminum shipments in October 2020 were 25% below their 2006 levels, and steel shipments were down 40%. That’s a huge chunk of manufacturing activity that simply doesn’t exist today.

What has created this situation, and what can be done to create demand for metals so that shipment levels reach those of the mid-2000s? Phil Bell, president, Steel Manufacturers Association, Washington, D.C.; Kevin Dempsey, president/CEO, American Iron and Steel Institute; Washington, D.C.; Tom Dobbins, president/CEO, The Aluminum Association, Arlington, Va.; Bob Weidner, president/CEO, MSCI; and Ed Youdell, president/CEO, Fabricators & Manufacturers Association Intl., Elgin, Ill., gathered for a virtual roundtable in April to share their points of view and plans to strengthen the country’s metal-producing base and the rest of the supply chain. The good news: Everyone’s bullish on the future.

An edited version of the roundtable discussion follows.

The FABRICATOR: What has occurred over the years to cause such a drop in metals shipments?

Bob Weidner, Metals Service Center Institute: We commissioned Keybridge Public Policy Economists [in Washington, D.C.] to try to figure out why this is happening. Because even before COVID, if you go back to the end of 2019, metal service center shipments were materially below 2006 peaks.

We had several hypotheses, which Keybridge has tested and recently completed two projects for us. They’ve given presentations to our members. Data-based analysis shows two things contributed to this decline.

First and foremost, there has been the offshoring to China. Since China was admitted into the World Trade Organization, we have seen the erosion of our manufacturing base to China. That has played a huge role in service center shipments’ declining.

The second study points to a not-so-obvious reason. With the residential housing market, we basically are coming off a decade of little activity. Household formations were occurring much later than they had been started historically. This trend has both a direct and an indirect role in the falloff in service center steel and aluminum shipments as well.

Outside of a possible metal beam or metal roofing, you don’t think of residential construction as consuming steel and aluminum. But when you think of all the support and the indirect steel and aluminum that goes into those homes, it’s really mind-boggling. You have appliances, metal fixtures, casings, and HVAC. You have the carpenters, electricians, and plumbers with their trucks and all of their metal equipment. It goes on and on.

Metals Service Center Institute (MSCI), aluminum shipments in October 2020 were 25% below their 2006 levels, and steel shipments were down 40%. Taitai6769/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Ed Youdell, Fabricators & Manufacturers Association Intl.: I was just reading a study that showed, I think, since 2009 we’ve “underbuilt” about 2 million homes. So it really does support what Bob is saying. Since the Great Recession, there’s just a lack of housing stock in the market. And we’re seeing it now in high housing prices as people look to move, wanting to leave cities and get out into the suburbs. There just isn’t any place for them to go.

FAB: What can be done to get industry on the path to grow the market so more metal is being produced, shipped, and consumed?

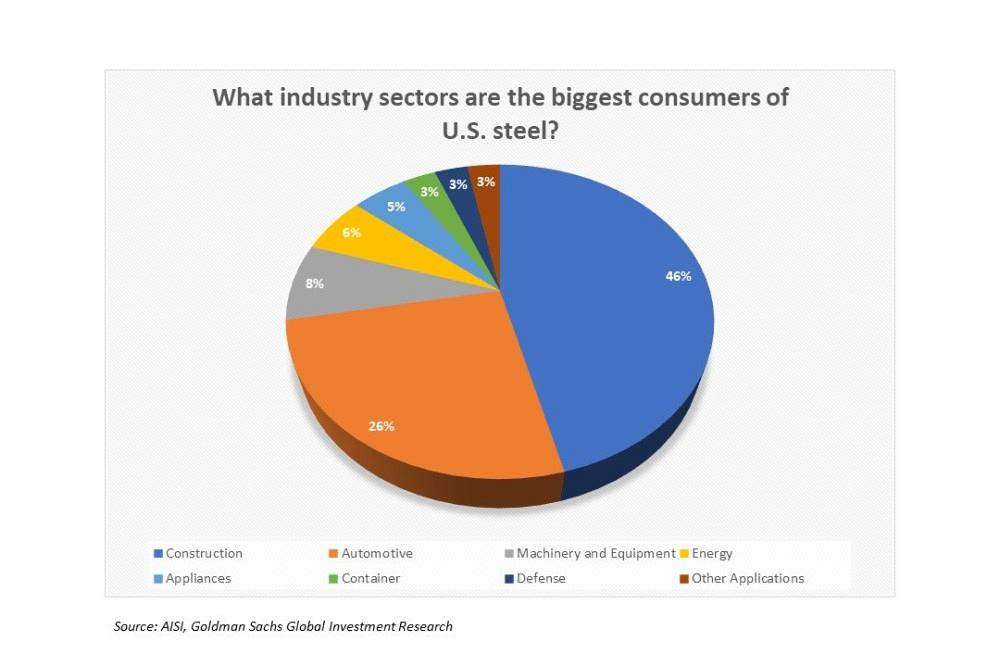

Phil Bell, Steel Manufacturers Association: There are a couple of things that can be done right away. One of them is that we have domestic procurement preferences in a long-term, well-funded infrastructure investment program. We need to be using steel that’s made by Americans for Americans, not only in residential construction, but in all of our infrastructure.

The domestic steel industry has invested heavily in new, efficient capacity to meet any uptick in demand. I think with strong “Buy America(n)” and other procurement references, we can do that right away. And from an overarching point of view, we just need to approve a well-funded infrastructure investment that focuses on steel-intensive and traditional infrastructure.

Tom Dobbins, The Aluminum Association: I’ll build off what Phil and Bob said. Addressing the trade issues is absolutely critical. China is subsidizing their aluminum production and particularly semifabricated goods. So they have curtailed their export of primary aluminum material and now incentivize export of their semifabricated goods. As for growing the U.S. market, we need to invest in infrastructure and do what’s necessary to continue to have housing starts go up. We can do all of these things to grow our market, but if that demand is filled by dumped steel or aluminum, then American workers are not going to get the benefit of our work.

We as a country need to work with our allies and isolate China. We need to keep them from exporting subsidized goods and dumping them in our markets. We’re now even seeing China dumping into our allies’ markets, and the displaced metal ends up coming into the U.S. We have to watch out not only for China directly, but indirectly from our allies with market economies.

What we’re seeing now is we’ve been effective with the 301 and 232 tariffs. The Aluminum Association also is undertaking several antidumping and countervailing duty cases against China and others. As a result, the Chinese are now dumping into Europe. So they’re displacing European aluminum, and that’s coming into our markets. We’re hopeful that if the Europeans are successful in keeping the Chinese out of their markets and then, working with us, diplomatically isolate the Chinese, it’s going to be positive for the U.S. and European markets and U.S. steel and aluminum fabrication.

Kevin Dempsey, American Iron and Steel Institute: If I could just follow on what Tom and Phil said, I agree with both of them in terms of solutions. Certainly, an expansive infrastructure bill helps. Domestic procurement preferences will be beneficial to the metals industry, helping to bring increased demand in the infrastructure areas.

But I do think that to go after the problem of the offshoring of so much U.S. manufacturing to China over the last decade, we really have to step up the enforcement of our trade laws. As Tom said, this is a problem that not only directly involves the U.S. and China, but also impacts other countries. China is increasingly subsidizing the development of their steel industry in China and also funding the expansion of Chinese steel producers into other countries, such as those in Southeast Asia. There’s a major Chinese stainless steel producer—Tsingshan—working out of Indonesia now because the country has raw materials, such as nickel, that you need for making stainless steel. That steelmaking development basically has been funded by the Chinese government through its Belt and Road Initiative. This has been done in cooperation with the Indonesian government, which has banned the export of the raw material nickel so that no one else around the world can get that. Investments like that have created a huge, additional distortion that feeds through the metals industry on the stainless steel side.

I think the United States and the European Union have both woken up to that problem, and there’s a World Trade Organization case that was started by the EU challenging this new Indonesian trade restriction. We’re working hard to get the U.S. government to work with the EU in opposing that. That’s the type of thing we do need to do: not only step up the enforcement of our own trade laws, but coordinate with our allies around the world to make sure we’re all enforcing the trade laws in the U.S., the EU, and parts of Asia to take on the challenge presented by China.

Based on steel consumption patterns in the U.S., a major infrastructure bill would be very beneficial to the steelmakers, but could continue to stress material availability for other steel consumers.

FAB: Obviously the tariffs on aluminum and steel have garnered quite a bit of attention since they have gone into effect. What have they allowed the domestic metals companies to do, and what does that mean for metals consumers?

Bell: During this period, what you’ve seen is the 232 tariffs have done a lot to accomplish the goals of increasing capacity utilization, saving jobs, and also encouraging investment in the domestic steel industry. What we’ve seen over the last four years is what I would call a modernization and electrification of the domestic steel industry.

There is a report out by the Economic Policy Institute that cited more than $15.7 billion of investment is either announced, underway, or near completion. What we’re going to have as a result of those investments are new, modern, clean, and efficient steel mills.

Also the 232 tariffs are working for the country. It’s helping the aluminum industry as well. The tariffs are also doing something that a lot of people didn’t even foresee: They’re actually making America greener. One of the surprising effects of the tariffs was that they have dramatically reduced the importation of foreign steel made in high CO2-emitting factories from countries in Asia, EU, and the Middle East. The tariffs have done a great job of reducing CO2 emissions. That in and of itself ought to be a reason for the Biden administration to continue to carefully evaluate them and leave them in place.

Dobbins: I’d add that most Chinese aluminum is produced with coal-fired power, but unfortunately it hasn’t curtailed them at all. The primary aluminum production that we have here in the U.S. and North America is obviously low-carbon, with aluminum from Canada being smelted with hydropower. But we still see China rolling on unabated.

We do see in the market that low-carbon aluminum is being marketed and becoming attractive to customers, which is helping the Western countries that smelt and fabricate aluminum.

Dempsey: I agree totally with what’s been said about the significant new investment in the industry. As Phil mentioned, as a result of the tariffs, the Economic Policy Institute cited $15.7 billion as being invested back into steelmaking. That study also noted that the steel industry in the U.S. has devoted another $5.9 billion towards industry restructuring and consolidation. We’ve seen some major changes just in the last year with Cleveland-Cliffs, an iron ore producer that acquired the assets of two different steelmakers in the U.S.—AK Steel and the U.S. assets of ArcelorMittal. It has consolidated into a large, much more efficient operation that does everything from making the iron ore all the way down to the finished steel product. At the same time, U. S. Steel acquired Big River Steel, a new electric arc furnace producer.

So we’ve seen significant consolidation. What that will result in is increased efficiencies in the U.S. steel industry that, on top of the new investments, will help make us more competitive and create a cleaner industry

It should be noted that on a per-ton basis, the Chinese steel industry emits 2.5 times more CO2 per ton of steel produced than steel made in the U.S. And if you look globally at the total emissions of CO2 from the steel industry, China accounts for about 64% of global steel emissions; the U.S. is 2%.

We are a clean industry in terms of steel production, and that’s both because of our big investments in electric arc furnace technology and advances in how integrated steel producers are using a pelletized iron, which is much lower emitting than the iron used overseas.

Also we’re investing in new ways of making the iron that goes into steelmaking. A new facility just opened by Cleveland-Cliffs in Toledo, Ohio, that will be making hot-briquetted iron, called HBI, using natural gas, and the process will produce iron that can be fed into steel mills and will have a much lower carbon-emissions footprint than traditional iron units. That brand-new facility was designed so that as hydrogen becomes more available in commercial quantities, the facility can switch over about 70% of its natural gas usage to hydrogen with only very minor modifications.

So we’re building an industry that is ready to make additional improvements moving forward to reduce our carbon emissions. That really is due in large part to the opportunities presented by the 232 tariffs. They have allowed the steel industry to embark on a path to be much more competitive and much greener going forward.

Weidner: From our perspective, I can tell you that we testified on the 232s about excess Chinese steel capacity in front of U.S. Trade Representative, and we testified on excess Chinese aluminum capacity in front of the International Trade Commission. We supported the tariffs on what I call upstream—the producers. Also, keep in mind that 30% of the members of MSCI are mills, so we supported the tariffs. But we went one step further than my colleagues on the producing side. We said that the government also should have looked at imposing a 20% tariff on the fabricated metal parts. We need both a healthy source of domestic supply as well as a healthy source of domestic demand.

The Chinese are smart enough to figure out that they can get around tariffs on a steel coil, an aluminum sheet, or whatever substrate it is by just subsidizing the downstream metal users—the parts manufacturers—and flood the market with fabricated metal parts that are artificially priced based on nonmarket-based economics.

So we did say that the government should have looked at some kind of tariffs to protect companies using metal; and, by the way, a lot of service centers are doing fabricating as well. But the tariff on fabricated metal products didn’t come about.

I think the other thing that we have to keep in mind here is the pandemic has changed some thinking as it relates to China. For a long time now, many big OEMs had a fixation with Chinese manufacturing. The problem is that none of them factored a pandemic risk into their business calculations. Now you have all of these supply chains that were dependent upon suppliers thousands of miles away, many in nonmarket economies. I do believe that there will be a movement toward shorter supply chains, more regional supply chains, and supply chains less dependent upon China.

And I would like to add one more thought, and this is my personal opinion, not the opinion of MSCI. I believe it’s very sad that we’ve allowed off-shoring to a communist country where democratic principles are not valued, nor is there a commitment to reducing carbon emissions like there is here.

I can’t reiterate enough the importance of having both a healthy North American metals supply base and a healthy North American source of demand.

Dobbins: And as Bob mentioned, we must think of this from the perspective of North America. We have to be careful about product coming in from Mexico. We pushed Mexican authorities to incorporate aluminum import monitoring into their programs, and they have so far failed to do so.

We have anecdotal and other evidence that subsidized Chinese aluminum is coming into Mexico and then being used in products. Obviously, that’s a way for the Chinese manufacturers to backdoor products into the North American market. As associations, we need to collectively ensure that isn’t happening.

Youdell: For the metal fabricating industry, our concern obviously would be the dumping of the metal parts. If in the process of securing the domestic steel industry we hurt the ultimate end customer for that material by, for example, letting imported fabricated metal products in through the back door, we really haven’t accomplished much. That’s a concern of fabricators.

We also recognize the opportunity associated with localized supply chains that has come to the forefront because of the pandemic. It makes sense for major OEMs to be close to metal fabricators to shorten that supply time and to help OEMs get to market quicker.

Our metal fabricators are incredibly focused on automation and technology to support OEMs. So it’s important that we have strong North American steel producers, strong distributors, and strong metal fabricators and manufacturers.

Now it makes a great deal of sense to focus on stengthening production. Right now, the availability of material is a growth restraint for fabricators and manufacturers. The more material that we can get online quickly, the quicker we’ll see those prices come down. That would be a great relief to metal fabricators.

FAB: How long do you think the Section 232 tariffs should be in place?

Bell: I don’t have a crystal ball, so I can’t tell you how long the 232 tariffs will be in effect. But here’s what we do know. The 232 tariffs need to stay in effect while the Biden administration does a comprehensive review of their impact on domestic and international steel markets. Also, you want to be able to negotiate from a position of strength when considering removing the tariffs. To be in a position of strength, the tariffs need to be in place.

Another thing that I will share with you is the new capacity that’s coming online should result in a stabilization in the price increases that we have seen in recent months. The new capacity is going to not only displace unfairly traded imports, but also displace inefficient capacity and allow for more product offerings from these companies that are making these enormous investments.

What we’ve also seen is a market, at least for steel producers, that’s actually been pretty resilient. The pandemic caused a lot of volatility in demand, supply chains, and overall availability, but we’ve seen manufacturing actually be a bellwether industry throughout the pandemic. It’s going strong. The automakers have come back after they shut down last March because of COVID. This momentum should continue as you’ll see more availability and prices become rationalized in the ensuing months as more capacity comes online.

Dobbins: I agree with Phil. The only thing that I would add is that we’re looking at 232 exemptions being granted for aluminum from all the various countries and markets where we see Chinese aluminum and other subsidized aluminum possibly penetrating. So again, if the Europeans are successful in keeping out subsidized Chinese aluminum, then we could be more open to granting an exemption to the Europe Union. I presume steel feels the same way. We’re more than happy to compete on a level playing field, but at this point, that playing field is not level.

Another issue that comes into play are the retaliatory tariffs, which have been the case in Europe since the 232 tariffs were put into place. So echoing Phil’s point, you need to negotiate from a position of strength, because retaliatory tariffs and other tariffs need to come down and need to be fair and in alignment with our tariffs on products from Europe. And we can’t absorb metal that has been displaced by dumped Chinese aluminum.

Dempsey: I’ll just add that I don’t know when the tariffs are going to change, but I do know that we need some progress on addressing the underlying cause that led to the steel and aluminum tariffs. And that’s the global steel overcapacity problem that is being driven by China. It affects the entire world. That really should be the focus right now.

If you lifted the tariffs, at least on steel, and you haven’t dealt with the global overcapacity problems, a new surge of imports would come into the U.S. You’d have all of this excess supply. We’d see a flood back into the U.S. similar to what happened in the 1990s after the Asian financial crisis when the demand shock in other parts of the world led to a flood of steel into the U.S. from all around the world.

We have a global problem. It needs a global solution. I absolutely agree with Tom’s point that we want a level playing field, and that means getting other governments out of the business of subsidizing their own production of metals, whether it’s steel or aluminum. I think that’s at the heart of the problem in the U.S. We have a free market where industry competes, where companies build new facilities, and old facilities go out of business. We let the market decide, and the government is there only to ensure that the rules needed for the market to operate fairly are enforced. If other countries adopted that same approach, we would solve a lot of these problems in terms of our capacity. These other countries’ governments either subsidize new capacity or don’t allow inefficient capacity to leave the market.

Steel mills go out of business in the U.S., but unfortunately in a lot of parts of the world, that never happens, no matter how inefficient those plants are. Foreign governments step in to keep their people employed for social and political reasons even when the plants cannot survive without subsidies. That’s what needs to really change.

Weidner: The other thing, too, that we have to remember is that China is a nonmarket economy, plain and simple. They need to be held accountable.

When I took this job 20 years ago, the Chinese steel industry was about the size of the U.S., give or take 10 million to 20 million tons, right? We were about 125 million tons; they were about 140 million tons. The last time that they reported statistics, which I think was 2019, they were at more than 900 million tons.

It’s the same on aluminum capacity. They made a decision 20 years ago that they were going to target certain industries. Primary aluminum and steel were targeted, and they planned to dominate. We haven’t heard much lately about China’s 2025 Plan, a national strategic plan. But you know that they are going to target several downstream manufacturing industries like they targeted primary aluminum and primary steel 20 years ago. The Chinese are going to come in, and they’re going to subsidize those industries. It’s going to continue to distort the world’s markets for aerospace, construction and agricultural equipment, electric vehicles, and many more targeted manufacturing industries because China is a nonmarket economy.

It’s going to distort market forces for those downstream metal products, causing problems for distributors, fabricators, and manufacturers. Eventually it will back up to the producers as well because there will be an erosion of the domestic manufacturing base.

So China has said just what they plan to do. The one thing about the Chinese, when they say they’re going to do something, they eventually do. It may take a century to get it done, but they aren’t going to change their mind. So again, and nobody writes about this, I would encourage everyone reading this column to research China’s 2025 industrial plan.

The downstream manufacturers should be as concerned as all of us have been. As an example, look at the stainless steel industry. A large percentage of the world’s stainless steel producers are Chinese. North America needs to manufacture products, and the playing field needs to be level. When the Chinese violate or don’t comply with their WTO commitments, they need to be held accountable.

FAB: Do you think the domestic metals community has made technology advancements that enable it to thrive amidst global competition?

Youdell: I’ll start with the fabricator’s perspective. Our guys love clean air and clean water. Our guys also have been very innovative just in terms of how they produce parts more efficiently from an energy standpoint. They are running their operations more efficiently—saving money, controlling costs, and being more cost-competitive.

Some are even committing to the trend of zero waste to landfill. You see that in U.S. manufacturing, where no waste is coming out of the factory. They are recycling, reusing things in different ways, and being smarter about their manufacturing processes. That’s really an opportunity for the metals industry. We need to get back to promoting the use of metal because of its recyclability and its efficiency of production. Metal needs to be a material of choice for North American manufacturing.

Dobbins: I wanted to build off what Ed said in that the key to maintaining U.S. supremacy in manufacturing is staying ahead of the curve in technology. There will always be other countries that have a lower cost basis for labor, and for us to compete, we have to be technological leaders.

One of the frustrations that I have witnessed from a high level is that the U.S. provides basic research to the entire world. Our universities are by far premier in terms of basic research and technology readiness levels, but these universities really don’t do anything to commercialize the majority of the research. We give it to the world. Our competitors in countries like Germany, Japan, and China take that basic research and move it through Technology Readiness Levels 4-7, otherwise known as the “Valley of Death” on the way to commercialization.

The Obama administration created the advanced manufacturing institutes to try and help us compete against the Fraunhofer Institutes of the world and other programs that exist in other countries and regions to advance manufacturing technology. Unfortunately, I don’t think that those institutes have lived up to the promise that was made to us. As an industry, we need to step in and be more proactive in working with those institutions and with our federal laboratories to really accelerate the transition of technology from basic research to commercially ready, to make our economy more competitive when compared to other low-cost economies.

FAB: Given everything that we’ve talked about, are you bullish on the future of metals production and processing in North America?

Dempsey: I am very bullish on the future of the metals industry in the U.S. I think we are at the head of the line in terms of developing the newest technology like HBI, and we’re the leaders in the world in terms of an advanced recycling infrastructure. That’s a real benefit for us because that gives us those key raw materials to continue to produce metal products very efficiently.

We’re also leaders in terms of moving to a greener forms of energy, whether that’s using natural gas or looking for opportunities with hydrogen. You know, a lot of the newer steel mills being built by Nucor and others are going to be fueled entirely by renewable energy. I think that type of leadership is going to be critical for the industry going forward. That leadership in terms of environmental stewardship will pay off big time for us.

Bell: One thing I’ll say to piggyback on Kevin’s remarks is that the metals industry has shown how resilient it is. It is a critical and essential industry. It’s helped this nation work its way out of the COVID-19 pandemic by delivering goods to critical industries and to end users.

And it’s also a wonderful and glorious industry. You’ll never hear people saying we don’t pay living wages or don’t provide good benefits. You’ll never hear people say we don't embrace innovation. You'll never hear people saying we don’t try to operate our facilities as safely as we can. So I'm absolutely bullish and optimistic about the industry. I’m just glad to be a part of it.

Weidner: I agree with everything that’s already been said. I will add that both steel and aluminum are more recyclable than almost any product. I don’t know of a single member in the industry who doesn’t respect the planet. We’ve demonstrated that by the investments that have been made both from the mills and the service centers.

The other point that I want to make is that this pandemic, which has been horrific, also has forced people to rethink their supply chains. There is a shift that is occurring now, and the focus is on localization of supply chains. I do believe they are going to structurally become shorter and more regional.

This country never again should be caught where we have completely outsourced manufacturing of something like Tylenol to China. We can’t get caught short on things like PPE, which we desperately needed in the early days of the pandemic. That should never be allowed to happen again.

We have to manufacture things here. We’re not going to be a service economy. As the recovery has demonstrated, manufacturing is leading the way. It’s not the consumer, which will play a big role down the line. But manufacturing is here to stay. I am more optimistic now than I’ve ever been in almost 40 years when I first joined Inland Steel.

Dobbins: I’d just add that the people in this industry help to make it special. They are extremely dedicated.

The leadership in this industry deserves to be recognized as well. We’ll all keep working to help our members grow and ensure that they can compete fairly in what they do. If we can do that, the industry is going to be wildly successful.

Youdell: I’ll just say that we think our best days are ahead for metal fabricators. Once we get steel prices down from these historic highs, it will be even better. Because as we know, these high prices are a constraint to growth.

Job shop owners are a unique breed of person. They’re all about innovation, flexibility, and competitiveness. So knowing the people that I know, I’m excited to be a part of this industry. The people who run these shops care about the people that work there, stress safety in their operations, and are always looking for ways to be more competitive and grow their companies. I believe our best days are ahead of us.

About the Author

Dan Davis

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8281

Dan Davis is editor-in-chief of The Fabricator, the industry's most widely circulated metal fabricating magazine, and its sister publications, The Tube & Pipe Journal and The Welder. He has been with the publications since April 2002.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI