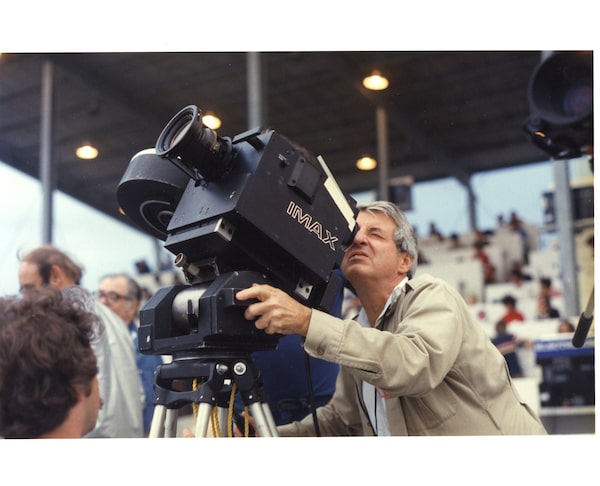

Graeme Ferguson on location filming a space shuttle launch for the 1982 IMAX film Hail Columbia!Roger Scruggs/IMAX

They thought big. Fifty-four years ago, filmmakers Graeme Ferguson and Roman Kroitor and novice producer Robert Kerr, stoked by the popularity of their recent experiments at Montreal’s Expo 67, teamed up with Mr. Ferguson and Mr. Kerr’s high-school pal, engineer William Shaw, to invent a type of giant-screen motion picture that would plunge the audience deep into its world.

Today, their creation, Imax (“maximum image,” abbreviated and inverted), has become synonymous with spectacle. It is a mainstay of science centres, museums and multiplexes; its superior technology is beloved of such Hollywood heavy hitters as director Christopher Nolan; and it continues to play its historic role as the cinematic chronicler of NASA’s space missions.

Mr. Ferguson, meanwhile, became synonymous with Imax. Of those four “big thinkers,” he was the one who shaped the company the most profoundly in its first 25 years. He created the signature Imax film, 1971′s North of Superior, produced its string of landmark space-shuttle documentaries in the 1980s and nineties, served as its president for two decades and held the unofficial position of its artistic conscience for even longer.

“Graeme was the most passionate of the founders on an ongoing basis,” Imax Corporation’s CEO, Richard Gelfond, said. “Long after he was retired, I would call him to consult with him.”

Mr. Ferguson, who died on May 8 at Lake of Bays, Ont., at the age of 91, was the embodiment of Imax’s high standards and continuous innovation. He was a perfectionist who toiled over every frame of his films and he possessed the relentlessly analytical mind of the born problem-solver. He had the sort of mania for detail that led him to keep an ongoing pocket journal – in countless tiny notebooks, crammed with minuscule handwriting – throughout his life.

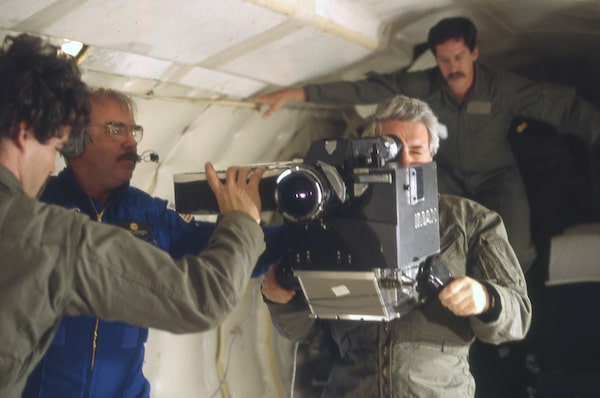

Graeme Ferguson tests an IMAZ camera in zero-gravity on NASA's KC135 (which astronauts have called the 'Vomit Comet').NASA/Imax

“The history of his life and every film is in them,” said Barbara Kerr, a former Imax editor and close friend. “He was still writing in them as long as he could hold a mechanical pencil.”

For those who knew him, there was no question as to what fuelled that passion for precision.

“Curiosity drives passion and he always had it,” said retired Canadian astronaut Roberta Bondar, who was front and centre in Mr. Ferguson’s 1994 NASA doc Destiny in Space.

“My father was an explorer,” added his son, director Munro Ferguson. He wanted to know and understand the world, from its oceans to outer space, but also bring his discoveries to the screen as never before. “He was all about exploring film as a medium, inventing new ways to tell stories.”

Ivan Graeme Ferguson was born on Oct. 7, 1929, in Toronto to schoolteachers Frank and Grace Ferguson, who gave him the educational bent that would later inform his Imax films. As a kid he made home movies and, a self-described geek, was particularly fascinated by how the process worked. Growing up in Galt (now part of Cambridge), Ont., he attended Galt Collegiate Institute, where he met Mr. Kerr and Mr. Shaw, who shared his interests in mechanics and inventing.

Following high school, he enrolled at the University of Toronto to study political science and economics, but also got involved in the university’s film society, helping them shoot a spoof of avant-garde films. That experience led to a summer apprenticeship at the Ottawa-based National Film Board in 1950, where he met fellow student Mr. Kroitor. Their lives would later entwine personally as well as professionally, with Mr. Kroitor marrying Mr. Ferguson’s sister Janet.

Back in Toronto, Mr. Ferguson had the encounter that he later said changed his life. American experimental filmmaker and dancer Maya Deren – one of the legendary avant-gardists he’d parodied with the film society – had come to town to give workshops and shoot a new project. Mr. Ferguson ended up assisting her, then falling hard for her. Although their romance was brief, they remained friends and she urged him to pursue a career in film.

After graduation in 1952, Mr. Ferguson did just that. He worked as an assistant to Swedish director Arne Sucksdorff on a documentary shot in India, supplied the cinéma-vérité camerawork for the Oscar-nominated short doc Rooftops of New York and dabbled in quirky features, including an improvised satire called The Virgin President starring members of Chicago’s The Second City. He met his first wife while shooting a film in Alaska. They were married in 1959 and settled in New York, where Betty Ferguson became an experimental filmmaker as well and the couple had two children, Munro and Allison.

Mr. Ferguson was lured back to Canada when the organizers of Expo 67 asked him to do a film for the Montreal world’s fair. To produce it, he called on Mr. Kerr, who by then was the mayor of Galt. Mr. Kerr gamely agreed and the result was the documentary Polar Life, shot both in the Arctic and Antarctica, for the “Man the Explorer” pavilion. Mr. Kroitor, meanwhile, was making his own Expo flick, In the Labyrinth, for the NFB.

Both movies used multiple screens and a mosaic of images to create immersive experiences that wowed the crowds at Expo. They were a pain to co-ordinate, however, involving a battery of projectors that had to be kept in sync. One afternoon, Mr. Ferguson and Mr. Kroitor hashed over the problem at the latter’s house in Montreal and came up with a solution: a single projector that fed 70 mm film horizontally – as opposed to the standard vertical feed – to allow for an image nine times larger than the average 35 mm movie, which would fill a vast screen.

To build the projector, Mr. Ferguson and Mr. Kerr turned to Mr. Shaw, then a product manager for sporting-goods manufacturer CCM. Using a “rolling loop” mechanism patented by Australian inventor Ronald Jones, Mr. Shaw developed the prototype Imax projector, which was used to screen the inaugural Imax film, Mr. Kroitor’s Tiger Child, at the 1970 Osaka Expo in Japan.

Shortly after that, the budding Imax company found its first permanent venue when it was commissioned by Toronto’s new Ontario Place theme park to provide a short documentary for the colossal screen of its Cinesphere theatre. North of Superior, a stunning (and largely aerial) portrait of the Northern Ontario wilderness, was produced, directed and shot by Mr. Ferguson. A thrilling success, it would continue to be screened regularly at the Cinesphere for decades, introducing generations of Ontario schoolchildren to the Imax experience.

By the 1970s, the Ferguson family had settled on a farm outside Galt, fondly remembered by Ms. Kerr, Robert Kerr’s daughter, as a “hippie haven” forever filled with visiting artists and filmmakers. But the Fergusons’ marriage was ending in acrimony. Following their divorce, Betty Ferguson launched what became a precedent-setting corporate lawsuit over shares she had held in Imax. “It was quite a painful period,” Munro Ferguson, who was a teenager at the time, recalled; although he said his father remained at arm’s length from the case.

Graeme Ferguson shooting a scene for the 1971 IMAX film, North of Superior. Ronald Lautore, the assistant cameraman, uses a 'space blanket' to protect Ferguson (and the only IMAX camera) from the heat.Imax

Mr. Ferguson, meanwhile, began a relationship with young broadcaster Phyllis Wilson, who had done location work for North of Superior. The two eventually married in 1982 and she became part of the Imax team on its next adventure, the space-shuttle films.

Although the NASA brass were initially leery of allowing Imax cameras aboard its spacecraft – or having their astronauts trained to operate them – the first film to do so, 1985′s The Dream is Alive, made them converts. By the time that the team – including Mr. Ferguson’s long-time collaborator, writer-editor Toni Myers – came to work with Ms. Bondar and her crewmates on the space shuttle Discovery in 1992, they were wildly popular.

“When the astronauts found out Imax was going to be on the flight, they were crawling all over each other to get assigned,” Ms. Bondar recalled. She remembered Mr. Ferguson as the cool-headed sage of the Imax team, who could patiently tease out any problem – as well as an unabashed Canadian determined to get CanCon into the films whenever possible. For the Discovery trip, captured in Destiny in Space, he asked the astronauts to try to photograph the Belcher Islands as they flew over Hudson Bay. “When the time came, they called me up to the flight deck and said I had to help them, they didn’t know what to look for,” Ms. Bondar said, laughing. “Graeme represented our country and I felt it gave me cachet,” she added. “It was a time when I felt very proud of being a Canadian.”

Mr. Ferguson kept up the drive to innovate, leading the development of a 3D Imax camera, showcased in both its space and undersea films, that anticipated Hollywood’s digital 3D boom. Under his watch, Imax also introduced its planetarium-friendly Dome system. But despite such efforts as the 1991 concert film The Rolling Stones: Live at the Max, the company had difficulty breaking out of the educational niche and into the mainstream.

That changed in the early 1990s, when U.S. entrepreneurs Mr. Gelfond and Bradley Wechsler bought Imax, took it public and steered it in a more commercial direction. It meant scaling down the format for regular cinemas and converting to cost-saving digital – compromises that some purists decried. Mr. Gelfond, however, said that Mr. Ferguson approved. “He liked very much what we were doing with the company and urged us to continue to take it to new frontiers.”

Today, Imax is a thriving corporation with 1,652 screens in 84 countries and territories. Its global box office in 2019, its best year to date, was US$1.05-billion. The company won an Academy Award for its technological achievements in 1996. Mr. Ferguson himself amassed all kinds of accolades, ranging from the NASA astronauts’ Silver Snoopy for his service to the space program to his appointment to the Order of Canada.

Mr. Ferguson spent his later years with Phyllis at Norway Point on Lake of Bays in Muskoka, where they owned a sprawling stone cottage. Mr. Kerr and Mr. Shaw also had cottages on the lake and all four of the Imax founders remained good friends throughout their lives. Mr. Shaw died in 2002, Mr. Kerr in 2010 and Mr. Kroitor in 2012. Their families and colleagues, including the late Ms. Myers and Imax executive Jennifer Rae, became part of one big, close-knit clan. “People would refer to us as ‘the Imax family’ without irony,” Ms. Kerr said.

In 2020, Mr. Ferguson was diagnosed with throat cancer and was battling it when Phyllis died of a heart attack in March of this year. His daughter, Allison, a nurse, tended to him at Norway Point in his last weeks. Despite the double blow, he maintained his usual practical outlook and even a cheery disposition. “He felt that he’d lived such a long and productive life and done all the things he wanted to do,” Munro Ferguson said. “He could look back without regret.”

Mr. Ferguson leaves his children, Munro and Allison Ferguson; four grandchildren; one great-grandchild; as well as his siblings, Janet Kroitor, Mary Hooper and Bill Ferguson.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.