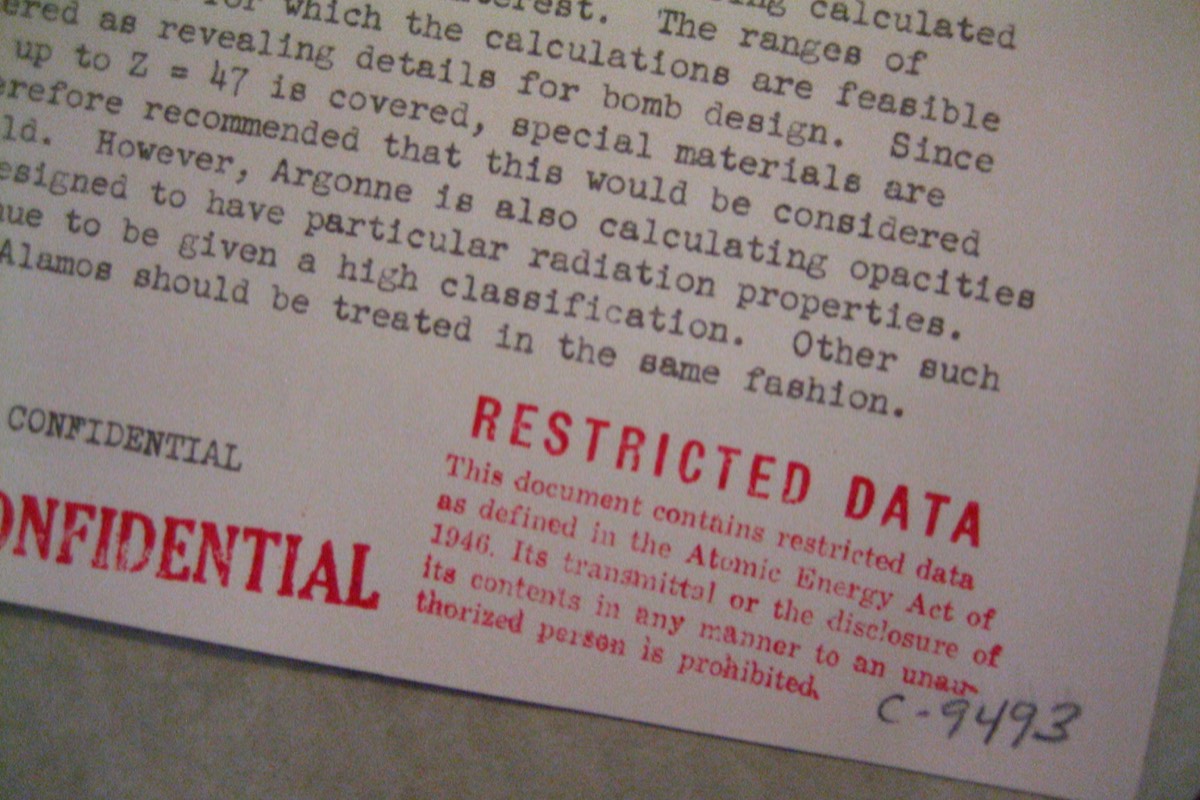

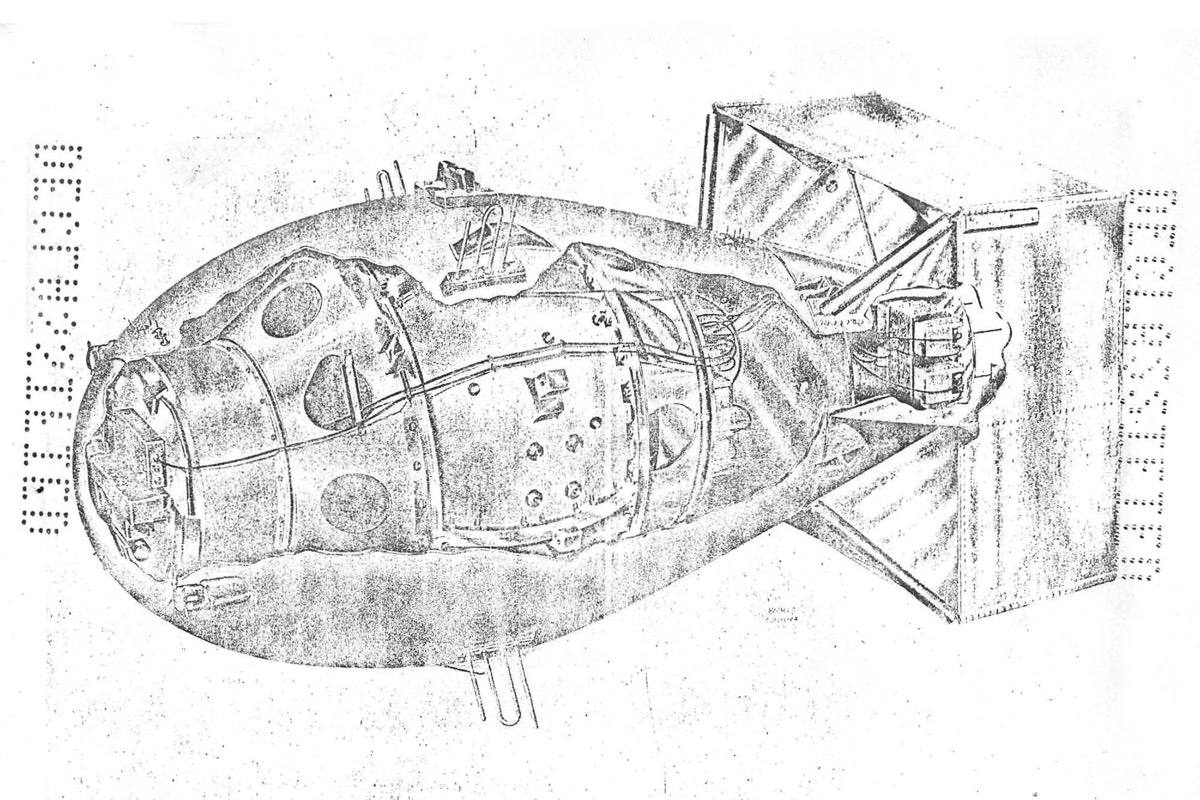

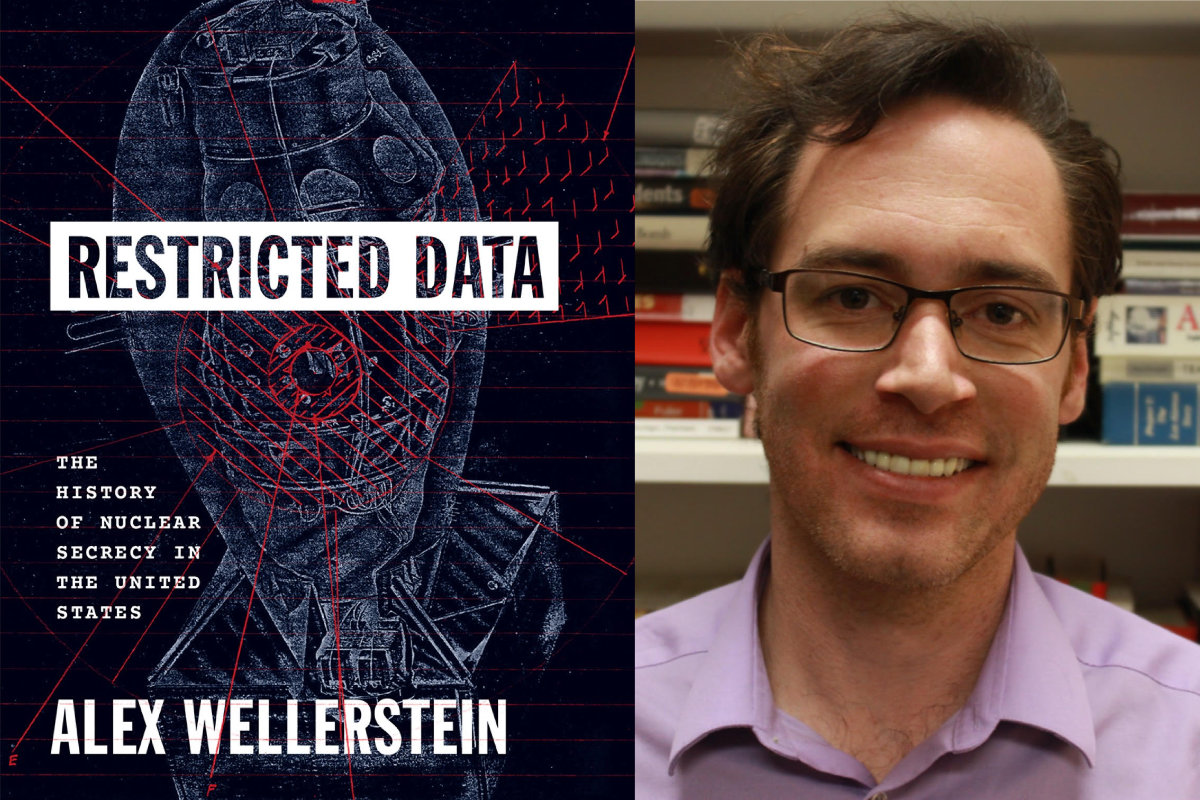

The revolutionary discovery of nuclear fission in December 1938 helped launch the Atomic Age, bringing with it a unique need for secrecy regarding the scientific and technical underpinnings of nuclear weapons. This secrecy evolved into a special category of proscribed information, dubbed "Restricted Data," which is still in place today. Historian Alex Wellerstein spent over 10 years researching various aspects of nuclear secrecy, and his first book, Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States (University of Chicago Press), was released earlier this month.

Wellerstein is a historian of science at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey, where his research centers on the history of nuclear weapons and nuclear history. (Fun fact: he served as a historical consultant on the short-lived TV series Manhattan.) A self-described "dedicated archive rat," Wellerstein maintains several homemade databases to keep track of all the digitized files he has accumulated over the years from official, private, and personal archives. The bits that don't find their way into academic papers typically end up as items on his blog, Restricted Data, where he also maintains the NUKEMAP, an interactive tool that enables users to model the impact of various types of nuclear weapons on the geographical location of their choice.

The scope of Wellerstein's thought-provoking book spans the scientific origins of the atomic bomb in the late 1930s all the way through the early 21st century. Each chapter chronicles a key shift in how the US approach to nuclear secrecy gradually evolved over the ensuing decades—and how it still shapes our thinking about nuclear weapons and secrecy today.

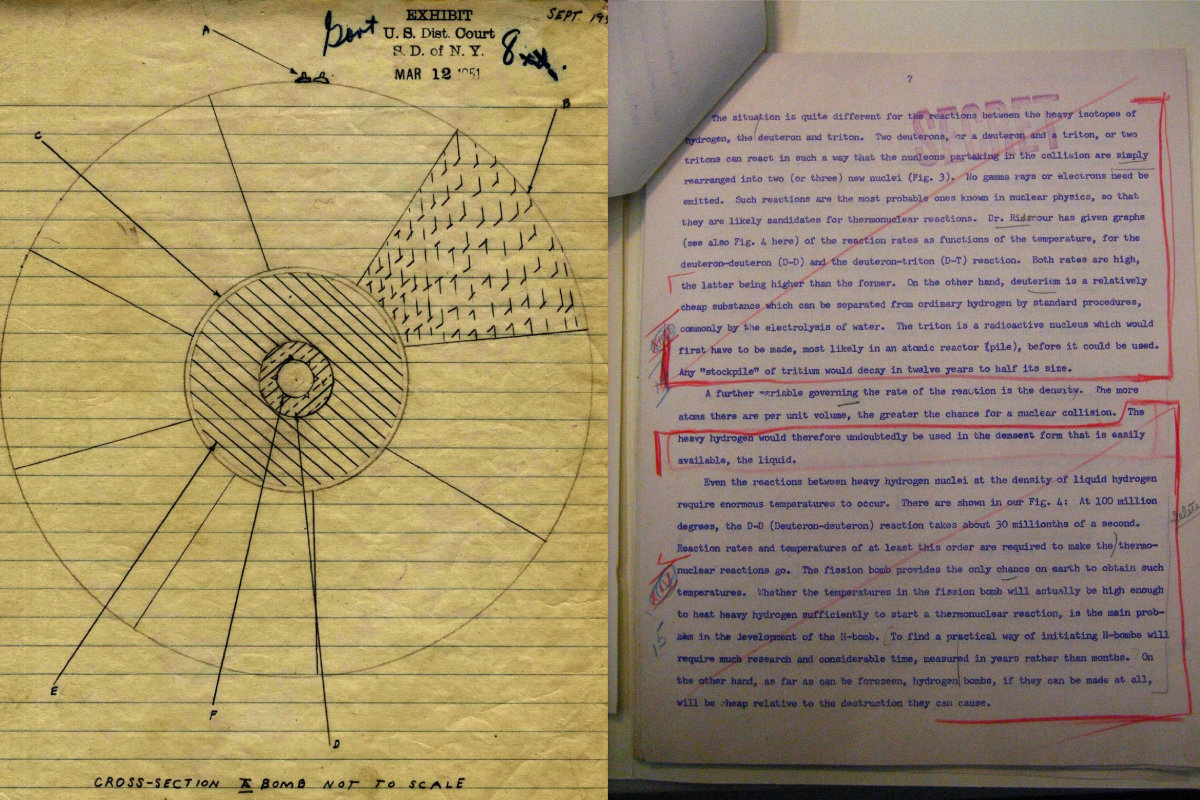

Along the way, we meet such pivotal figures as Vannevar Bush and James Conant, as well as famous Manhattan Project scientists like Robert Oppenheimer, embedded journalist William Laurence, and notorious Soviet spies Klaus Fuchs and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Wellerstein delves into the establishment (and eventual dissolution) of the post-war Atomic Energy Commission, the emergence of the Cold War, and how attempts to reform the system failed (due in part to partisan politics), leaving the US with an outdated nuclear secrecy policy that is arguably not especially effective.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...