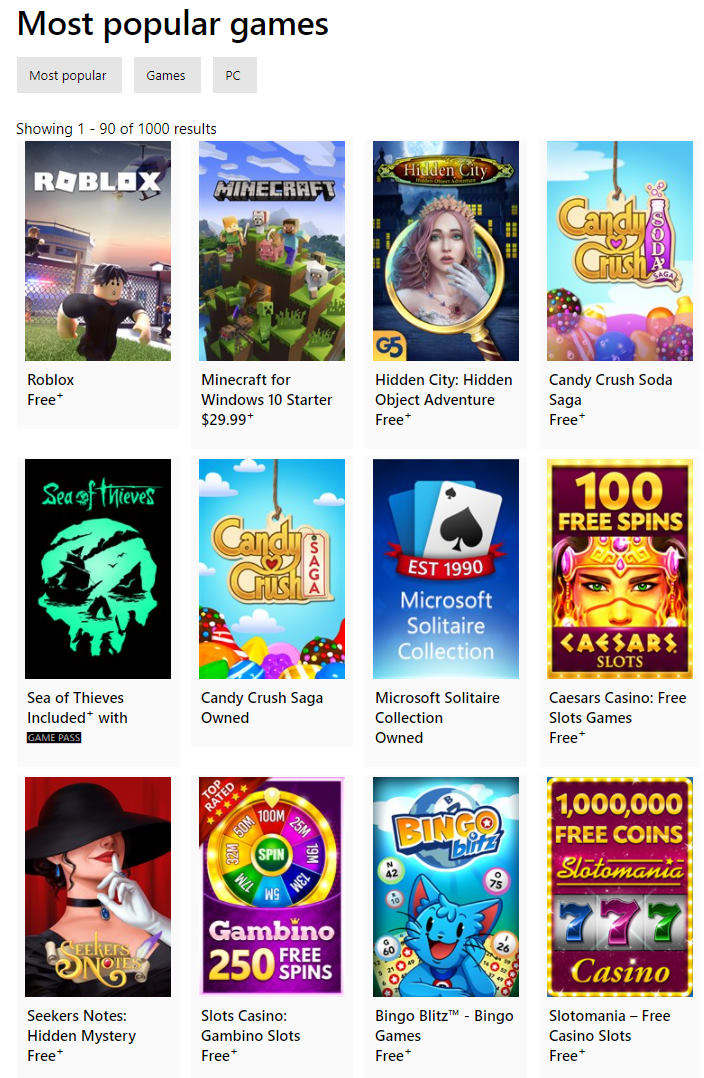

Microsoft is lowering the revenue cut it takes on games sold through its Microsoft Store on PCs from 30 percent to 12 percent, marking a new front in its uphill battle to take on competing game distribution platforms like Steam and the Epic Games Store.

"Having a clear, no-strings-attached revenue share means developers can bring more games to more players and find greater commercial success from doing so," Microsoft Head of Game Creator Experience and Ecosystem Sarah Bond wrote in an announcement post. "All this to help reduce friction, increase the financial opportunity, and let game developers do what they love: make games."

The new rate, which goes into effect on August 1, seemingly applies to games specifically and not to the general entertainment and utility apps that are also sold on the Microsoft Store platform, based on the language in the announcement. The change also doesn't apply to game development across the Xbox console ecosystem, where Microsoft will still take a 30 percent cut (as do other major console makers).

Stiff competition

On consoles, of course, Microsoft relies on that 30 percent cut to make up for losses incurred on the sale of hardware. And on the Xbox, Microsoft is in the enviable position of being in full control of the only legitimate method of distributing downloadable games to customers (a similar situation to the one causing legal headaches for Apple and its iOS App Store).

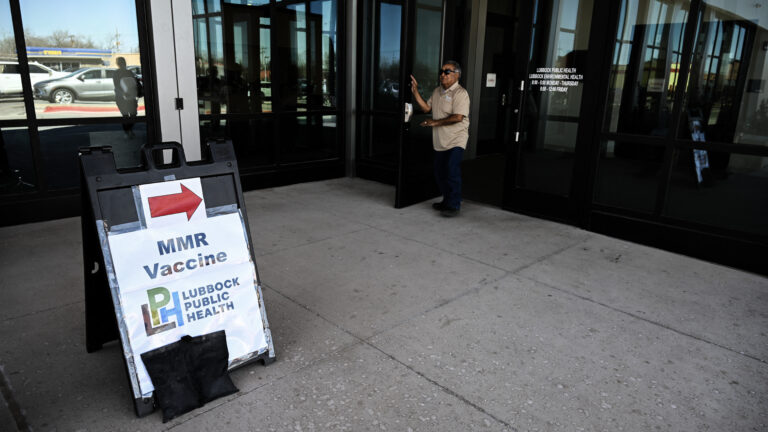

On the PC, by contrast, Microsoft's downloadable game store faces stiff competition from multiple competing platforms—as well as the ancient practice of gamers just downloading EXE files. And while there are some big-name titles currently available through the Microsoft Store, the platform's selection of games is currently dominated by a lot of lowest-common-denominator shovelware.

Microsoft's revenue-sharing move comes over two years after the Epic Game Store launched on PC with its own 12 percent revenue cut and could put additional pressure on Steam to lower its standard 30 percent cut (though that number comes down a bit for best-sellers and doesn't apply to Steam codes sold via third-party stores). Then again, Epic has only clawed its way to a roughly 15 percent share of the PC gaming marketplace (as estimated by Epic CEO Tim Sweeney last June) by throwing huge sums of money at developers for timed exclusives and free game giveaways.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...