There are many things songwriter and producer Jim Steinman could be compared to: He was as subtle as a flying mallet; he made Bruce Springsteen, even at his most melodramatic, seem restrained; he was, as has been rightfully noted tenfold since his passing last week, a purveyor of pop excess, of lyrical excess, of production excess. But there was also a lot of humor in his work and a love of the pop and rock send-up. Steinman’s work wasn’t about excess per se. It was about starting at excess and piling on more excess from there. The tools he used to achieve that were an odd mix of classical grandiosity, Spectorian walls of sound, cartoony sound effects, and (sometimes) tongue-in-cheek lyrics. Squint a bit and you can place him in the company of downtown-Manhattan oddities such as the early Bette Midler, proffering a semi-ironic pastiche of genres and camping up the past, lightly, but with new and modern emotional intents. In Steinman’s case, the excess was part of the fun, and he found melodies and chord changes that gave it all a foundation. At his best, the humor and his natural talents came together — most often in the work of Meat Loaf but in some other ’80s pop artists as well — to create ineffable moments of pop and rock grandeur.

Steinman died on April 19 at his home in Connecticut at the age of 73. According to the New York Times, he had suffered a stroke a few years ago.

He was a visionary, if slightly ridiculous, composer and lyricist, and in time became a wildly successful producer with significant pop and rock hits to his credit on both the album and singles charts. He was discovered, in a way, when he was still in college. During his senior year at Amherst, where he focused on theater, he was one of the creators of a stage concoction dubbed The Dream Engine. It was a large-scale work involving a narrator called “The Historian,” and included songs like “Inspirational Hymn: The God Game” and “Liberation Through Pleasure (Ride a Cock Horse).” Steinman wrote of its concept in an early draft of the project: “The work is, in essence, a rock opera, despite the fact that it is not all music … Ideally, I would like the work to unite the ‘music-drama’ structure of Wagner’s opera with the more immediate political and social bite of Brecht-Weill’s Mahagonny.”

Steinman’s show was three hours long, had “tons of nudity,” and caught the attention of local police. But Joe Papp, the influential leader of the Public Theater, came to see the shows and signed him up during the intermission — surrounded by a cast of nude performers, as Steinman described it. “He saw no difference between Shakespeare and Hair,” Steinman would recall of the producer years later. “It was all theater. I grew up with opera and rock and roll and didn’t see anything different [either]. It was all sensation. Papp became my surrogate dad.” The Dream Engine didn’t make it to the stage in New York, but Steinman worked with Papp there for seven years. It was a time when once and future participants in The Rocky Horror Show, the National Lampoon tours, SNL, and many other soon-to-be-successful endeavors bumped elbows downtown.

In 1973, a singer named Michael Aday was in the cast of Rocky Horror, then still a downtown stage musical. Aday, playing the role of doomed motorcycle boy Eddie, sported a beefy physique and a handsome but somewhat porcine face that made the moniker Meat Loaf a befitting (albeit unflattering) stage name. Steinman was still at the Public Theater working on a musical called More Than You Deserve, which is set in Vietnam during the war and was reportedly about the relationship between an impotent base commander and a female reporter, who is gang-raped and turns into a nymphomaniac; the cast included Fred Gwynne, Ron Silver, and Mary Beth Hurt, and featured Paul Shaffer as musical director. Meat Loaf came in to audition, and Steinman saw something in him immediately. “He was a big huge actor,” Steinman would recall. “I found someone who could sing my music the way I envisioned it. He embodied what I was trying to get at theatrically.” Meat Loaf had a piercing — but friendly and instantly recognizable — high tenor that Steinman’s ambitious and overwrought songs perfectly encompassed. Meat Loaf joined the cast in a minor role but ended up bring down the house each night with the show’s title song. “More than You Deserve” remains one of Steinman’s funniest concoctions. As with many of his conceptions, it begins at a not-insignificant level of intensity both musically and lyrically and drives up the emotions from there. From the first verse, the singer is in a state of high dudgeon, having seen his girlfriend “makin’ love to one of my best friends.” In the second verse, she’s with “two of my best friends” … and in the third, “a group of my best friends,” as the singer’s blood pressure rises each step of the way. (The video remains a kitschy hoot.)

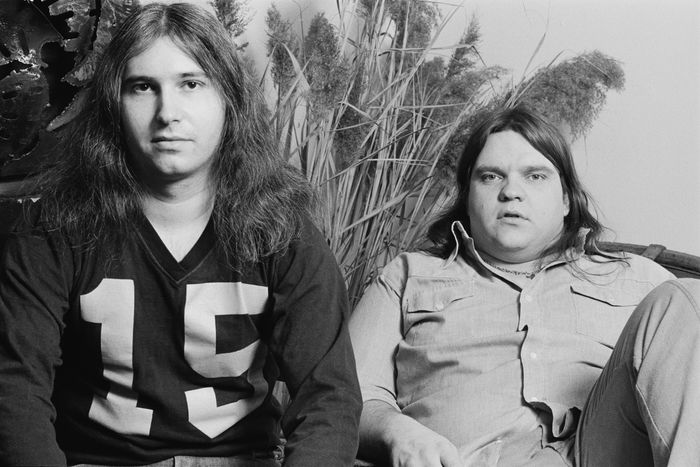

The pair joined the National Lampoon road show and began to collaborate, working out the songs that would make up Meat Loaf’s first, triumphant album. By this time in the mid-’70s, Springsteen, on his first trio of releases, had made the rock world safe for melodrama with songs like “Jungleland.” Still, Steinman’s were too much even by those standards, and the pair’s ideas and auditions were famously rejected by virtually all of the major labels of the time over a two-year period. Through a complex chain of circumstances, they ended up recording with producer Todd Rundgren at Albert Grossman’s Bearsville Studios in Woodstock before they had a record deal. Rundgren oversaw the crystalline, if unsubtle, dynamics that would mark the songs that became 1977’s sensational Bat Out of Hell. (Steinman would later say the album deserved to be credited as a collaboration among the three of them.) In time, a small label called Cleveland International took them on and eventually persuaded CBS, the parent company of Columbia and Epic at the time, to distribute it.

Sales started slow. At that point, Meat Loaf had appeared in the film version of Rocky Horror, a raging cult hit across America through the 1970s, and so he had a small base of fans. But that wasn’t enough to make the record anything like a hit. Then some filmed performances of songs from the record, first in the U.K. and then in America, kick-started sales. Most memorably, a hulking, sweaty, almost feverish Meat Loaf delivered over-the-top performances of “All Revved Up and No Place To Go” and “Two Out of Three Ain’t Bad” in March 1978 on Saturday Night Live, invited by his friend John Belushi. Bat out of Hell started selling, and never stopped.

Steinman’s songwriting shtick was set here. He took random idioms and clichés (“bat out of hell,” “two out of three ain’t bad,” “for cryin’ out loud”) and gave them twists — sometimes gentle, sometime ironic — and then developed epic song structures around them. He built onto the songs everything they could hold, and occasionally more. Lyrically, his songs were just as full of excess: demons flying down the highway at night, that sort of thing, along with odd bits of wordplay that the overabundance of the arrangements and Meat Loaf’s engaging voice somehow managed to make digestible. It’s evident in “You Took the Words Right Out of My Mouth,” whose lyric continues, “It must have been while you were kissing me.” Another lyrical gem: “There ain’t no coupe de ville / Hiding at the bottom of a Cracker Jack box.”

The album was also notable for the length of Steinman’s songs. While long and self-indulgent compositions were the rule in the progressive-rock world, and mainstream rock occasionally proffered multi-minute epics like “Dream On,” no one had ever seen a straightforward rock album with extravagant theater tunes like this: The average song length on Bat Out of Hell was nearly seven minutes.

Steinman’s greatest triumph, if that is what it is, remains “Paradise by the Dashboard Light,” a junk-opera epic of teenage lust from the album’s second side. Here, “paradise” — uh, spoiler — is a woman’s naked body; over some nine minutes, Meat Loaf delivers an appropriately hysterical performance of Steinman’s perfervid story, which involves the woman stopping a makeout session and extracting a promise from the singer to love her till the end of time if they have sex. It takes a full seven minutes of increasingly deranged singing (arranged with a mad genius by Rundgren) before she gets her promise — at which time Meat Loaf lands the sophomoric punch line:

And now I’m prayin’ for the end of time

To hurry up and arrive

’Cause if I have to spend another minute with you

I don’t think that I can really survive.

The album was a major hit that year — and continues to be. It has sold about 14 million copies in the U.S. and has been a perennial seller worldwide. (Though the claim on its Wikipedia page that it has sold 50 million copies is vastly overstated. According to chartmasters.org, which collects and analyzes industry data worldwide in a more sober fashion, the album has sold 27 million copies in total internationally.) The album’s confused beginnings and vast success also accordingly left many lawsuits in its wake, not least between Meat Loaf and Steinman. In interviews, incidentally, Rundgren has said he had negotiated for royalty points on the album, which paid off handsomely; he’s said he was sure that he has made more money off Bat Out of Hell than anyone else.

After Bat Out of Hell, Meat Loaf found himself beset by myriad problems, some not of his own making. Steinman tried to cope with his music partner’s health, drug, and management conflicts for a few years before giving in and recording his own solo album. Bad for Good, released in 1981, demonstrated clearly that he was not a rock star. He lacked the voice to deliver his own songs, and the accompanying videos displayed him as a posturing rock-and-roll lunkhead with little sense of any theatrical distance in his inhabiting of the role. Three years later, Meat Loaf pieced his life back together and the pair managed a formal follow-up to Bat Out of Hell. The result, 1981’s Dead Ringer, became one of the biggest relative flops in the history of the record business; it never even made the Top 40 album chart. The rest of the 1980s saw the pair’s fortunes as a duo get ever-more tangled, contentious, and self-sabotaging. In one version of the story, Meat Loaf wasn’t allowed to use a couple of promising Steinman songs for his dispiritingly titled 1983 album, Midnight at the Lost and Found. It became another flop.

Steinman, however, was finding his groove as a songwriter and began a steady career as a pop hitmaker for other artists, from the Sisters of Mercy to Céline Dion. Along the way, he created several more hilarious, hysterical pop megaworks, culminating in one outlandish week of success in which two Steinman songs occupied the No. 1 and No. 2 positions on the Billboard “Hot 100”: “Total Eclipse of the Heart,” by Bonnie Tyler, which spent four weeks at No. 1, and “Making Love Out of Nothing at All,” by Air Supply, which sat at No. 2 beneath it. “Total Eclipse,” driven by Steinman’s own appropriately galactic production and ludicrous touches like the angelic “turn around, bright eyes” call-and-response, became one of the biggest hits of the era. (These, incidentally, are the two songs Meat Loaf was supposedly not allowed to use on Midnight at the Lost and Found.)

Meat Loaf’s career seemed over, but finally, at the height of the MTV era, with the careers of everyone from Aerosmith to Steve Winwood revitalized, a known brand like his could not be left at the side of the road anymore. Steinman and the singer reunited for an absurd work with the appropriately Spinal Tap–ish title of 1993’s Bat Out of Hell II: Back Into Hell, which Steinman wrote and produced. CBS, back then still a powerful presence in the music industry, marketed the album with ferocity and a seemingly bottomless budget. Among other things, the pair was granted a seven-minute video for the song “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That),” directed by Michael Bay, a filmmaker who shared Steinman’s visions of excess. (Note that no fewer than five minutes had been trimmed from the album version of the song.) But there was also something like subtlety in other tracks, like “Objects in the Rear View Mirror May Appear Closer Than They Are,” if subtlety is a word that can be used in reference to a song that goes on for ten full minutes. MTV went all-in with CBS and embraced the over-the-top videos; Bat Out of Hell II was a huge hit, selling 12 million copies worldwide in the nearly three decades since.

That album forever vindicated Steinman’s work. He had one last pop triumph, “It’s All Coming Back to Me Now,” a No. 2 hit for Dion. Otherwise, he busied himself with all manner of other production work and a litany of random things successful people do in the last decades of their lives: a collaboration with Andrew Lloyd Webber, a never-staged production called Garbo — The Musical, and what was said to be a heavy-metal version of The Nutcracker. Along the way were the expected, intermittent trips back to the Bat Out of Hell well, from a stage musical to his contributing some songs to a Desmond Child–produced Bat Out of Hell III in 2006. Eventually, he and Meat Loaf got into a legal dispute over the title Bat Out of Hell.

Finally, around that same time, he got to see his beloved The Dream Engine staged in New York. More than a decade later, in 2019, Bat Out of Hell: The Musical made it to New York too. The show, said the Times, had “its engine gunned, its wheels mostly spinning, its tailpipe jammed with whatever passes for a plot.” It was the culmination of a classic rock-and-roll story in its own right — the arc from overnight sensation to jukebox musical, you might say, or, alternatively, the one about the precocious theater kid who meets a beefy guy with a voice quasi operatic enough to match his grandiose tongue-in-cheek visions — visions that resonated, for a time, with a generation of teenagers and stay in their memory to this day.