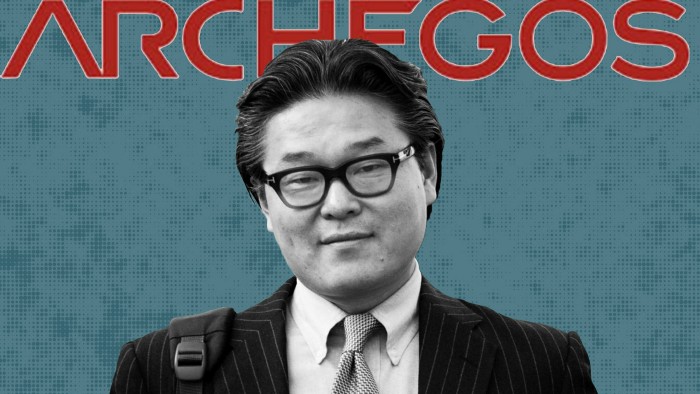

‘He never struck me as a big risk-taker’: Bill Hwang’s big bet blows up

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In early 2013, Bill Hwang was barred from the US investment business. Authorities alleged that, as part of an insider-trading scheme, his Tiger Asia Management hedge fund had violated promises it made to some of the world’s most powerful investment banks.

Hwang, a pastor’s son who moved from South Korea to the US as a teenager, quickly bounced back. Steeping himself in scripture, he set up a family office — Archegos Capital Management — and eventually built up trading positions running into the tens of billions of dollars with Wall Street banks, including some of the ones his old firm was accused of cheating.

In recent days Hwang’s world has unravelled. Banks dumped more than $20bn of stock tied to his derivatives trades, counterparties warned of billions of dollars in potential losses and associates wondered how a quiet, abstentious family man who gave much of his money to Christian causes had wound up as the central figure in a colossal Wall Street mess.

“He never struck me as a big risk-taker,” said a Korean businessman who worked with Hwang in New York. “But when you hear the news you wonder what happened that he built such a massive fortune and now it’s being unwound so quickly.”

Hwang’s rise was remarkable. When he arrived in the US, he reportedly did not speak English. In a talk given to Sandy Cove Ministries in Maryland last year, Hwang said he was so out of his element that he did not know how to call emergency services when his father died at the age of 50.

Nevertheless, Hwang made it to the University of California, where he studied economics before earning an MBA at Carnegie Mellon.

He began his business career at Hyundai Securities and the now-defunct investment bank Peregrine before cutting his teeth as a trader at Julian Robertson’s legendary hedge fund Tiger Management.

He joined the firm in 1996, according to his LinkedIn profile, and focused his stock-picking efforts on South Korea and parts of east Asia, reporting to Robertson, according to one person who worked with Hwang.

Robertson encouraged his protégé to launch his own firm, prompting Hwang to declare himself an “accidental investor”. He struck out on his own in 2001 with Tiger Asia, a fund seeded by his former boss, and emerged as one of Robertson’s most successful “Tiger Cubs”.

“Bill’s story is a real Cinderella story. He is a devout Christian. He doesn’t even drink beer and has donated a lot of money to churches,” said a close friend of Hwang. “Only months after he moved from Peregrine to Tiger, Peregrine went bankrupt. Everyone who knew him at that time said Bill was blessed and protected by God.”

Hwang, who lives with his family in the leafy suburbs outside of Manhattan, in Tenafly, New Jersey, remains close to Robertson. After the travails of Archegos emerged, Robertson wrote to Hwang, who is now in his 50s, to express his concern, according to a person with knowledge of the matter.

“I’m just very sad about it,” Robertson told Bloomberg news service. “I’m a great fan of Bill, and it could probably happen to anyone.”

But Hwang had been in trouble before.

In 2012 Hwang had shut down Tiger Asia, which managed more than $5bn at its peak, after it was hit with the insider-trading allegations. He entered a plea of guilty on behalf of the New York-based firm that year to wire fraud charges brought by the Department of Justice, and the Securities and Exchange Commission ban followed in January 2013.

Prosecutors said Tiger Asia was allowed to see confidential information ahead of block trades — big stock sales often made at a discount — that were orchestrated by banks including UBS and Morgan Stanley. As part of the arrangement, Tiger promised to keep the information confidential and not trade on it. Instead, the firm entered into short sales from which it earned millions of dollars, the US authorities said.

“This criminal activity by a hedge fund operator, one of the biggest in the world, is unacceptable,” Paul Fishman, the US attorney in Newark, New Jersey, said at the time of the charges in 2012.

Hwang has credited his faith with helping him get through the difficult times. He told Sandy Cove Ministries last year that, after Tiger Asia’s demise, he had listened to recordings of the Bible for hours, with actor Samuel L Jackson as a narrator.

When Hwang re-emerged with a family office, he named it Archegos, an ancient Greek word meaning a leader. In the Bible, Jesus was described as the Archegos, the “author” of salvation.

Hwang also founded the Grace and Mercy Foundation in 2007, where his wife is a director and Andrew Mills, the co-chief executive of Archegos, was the vice-chair. The foundation’s tax records show it made substantial donations to the Fuller Theological Seminary, an evangelical institution where Hwang is a trustee, and the Museum of the Bible.

“My goal is to nurture capitalists that benefit the world that God loves,” Hwang said in an interview five years ago. “Money is a gift that God has given me to share with others.”

Hwang’s downfall last week came after he was unable to meet margin calls on derivatives trades, known as equity swaps, that he struck with investment banks. These instruments gave him a chance to gain from stock positions without having to own the underlying shares himself.

The result was rich in irony. The banks sold shares they held for the swaps in giant block trades. However, instead of offering to sell millions of dollars of shares to Hwang, the likes of Morgan Stanley last week sold billions of dollars worth of stock because of him.

Hwang did not respond to multiple requests for comment. The fund has said it was “a challenging time for the family office . . . our partners and employees”.

Additional reporting by Tabby Kinder in Hong Kong and Leo Lewis in Tokyo

Comments