A player miskicks the ball – skies it – and its clatter on the metal roof is the loudest sound in the Covid-emptied stand. There’s not much by way of a corresponding stand on the other side of the pitch, mostly just advertising boards and a momentarily malfunctioning scoreboard. Behind them a hillock, behind that a sunset. There’s an ill-timed tackle, a melee of angry players, a red card for the home team. But the visitors, Colchester United, look rudderless – it’s the first game for their interim manager – and 10-man Forest Green Rovers run out 3-0 winners.

If much of this is a typical scene of lower-league football, as played out all over the country every week of the season, in some crucial details it is not. It’s partly the setting that’s different, on a hill outside Stroud in Gloucestershire, in a landscape more redolent of point-to-points than professional football. “Jilly Cooper loves Forest Green Rovers!” says one of the billboards – a tribute from a local author to the local team. “Red sky at night,” says one of the few people permitted to be there, as he contemplates the sunset, “shepherds’ delight.” I’m pretty sure I haven’t heard that line of commentary at a football match before.

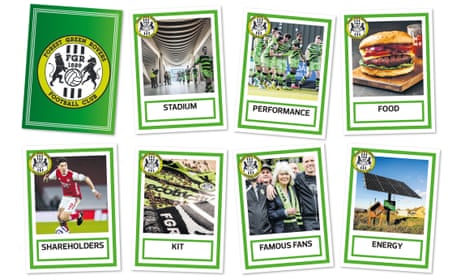

And then there’s the fact that the players’ striking strips (lime green with a black zebra-stripe pattern) are – tonight, for the first time for any team anywhere in the world – made with a composite of waste coffee grounds and recycled plastic. The pitchside adverts don’t only celebrate Cooper’s raunchy, horsey novels but also brands associated with healthy and sustainable living: Quorn, Oatly, Innocent, Elixinol cannabidiol products, Grundon environmentally friendly waste management. One has the skull and crossbones insignia of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society: Defending Ocean Wildlife Worldwide, it says. My stomach is getting to know a shiitake mushroom burger I ate just before kick-off, and finding it less confrontational, digestion-wise, than the traditional meat-and-whatever-else version that is served at football grounds.

For this is Forest Green Rovers, declared by Fifa the “greenest team in the world”, certified by the United Nations as the world’s first carbon-neutral football club, which in the decade since its acquisition by the green energy industrialist Dale Vince has become famous well beyond its size, for its sustainability and, especially, for the all-vegan menus offered to both players and fans. It’s not stopping there: apart from the coffee kits, there’s also a plan for a new all-timber stadium designed by Zaha Hadid Architects, which in February was approved by the English Football League, having won planning permission from Stroud District Council last December.

Nor are Vince’s wider range of eco-initiatives slowing down. He shows me some diamonds on the Zoom screen, made with carbon (incredible as this may seem) taken from the atmosphere, a process that he says reduces the colossal waste that comes with mining the precious stones. He already has Devil’s Kitchen, a vegan food business spun off from the football club, which makes burgers, plant balls and suchlike, now available through Ocado. The main source of his wealth is Ecotricity, a renewable energy supplier that developed from the windmills Vince erected in the 1990s. He created Nemesis, a Lotus Exige chassis modified with electric motors and batteries, which in 2012 broke the UK speed record for electric cars. Last month, he teamed up with the Daily Express, of all newspapers, to promote its Green Britain Needs You campaign.

Vince’s speciality is to bring green practices and ideas to blokey aspects of life not usually associated with such things: football, burgers, cars. Or, three decades ago, energy provision. “You have the most fun and most impact preaching to the unconverted,” he says of his work with the Express. “On the right wing of life the people at the Express have had people saying to them: ‘What are you doing working with that bloke?’ and on the left wing of life I’ve had people saying to me: ‘What are you doing working with that newspaper?’ And we both say the same thing – we can’t live in our bubbles, we’ve got to talk to each other.”

Vince, 59, is the sort of have-a-go entrepreneur who you might have thought was extinct in a time of corporate leviathans. He is restless, rapid-speaking, both engaging and elusive, his manner at once laidback and wired. I’m told by people who’ve dealt with him that he is both shy and direct, that “he doesn’t hang back from expressing opinions”, that he can be assertive, that he “doesn’t suit the more English-y sort of people”. As he describes himself in his recent book, Manifesto: “I look at and do things my own way. It’s got me into plenty of trouble but it’s also a bit of a superpower.”

He might now be described as “Britain’s richest hippy”, living in a castellated former fort on a hill above Stroud, with a large solar array in its untamed garden, but he once had almost nothing. The son of a Great Yarmouth lorry driver, he left school at 15 and spent years as a traveller, living in a lashed-up old ambulance, or a pickup truck, or a bus, driving a 30-year-old fire engine to Spain, riding motorbikes, moving from one site to another – “old airfields, gravel pits, car parks”, as Vince writes in Manifesto. In 1985 he was embroiled in the notorious “Battle of the Beanfield”, an outbreak of what he calls “wanton state-sponsored violence”, an assault by 1,300 police on 600 travellers heading towards Stonehenge.

In 1991 he had “an epiphany”. He’d already made a little money putting up improvised wind-powered phone stations (“windphones”) at the Glastonbury festival, and he’d added a small windmill to his trailer, connected to old train batteries he’d rescued from a scrapyard, capable of 50 watts, enough for two dim lights and water pump. The first big power-generating windmills in Britain were built that year, in Cornwall, and Vince decided to have a go himself. He educated himself on “aerodynamics, mechanics, electronics, statistics… windmill technology, planning and environment assessments, grid compatibility, financial modelling, construction”.

He made his own 30-metre mast for testing wind speed, won the co-operation of the owner of the hill, and spent his last “few hundred quid” on some respectable clothes and a flight to Germany to meet the manufacturers of the then-unconventional variable-speed windmill that he wanted. He gained planning permission. Representing himself in court, he defeated a legal challenge from the National Trust. He negotiated a connection to the local grid, raised £350,000 in finance and, five years after his epiphany, got the windmill up and running.

This was the beginning of Ecotricity, a company that in 2019 had a turnover of £201m. Later, Vince turned to electric transport: the Nemesis project never turned into a mass-produced car, but it did lead to the Electric Highway, a national network of charging points. Vince’s company had to fight off an attempt by Elon Musk and Tesla to shove them aside, but it now has 300 stations across the country.

Forest Green Rovers now looks like a perfect extension to the Ecotricity brand – it even has “green” in its name – but Vince insists that its transformation into a “global force” was “serendipity”. “I just bumped into it along the way. It was a rescue mission, only that.” The club was “leaking money everywhere… it was about to fold. I thought that was wrong. It was a big part of this community, 120 years old, lovely people. They invited me to a game. It was fabulous, like a small theatre, intense and personal.”

He stepped in and bought it. “On day two I bumped into the fact that we were serving red meat to our players and I thought: ‘Oh my God, we’re part of the meat trade, I can’t be that,’ so we had to make that change.” They realised, he says, “that we might not be speaking to the most receptive audience, but that only added to the appeal of doing it. The one thing everyone wants to know is how can you have a vegan menu without having a riot from your fans.” The answer, he says, was to show that “food without animals in is great food”. The club’s players “were the easiest audience of all. We simply said to them that red meat will impair your performance.” It’s now widely recognised among elite athletes, says Vince, that vegan diets improve performance and reduce injury. The Manchester City striker Sergio Agüero, for example, goes on a vegan diet during the football season.

So they sell the fans pies, sausage rolls and burgers, chips and gravy, all plant-based, as well as options that are not imitating meat. Away supporters, the club chef Jade Crawford tells me, mockingly turn up in butchers’ aprons. They chant “Where’s your burger van?” But, she says, the products she offers “sell out, so they must like them”. Some home fans “said at first they were a bit annoyed about it. They said they might stop coming, but they tried the food and said it was really good.”

The diet has grabbed most of the headlines, but there are other aspects to Forest Green’s greenness: power from solar panels and from Ecotricity’s green energy, a pitch free of chemical fertilisers or pesticides, charging points for electric cars, the capturing of rainwater from the roof to irrigate the pitch, an electric van for the kit man, and soon, it is hoped, an electric team bus. There’s a well-publicised “mow-bot”, a GPS-directed solar-powered lawnmower.

Forest Green Rovers’ performances on the pitch have improved since Vince’s takeover. Once teetering on the edge of relegation from the Conference, the fifth tier of English football, they were later promoted to League Two, which in the logic-free system of numbering these things is the fourth tier. They currently have good prospects of promotion to League One and hopes of eventually getting to the level above that, the Championship.

The combination of veganism, sustainability and some sporting success has brought them global attention. They have 100 fan clubs in over 20 countries, such as the Forest Green Rovers Chicagoland Supporters group, foundedin 2016 by people who “shared a passion for the environment and soccer”. The Arsenal full-back Héctor Bellerín, attracted by the club’s ethos, has become a shareholder. “Engaging fans through their favourite sport and getting them to be fans of the environment” is what Vince calls it. The United Nations invited the club to be founding members of its Sports for Climate Action programme, which, he says, “is pretty much based on what Forest Green have done”. Bigger names have followed where Forest Green Rovers have led. The mighty Real Madrid recently announced a partnership with the British plant-based producer Meatless Farm to encourage sustainable eating (still a lesser level of commitment to the environment than that of the Stroud side).

The future stadium, which will use contemporary timber engineering techniques to achieve its all-wooden structure, is intended as a vehicle to get the club to the next level, while also promoting its principles. It will have a capacity of 5,000, with the ability to go up to 10,000 or 12,000 without too much difficulty, which would be big enough for a Championship side. “We might shoot for 15,” says the ever-ambitious Vince. Because timber is renewable, and absorbs carbon during its growth, it greatly reduces the carbon and energy costs that go into construction, which might be three times those expended on such things as light, heat and power used over the lifetime of a stadium.

The stadium’s completion is still some years off, not least because it is to be part of a grander plan: a “Green Technology Cluster”, a “truly sustainable” business park that aims to create up to 4,000 jobs. Some 20% of the 50 hectare site is to be wetlands, alongside a restored stretch of a historic canal. The location is currently green fields, next to Junction 13 of the M5. This doesn’t sound environmental – neither building on fields nor relying on road transport – but “farmed fields are wildlife deserts”, Vince says, and his proposals will provide more biodiversity than the land they replace. There are not many options for getting fans to his stadium by public transport, but he promises electric buses and cross-country walking and cycling routes.

The seductive images of the project show an elegant curving form rising out of a lush green landscape, its undulations echoing the soft hills behind. In some ways it is what you would expect from Zaha Hadid Architects – striking forms are their thing, and their work on the London 2012 Aquatics Centre and Al Wakrah Stadium for the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, as well as their now-abandoned designs for the Tokyo Olympic Stadium, have made sports buildings one of their specialities. On the other hand, the Forest Green Rovers project is small by the current standards of this global practice, and their designs – which are almost always in concrete and steel – have not hitherto been especially noted for their sustainability. The mighty roof of the Aquatics Centre, for example, used prodigious quantities of steel.

Alex de Rijke, an architect who has pioneered modern timber construction, including a proposed wooden handball arena for the London Olympics, is sceptical that ZHA are the best people for the job, given their previous lack of interest in timber structures. It’s “excellent that Forest Green are building a timber stadium”, he says, but wonders whether this design grows out of the structural characteristics of wood or steel. He suggests that the practice isn’t usually driven by optimised use of sustainable materials, but by what he calls “the dogged mission to invent novel forms” – the desire, to put it another way, to look striking.

Jim Heverin, the director at ZHA in charge of the project, acknowledges that this is partly new territory for them, which was part of the attraction of the job: they want “to grow out of the shadow of what people think we are, and carbon is the challenge of our generation”. He says that the design does pay attention to issues such as waste – the curving silhouettes are made out of assemblies of straight elements, for example – and as it develops they will also consider such matters as the distance the materials have to travel from their place of origin.

He’s also clear that looking striking – the power of the image – is important to the practice, and that the project “will cost more than normal because it’s not conventional – you can’t just buy it out of factories”. This reflects an aspect of the Vince philosophy, which is that “whether it’s burgers, cars or football we can still have fun doing it differently”. The idea of Nemesis, he once said, was to “smash the boring, Noddy stereotype of the green car”. His current plan for mining the sky for diamonds is “bling without the sting”.

Which brings up a core question behind the whole Vince enterprise: what’s the substance, what’s the spectacle, what is what he calls “storytelling”? It’s hard to think, for example, that a solar-powered lawnmower will make a huge impact on the club’s carbon footprint; its role is more to be an eye-catching messenger of its values. But it’s hard to argue with the seriousness of his overall achievement. The point of his combined ventures is that they are all of the above: they combine the humdrum business of large-scale energy provision with the coffee kits and the shiitake burgers that get environmental messages to hard-to-reach audiences.

His hometown of Stroud, birthplace of Extinction Rebellion, is the sort of place that would give short shrift to greenwash. Although his building proposals have attracted objections, there doesn’t seem to be much by way of significant challenges to his overall green credentials. The worst thing I hear about him is that his presence is a bit too dominating, looking down on the town from his castle, his burger-windmill-diamond factory and frequent Ecotricity banners being hard to miss. “It’s a bit medieval,” I’m told.

Molly Scott Cato, a Stroud resident who until Brexit was a Green party MEP for South West England, has had some political confrontations with the Labour-supporting Vince, who wanted the Greens to step aside at the last general election. But she said that “it’s brilliant for the town having a renewable energy firm” and that the “football club is really important in reaching out to people that are hardest to get to”. He may not, with his flurries of initiatives, always get everything right, but collectively they’re a force for good. If Forest Green Rovers raise the question: how much impact can a League Two football club have, the answer is quite a lot.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion