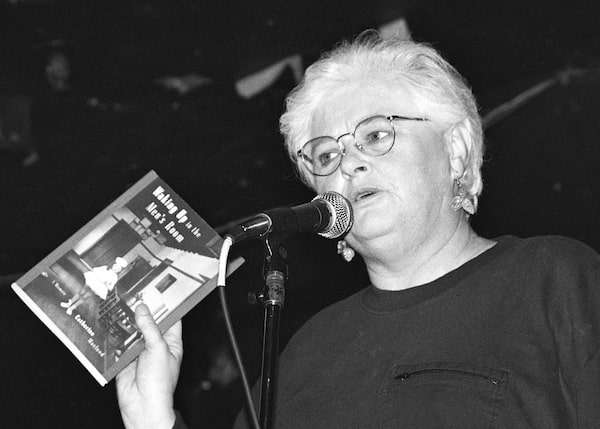

Catherine Macleod.Vincenzo Pietropaolo

Hours before she died at her home in Goderich, Ont., on March 8, Catherine Macleod, a writer, poet and social activist, sent a text message to her friends to mark International Women’s Day. It was a poster featuring the legendary Mexican feminist and artist Frida Kahlo.

The poignant goodbye came from a conscious romantic who devoted her adult life to women’s rights and the arts. In her memoir, she wrote, “for women, the personal and the political were the same.”

During the many years she spent working in the labour movement, Ms. Macleod also helped forge a new era of collaboration between unions, artists and community groups.

The eldest of three children, Ms. Macleod was born on June 10, 1948, in a working-class family in Glasgow, Scotland. Her mother, Catherine (née Corr), was a devout Catholic, her father, Robert, was Protestant. The children were raised Catholic. The family was dirt poor and lived in a two-room tenement house in the centre of town. Her father worked six-and-a-half days a week as a millwright in the shipyards. Her mother did all the housework, occasionally taking retail or factory jobs as well to make ends meet.

Ms. Macleod was a founding member of the Canadian Women’s Educational Press Collective, later the influential Women’s Press.Vincenzo Pietropaolo

Ms. Macleod’s early childhood years were spent in the aftermath of war-ravaged Glasgow, and would give rise to a poem: “there was a hole in each corner / and bed in the Glasgow tenement wall / for me, my mother, and my dad / who snored in his watch / and socks.”

With shipyard layoffs looming, the family immigrated to Canada in 1957. Initially they were met with hardship and lived in a trailer without running water outside Hamilton. But by 1963, Mr. Macleod had obtained a coveted job in Kincardine, where Ontario Hydro was building the Bruce Nuclear Generating Station on the Lake Huron shore. The family finally found a permanent home.

Growing up in the quiet rural town, Ms. Macleod was torn between her conservative Catholic upbringing and her desire to learn about the world beyond. Her sense of class was dominant in her life, and she always carried the working class “like a locket in my fist.” But she was determined to break the cycle of marriage-children-factory work expected of young women of her background. She had a boyfriend, Martin Quinn, but a relationship was not enough to make her embrace small-town life.

By 1968, she had moved to Toronto, attracted by the counterculture and the arts scene. She dreamed of becoming an artist. She was disappointed by gender discrimination in the male-dominated office where she worked and even more disillusioned by the patronizing attitude of the artists and social activists she met and admired while living in a hippie commune.

In her memoir, she recalled how she fell in love (unrequited) with one hippie, who had “an LSD-induced angelic face and played guitar in the flowering sidewalks of Yorkville Avenue,” and ended up supporting him on wages from her office job. Another boyfriend who was in law school counselled her not to attend university because a “bourgeois education would spoil a working-class girl like her.” So, she enrolled at the University of Toronto in 1971, taking the first Women’s Studies course on offer and earning a BA.

Ms. Macleod's intensely personal 1998 memoir Waking Up in the Men’s Room is an astute feminist analysis of political culture and gender politics.Vincenzo Pietropaolo

University changed her life. It became the doorway to Marxist analysis and feminism, the political consciousness that would become the guiding force in her life journey. Ms. Macleod felt empowered, and her activism flourished.

She was a founding member of the Canadian Women’s Educational Press Collective, later the influential Women’s Press. Their first book was Women Unite! An Anthology of the Canadian Women’s Movement (1972). She gave birth to her only child, Grayson Taylor, and when her best friend, Pat Schulz, died, Ms. Macleod became the guardian of Pat’s teenage daughter, Katheryne.

Filmmaker Laura Sky credits Ms. Macleod with bringing her into the women’s movement. “Catherine brought me into my first consciousness-raising group – which felt like new and provocative territory – feminist politics intertwined with socialist analysis. It was a life-changing experience.”

In 1986, Ms. Macleod was instrumental in creating the Mayworks Festival of Arts and Working People in Toronto, showcasing artists working for social change. According to visual artist Carole Condé, “Catherine was the spark and energy that brought together people from the arts and the labour movement in the 1980s and 90s, and was the crucial link between all of us who were involved. It not only built Mayworks, but led to hundreds of labour arts projects.”

Throughout this hectic period of organizing activity, she found time to write the first of three books of poetry, Lessons Never Learned, and the first of three plays, Glow Boys.

After a brief stint at the Ontario Public Service Employees’ Union, in 1987 Ms. Macleod was recruited by the Canadian Auto Workers Union (forerunner of Unifor), then the largest private sector union in the country. On her first day in the job she flew to Newfoundland and Labrador to help in a controversial campaign to organize the fishery workers. It was a hectic pace that never slowed down and took Ms. Macleod as far as Mozambique and Nicaragua to work on the union’s Social Justice Fund projects.

In the 1990s she was communications director for the Ontario Federation of Labour, and later also a communications rep for the Canadian Union of Public Employees. These were years of intense labour unrest in the aftermath of the NAFTA agreement: plant closings, along with major cuts in social services, health care and education.

In 1986, Ms. Macleod was instrumental in creating the Mayworks Festival of Arts and Working People in Toronto, showcasing artists working for social change.Vincenzo Pietropaolo

Ms. Macleod found herself in the eye of a political storm as she and her colleagues at the Ontario Federation of Labour organized walkouts and massive demonstrations in 11 cities across Ontario. The militant action united teachers and health-care workers and government and industrial workers into a coalition that included community groups and arts organizations. The protests were entirely peaceful and climaxed in the largest protest in Toronto’s history on Oct. 26, 1996, when some 250,000 people marched from Exhibition Place to Queen’s Park. It was a historic moment. Virtually the entire city was closed, including the subway system.

Ms. Macleod had her share of disappointments, but with her effusive and warm personality she always focused on the bright side. When writer Jamie Swift once expressed to Ms. Macleod his own disappointment that a modestly attended protest received scant media attention, she quickly replied, “But we saw each other.” Mr. Swift recalled, “This was one of my favourite things about Catherine. She had these profound insights that reflected so much of her natural wisdom.”

Her legacy includes raising consciousness, especially of young women.

Her intensely personal 1998 memoir Waking Up in the Men’s Room is an astute feminist analysis of political culture and gender politics. The Toronto Star’s Thomas Walkom called it an “extraordinary story of an ordinary person.”

One night her high-school sweetheart came calling. She had not seen horticulturalist Martin Quinn in 30 years. They were both single parents but their youthful love from the 1960s was rekindled. In 1992, Ms. Macleod married her Mr. Quinn, finally deciding to “listen to my mother.” The couple settled in Kincardine, later moving to Goderich, Ont. Mr. Quinn became her devoted caregiver, at her side through to her final moments of life.

Ms. Macleod, who died of progressive supranuclear palsy at age 72, leaves her husband; son, Grayson Taylor; daughter, Katheryne Schulz; stepson, Joe Quinn; sister, Janis Shewfelt; brother, Robert; two grandchildren and extended family.