Whether you’re me or the Duchess of Sussex, to be Black is to always be negotiating around the bias of others. Racism is omnipresent. White supremacy is the west’s original sin.

But what about when charges of racism seem to be made up? Assessing people from the past by the standards of today, as lots of young people seem to do, no one is perfect. But, antagonistic to human frailty, for want of sufficient purity, many are prone to dismiss people who offer much that recommends them.

Despite Dr Martin Luther King Jr praising her for affording Black women choice and Black couples self determination through family planning, Margaret Sanger is said to have advocated Black genocide. Even “the Emancipator”, Abraham Lincoln, is called racist. It’s mostly for things he said to avoid division and prevent war. It doesn’t seem to help that he was esteemed by Frederick Douglass as a personal friend, as well as a friend to the “colored race”. Lincoln helped pass the 13th amendment and envisioned the 14th and 15th. But his dying for advancing all three seemingly means nothing?

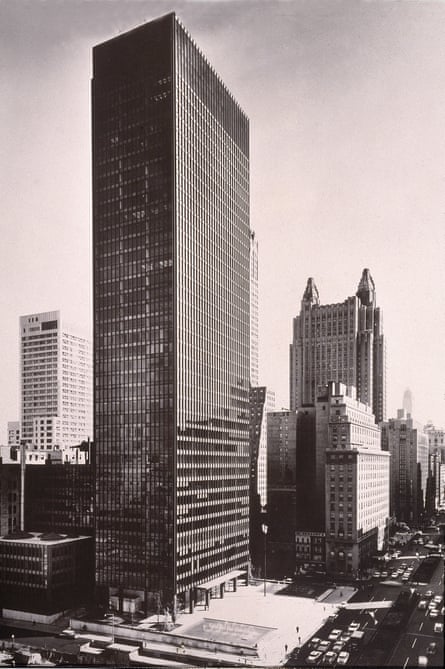

The latest example of calling out someone dead as racist is going on at the Museum of Modern Art. Opened 27 February and running through to the end of May, a new exhibition, Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, challenges and seeks to dismiss the legacy of Philip Johnson, the modernist master who did so much to start and cultivate MoMA. Presented in a gallery dedicated to Johnson’s memory, the participants’ introductory manifesto obliterates an inscription in his honor.

It is a disquietingly existential exhibition, big on abstract ideas but with little by way of actual buildings to show. The organizers contend: “We take up the question of what architecture can be – not a tool for imperialism and subjugation, not a means for aggrandizing the self, but a vehicle for liberation and joy.”

Johnson’s “white supremacist views and activities”, they say, “make him an inappropriate namesake within any education or cultural institution that purports to serve a wide public”.

But when the goal is inclusion, is a tit-for-tat banishment necessary or even useful? Already successful in removing Johnson’s name from a building he designed at Harvard, some seek to “cancel” him at MoMA too.

As an American correspondent covering the rise of Nazi Germany, Johnson was all his harshest detractors say. He envisioned a fascist revolution with elite leaders. Hegemony, patriarchy and privilege convinced Johnson the brute force of the state, allied with technological advance and modern aesthetics, could end suffering for the poor, increase wealth and defeat communism.

Once war loomed, he turned on a dime. Enlisting in the US army, he became a democratic patriot. Even so, perhaps his greatest friend, the gay, Jewish artistic impresario, connoisseur and philanthropist Lincoln Kirstein, who established and cultivated the New York City Ballet in much the same way Johnson promoted MoMA, would not talk to him for two years.

At issue then, as now, was Johnson’s past Nazi infatuation, as well as his racism. But is racism no worse than most people’s irredeemable?

Historian Robert AM Stern is Jewish. He counts Johnson as a critical mentor. TV commentator Barbara Walters developed a friendship with Johnson after she reprimand him for not being out and proudly gay.

According to the Black architect Roberta Washington, at work on a history of African American designers in New York state, “Johnson employed at least two Black men whom I’ve interviewed for my book”.

Professor Steven Semes, of Notre Dame, recalls others from when he worked for Johnson in the 1980s. The first was Percy Griffin, a Mississippi native whose family were sharecroppers. Griffin has said both he and Julius Twyne got along well with their former boss. Far from having faced discrimination, Griffin expressed gratitude for an exception which allowed him to work part-time and without a license.

“He paid me full pay,” Griffin told the Architecture School Review, “the same pay he gave to the architects that had already graduated, for five years, and I took off any day that my class was going on, and he never took off a dime.

He kept paying me the same he paid everyone else … for five long years. And he also gave me personal crits on my school projects … I got the chance to meet Louis Kahn, Salvador Dali, Andy Warhol and others and go to parties with them, because they all knew Philip Johnson and he would invite everyone to the party. I wouldn’t trade that for any school in the entire world: Going to school up at City College, and being in the office of Philip Johnson.”

I was a friend of Johnson’s older sister, Jeanette Dempsey, in his hometown, Cleveland. I met Johnson after moving to New York in 1985. He was fascinating. He told me how, more than a century before, the Black architect Julian Abele worked hand-in-hand with white practitioner Horace Trumbauer as his head designer. Johnson called the house Abele designed for the industrialist James Duke, now the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, “exceptional”.

In the grill at the Four Seasons he remembered how, back from Germany in 1934, he made a fateful jaunt to Harlem’s Club Hot-Cha. On seeing the elegant African American singer Jimmie Daniels, Johnson said, he determined to make the beautiful youth his lover.

Johnson could be exceedingly charming. But had he really repented? His Jewish friends and Black employees thought so. So do I.

A fellow gay Ohioan, at least I’m invested in hoping Philip Johnson’s youthful outrages are forgivable, that his recompense and reconciliation, and mine, are a possibility. None of us only amounts to our worst mistake. Today, we all need what Philip Johnson died imagining he’d found: the opportunity to evolve – a chance to become better people.