Fox News Flash top headlines for March 16

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

I never got to meet legendary CBS and NBC correspondent Roger Mudd.

That’s a regret of mine.

Mudd died last week at age 93.

I always wanted to meet Mudd because he covered Congress for CBS. I read Mudd’s 2008 book "The Place to Be." What intrigued me about the book were his tales about covering Congress for so many years.

I generally don’t seek out celebrities or public figures. I report on a lot of them. It’s part of the job. So I never reached out to Mudd.

ROGER MUDD, LONGTIME NETWORK TV NEWSMAN, DIES AT 93

But after reporting on Congress for decades, I could understand every syllable of Mudd’s book.

Growing up, I recall watching Mudd substitute for Walter Cronkite on the CBS Evening News and report from Capitol Hill – long before I ever had any notion to visit Washington let alone report on Congress. Mudd lost out to Dan Rather to succeed Cronkite as anchor of the CBS Evening News. Mudd then bolted for NBC.

As a young adult, I sometimes saw Mudd appear on the old "MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour" on PBS and pieces on the History Channel.

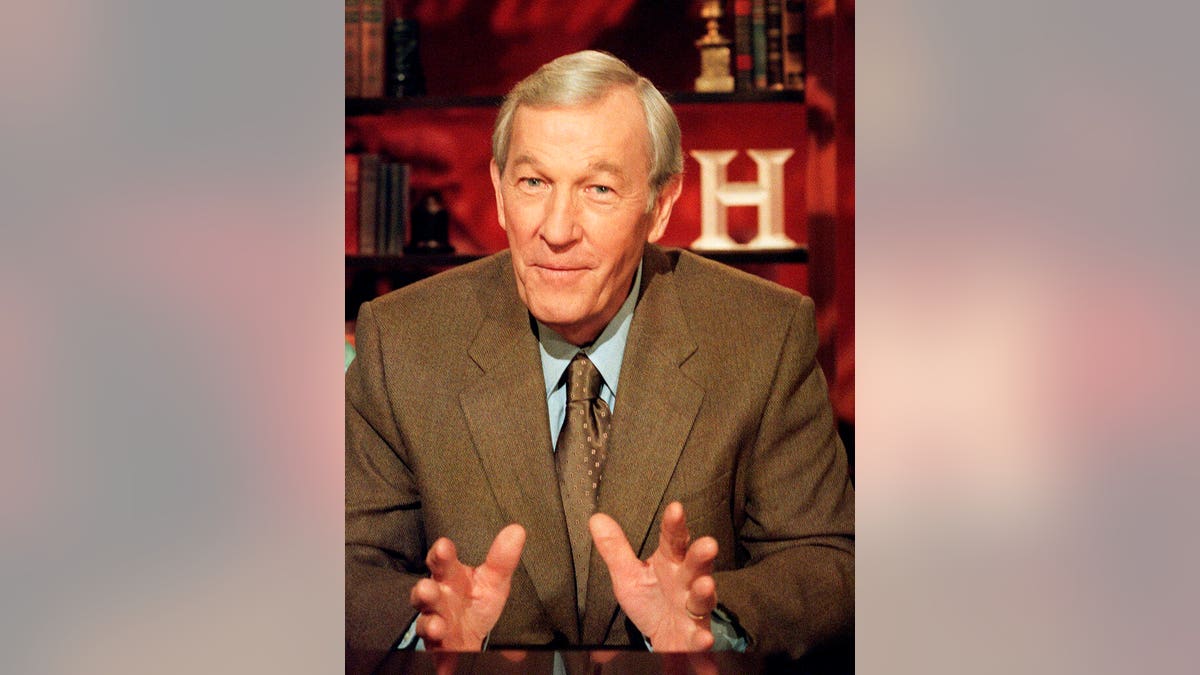

In this Aug. 6, 2001, file photo, veteran journalist Roger Mudd tapes a segment for the History Channel at CBS studios in New York. Mudd, the longtime political correspondent and anchor for NBC and CBS who once stumped Sen. Edward Kennedy by simply asking why he wanted to be president, died Tuesday, March 9, 2021. He was 93. (AP Photo/Marty Lederhandler, File)

And then I read Mudd’s book.

The title "The Place to Be" refers to CBS’s status as "The Tiffany Network" when Mudd and others were there. But as a reporter, I’ve always thought of Capitol Hill as "The Place to Be." Anyone who’s ever covered Washington will tell you reporting on Congress is the best beat in town – with the caveat that the past several months may be an exception.

However, what struck me about Mudd’s tome is how little about reporting on Congress has changed – whether it be his time here in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s or 1980s – compared to today.

Sure, the players and some of the issues are different. But the principles of reporting Congress remain the same. Walking around the halls, chatting up members in the hallways. Searching for a tidbit of information. Doing live standups out by what is now called the "Senate Swamp" not far from the Senate steps, the Capitol Dome looming in the background. Even dealing with Congressional staff and the U.S. Capitol Police.

In many respects, that’s refreshing. Perhaps because Congress, for better or worse, still functions the same way it did decades ago. The sponsors of legislation still have to massage the issue and twist arms to get the measure to pass. You still need a majority to pass a bill. There are still committees. The leadership structure in the House and Senate are similar.

And information is always the currency on Capitol Hill. It was then. It remains so today.

I heard someone declare a few years ago that if Ty Cobb stepped onto a baseball field now, he’d feel right at home. Still four balls for a walk. Three strikes and you’re out. Ning innings. The fundamentals haven’t changed. However, baseball purists may argue new rules like a "clock" between half-innings, prohibitions in the minor leagues against the shift and a new mandate that pitchers face at least three batters would have mystified the Georgia Peach.

Of course, when he played, Cobb was known for sharpening his cleats and spiking fielders when he slid into second or third base.

For the record, cleats are still sharp on Capitol Hill as "baserunners" often try to spike their political adversaries.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

And, the tenets of Congressional journalism are immutable.

Mudd wrote about his efforts to interview a Congressman who made controversial comments. It’s not all that different from what the Capitol Hill press corps goes through today to chase down an interview with someone in the corridor, or better yet, on camera, if they’ve uttered something controversial.

Mudd recounts the "Where were you when…" moments of covering Capitol Hill. Mudd described how a CBS colleague was watching the Senate from the press gallery when the late Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-Mass., was presiding on November 22, 1963. A Senate staffer rushed up the Kennedy: "Your bother’s been shot."

You can imagine the questions I get, asking about where I was at the Capitol when rioters breached the building on Jan. 6.

Mudd writes about the late Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, D-Mont., practically shouting as he delivered President John F. Kennedy’s eulogy in the Capitol Rotunda as he lay in state. Then the throng of public mourners, coursing through the Capitol’s bronze doors to pay their respects.

Numerous figures have laid either in state or in honor in the Capitol Rotunda since Kennedy’s ceremony. That doesn’t change. Even two during the pandemic. The late Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., laid in state last summer. Late U.S. Capitol Police Officer Brian Sicknick laid in honor after the January 6 melee. In recent years, the Capitol press corps has also covered ceremonies for the late President George. H.W. Bush and the late Rev. Billy Graham.

Editorially, Mudd was best known for a 1979 interview where he stumped Edward Kennedy with a question about why he wanted to be President. Political analysts believe that interview ended any presidential prospects for Kennedy.

Even today, the Capitol Hill press corps finds itself pursuing those who want to be President.

In recent years, reporters have dashed after Sens. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and Marco Rubio, R-Fla. It wasn’t that long ago that there were similar drills surrounding then Sen. Barack Obama, D-IIl., and then Sen. Joe Biden, D-Del.

Mudd tells a story of balking at an assignment from his bureau chief "to cover the Romney speech tonight at the Governors’ Conference."

That’s the late Gov. George Romney, R-Mich., father of current Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah.

Things never change.

There’s been all sorts of conversation of late about altering Senator procedures to eliminate the legislative filibuster in the Senate. Mudd spends a good portion of his book describing how there were 11 attempts to overcome the filibuster which stymied civil rights legislation. Mudd described tactics of "small-state senators" who sometimes would block legislation because of their outsized influence in the Senate, thanks to the filibuster.

A similar statement could be written today about a host of legislative issues, gummed up by the filibuster.

Mudd recounted stories of sitting in the Senate press gallery, overlooking the chamber, watching senators and scribbling down notes. Reporters follow the same rituals today.

And this sentence rings as true in 2021 as it did in the mid-1960s:

"Our cameras were not allowed in the Senate chamber," wrote Mudd.

Private, newsgathering cameras, be they from Fox, CNN, ABC or anyplace else, still aren’t permitted in the House and Senate chambers. The video you see comes from cameras controlled by the institutions.

To make up for this visual deficit, CBS would hire a sketch artist who would take some mental notes and then illustrate the Senate’s doings on canvas. A photographer would then then film the drawing. Any film shot anywhere on Capitol Hill had to be processed. A motorcycle courier would sprint up to Capitol Hill, dodge traffic en route to Georgetown to have the film developed then race to the CBS bureau to enroll it into a TV piece.

We don’t do that any more.

But all it takes is one tweet to go viral and your entire story pivots. At the rate news churns in Congress, you may as well be careening your way down Capitol Hill on the back of a motorcycle, trying to keep up.

Congress is not an easy place to understand. There are so many unwritten rules. Written rules. Customs. Traditions. Pageantry. Formalities. It’s a parliamentary labyrinth. And, it takes some dedication to make sense of it all.

"I found myself peeling back the layers of the Senate’s skin and discovering that the legislative process was really not so much a process as it was a changing mixture of tradition, arcane rules, bruised egos, hardened public opinion, soaring vanities, senatorial ignorance, genuine patriotism, posturing, knee-jerk reactions, low motives and high principles," wrote Mudd.

Mudd describes how one "leading and powerful southern Senator" asked the network why the Senate shouldn’t prevent him from doing his reports at all. After all, the reports were "‘being televised on Senate property.’"

A complaint that direct doesn’t come up today – although some Republicans routinely question whether platforms such as Facebook and Twitter shouldn’t be regulated because of a perceived liberal bias. And squabbles with the Radio/TV Gallery, Sergeants at Arms and even members themselves still persist over the placement of television cameras and who can shoot video where. But today, with an iPhone.

Mudd notes that he used to get complaints from the Capitol Police about where he was allowed to be by the Senate steps for his standups. Hassles like that still exist.

Today’s Congress is populated by Reps. Matt Gaetz, R-Fla., and Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif.

The Congress Mudd covered featured characters like House Speaker Sam Rayburn, D-Texas, Sen. Richard Russell, D-Ga., former Senate Majority Leader Howard Baker, R-Tenn., and Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen, R-Ill.

Different dramatis personae. But in many respects, Congress is the same. Covering it is kind of the same, sans the sketch artists and motorcycle couriers.

And I regret I never got to meet Roger Mudd to talk about it.