Thousands of young actors, singers, dancers, and live performance artists flock to New York City every year, fueled by the dream of a starring role on Broadway, the world’s biggest stage. And they hustle for it – working odd jobs to make ends meet, sharing tiny apartments, huddling in long lines to audition for just a handful of highly coveted roles.

But the brilliant lights of Broadway have been dark for nearly a year. And its 41 theaters, including iconic century-old ones like the Belasco, Lyceum and New Amsterdam, will likely remain closed for many months, despite ongoing discussions about potential safety measures, like a cap on audience sizes or requiring attendees to provide proof of a negative Covid-19 test.

The situation is dire for many of the 97,000 people who rely on Broadway for their livelihoods – and for New York City, which benefits from the almost $15 billion generated by the industry each year, according to The Broadway League, a trade association representing producers and theater owners.

Beyond the economic impact, the price of countless crushed dreams is perhaps even greater, according to longtime Broadway performer Reed Kelly, whose stage credits include “Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark,” “The Addams Family,” and “Wicked.”

“I’ve lost three people this year to suicide,” Kelly says. “And that’s on top of the people I know that have actually died from Covid. It’s not just a job for us. This is our lives.”

Gabrielle McClinton, who was last seen on Broadway in the role of Annie in “Chicago the Musical,” echoes the heartbreak and hardship endured by many in New York’s tightknit theater community.

“So many people have lost their jobs, and not just the actors, dancers, and singers (but also) the musicians, ushers and crew people. I know all my friends have been struggling, but they’ve been making it work by creating their own projects and kind of pivoting in different directions – moving more into the TV and film realms,” McClinton says.

Reed’s and McClinton’s dedication to their craft has taken them to the other side of the world – literally. Nearly ten thousand miles from Broadway, in Sydney, Australia, live theater is thriving. The city is one of the few places in the world where performances are open to the public.

‘Making it work’

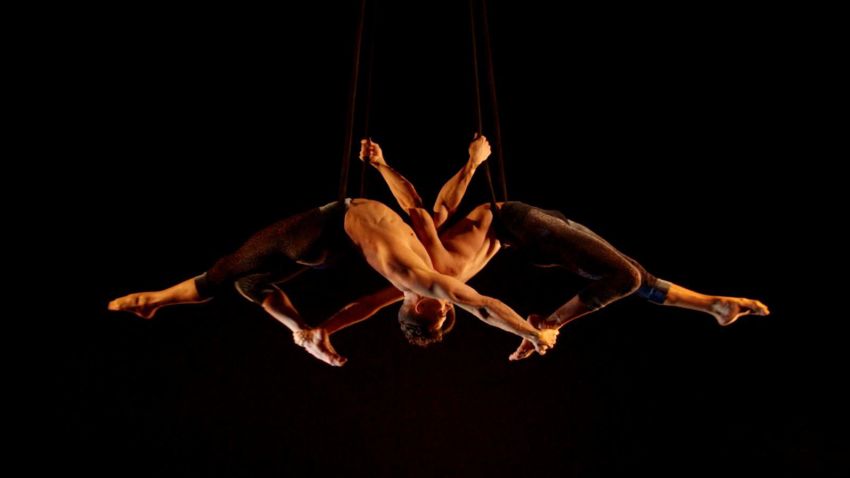

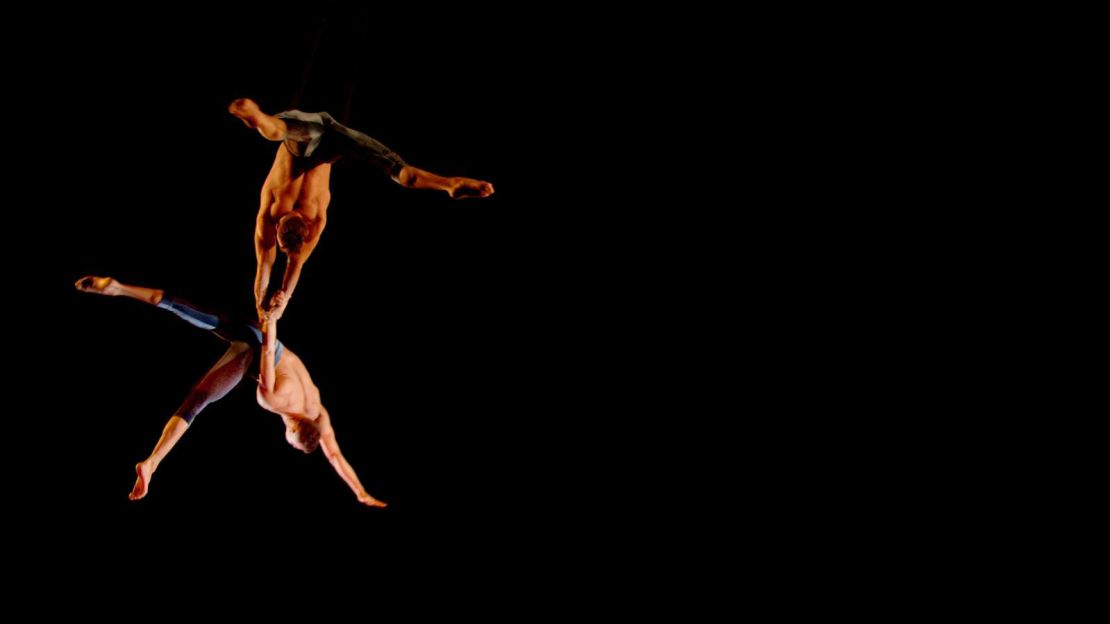

In December, Kelly and Australian acrobat Jack Dawson, who form the aerial straps duo Two Fathoms, debuted “Kismet,” a four-minute act performed in front of a live audience at the Sydney Trapeze School and then released as an online film.

“Right now, this is really the only place that both of us can be – and do what we do,” Kelly says from the school, where he also practices.

What they do takes hours of daily practice and, for Kelly in particular, deep personal sacrifice. He and his husband Balmeet, a doctor in Los Angeles, have been apart for almost a year. But if Kelly leaves Australia, he won’t be allowed to return, given that the country has banned entry to all non-residents since March of last year.

“I’m away from my family. I’m not at home. I don’t get to see my husband. We FaceTime everyday. But it’s been such a challenge.”

McClinton just returned to the US after spending several months in Australia playing a leading role in the musical “Pippin,” which enjoyed a two-month run at Sydney’s Lyric Theatre.

She says the success of live performances in Australia “absolutely” gives her hope about Broadway.

“It definitely had its challenges, but we got through the season. People came to the show wearing their masks and we would get Covid-19 tested every week. When we (weren’t) on stage, we were in our masks and everybody obeyed all the rules and we did our due diligence. And when we were outside the theater we made sure we weren’t putting other people at risk,” she says.

“(In Australia) people are making it work. I know it can work, because we did it. I think if everybody complies, we can make it happen (on Broadway).”

A model for Broadway

Australian playwright Tom Wright says Sydney should offer a model for how to reopen Broadway and the world’s other theater districts. Wright serves as Artistic Associate for the renowned Belvoir St Theatre, which in September became one of the first theaters in Australia to reopen after authorities shuttered venues around the country.

Parts of Australia endured some of the world’s harshest Covid-19 lockdowns at the height of the pandemic last year. But the tough measures – including the imposition of curfews and strict curbs on social gatherings – appear to have paid off, with local cases virtually eliminated.

“The reason why Sydney has been able to reopen is because people at local, state and federal levels took seriously the safety of the most vulnerable people in society. And we’re a reflection of that,” Wright says, adding: “You need political and social leadership to provide a safe set of circumstances for theater to reopen.”

Adhering to local government guidelines, the Belvoir imposes a 75% audience cap and requires visitors to wear masks and register via a QR code at the venue’s foyer.

Sydney’s revival of live theater in the midst of a global pandemic gives hope to performers around the world – especially back in New York, where many of Kelly’s friends are happy – albeit a bit envious, he admits – that he’s working.

“Shows are opening, people are getting the chance to perform, and my greatest wish is to just encourage everyone. Look, I’m an American. I’m over here (in Australia) and they’re nailing it. So, try and get on board, even if it’s not the most comfortable thing. In the long run, it’s the best thing.”