Yves here. Finally, the officialdom is taking interest in excessive influence that Google and Facebook wield in advertising and as media players, even if the original impetus was RussiaRussia. But the whinging generally hasn’t produced much in the way of remedies. Here’s an exception.

By Lynn Parramore, Senior Research Analyst at the Institute for New Economic Thinking. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

Most people know that Google dominates the online search market, but did you know that the company has become the biggest player in the digital ad market? That’s a problem not only for consumers, but potentially for society as a whole, argues former digital advertising executive Dina Srinivasan.

Last year, Srinivasan gained attention for her paper “The Antitrust Case Against Facebook,” which explained how the tech giant’s market dominance can harm the public, even though the product is ostensibly free. Now she focuses on Google and the enormous advertising empire that has grown into the company’s biggest money-maker. In her new paper, “Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets,” Srinivasan analyses the digital ad market and argues that Google’s monopolization and the giant regulatory gaps on matters like transparency and conflicts of interest have created an anti-competitive environment that can be harmful to newspapers, consumers, and, ultimately, democracy itself. She proposes that fairness can be restored by using principles applied to financial market regulation.

Lynn Parramore: After years of inaction, we’re seeing lots of headlines on antitrust actions against Big Tech. The Federal Trade Commission and the attorneys general of 48 states and territories have filed antitrust cases against Facebook, charging that it is able to abuse users’ data and violate their privacy. There are also several parallel suits against Google’s search dominance and chokehold on the advertising market. A good deal of the impetus to these suits comes from work that a number of researchers, including you, have done. How has our knowledge about both antitrust generally and Google and Facebook in particular changed over the last few years?

Dina Srinivasan: I think we have caught up with the fact that there is no such thing as a free lunch. Free does not necessarily mean good for the consumer. Free also doesn’t mean that there aren’t any antitrust problems in the market. For a long time, we thought we could simply ignore the social network and search markets because they were free to the consumer. Now we have historic antitrust cases brought in both markets. 48 attorneys general have initiated antitrust action against Facebook’s zero-cost social network to defend a people’s privacy. That’s fantastic.

In online advertising markets, we’re catching up with the fact that these markets operate and look like other electronically traded markets. This new perspective helps one understand when and why certain trading conduct is good or bad.

LP: Let’s talk about how the online advertising market works for the ordinary person. Say I’m waiting for the train and pull out my phone. I read a newspaper article about a recipe and then click on a cookbook ad. What’s been happening with ads while I’ve been doing my thing?

DS: In the milliseconds that it takes for that newspaper article to load, there’s a complex trade that concludes in the background. As soon as you visit that newspaper website, the newspaper’s sell-side middleman—called an ad server in online advertising markets—routes the empty ad space on that page to multiple ad exchanges.

Each exchange races to sell that ad space to the highest bidder in its little auction, hosting an auction and determining the highest bidder. An important point here is that the bidders here are not advertisers like Procter & Gamble or your local dry cleaner but these advertisers’ buy-side middlemen. You see, advertisers can’t bid directly on these new exchanges, just as you can’t bid or transact directly through the New York Stock Exchange.

After all the exchanges conclude their auctions, they send the highest bid back to the newspaper’s ad server. This sell-side middleman should then declare the highest bidder the winner of the newspaper’s ad space. That winner’s ad is then fetched and displayed to you on the page just in time for the page to finish loading. You probably didn’t notice anything happened at all: you just see advertisers’ ads alongside that recipe you are reading about.

LP: What is Google’s role in this advertising market? How did it influence what happened when I was online?

DS: Google operates the largest sell-side middleman, the ad server, the largest exchange, and the largest buy-side middlemen that bid on exchanges on behalf of advertisers large and small. This means that Google’s sell-side determines whether and how to route the newspaper’s ad space to the different exchanges. Google’s exchange then determines whether and how to let various buy-side middlemen representing advertisers bid on the ad space. Because Google has an overwhelming share of the buy-side market, this means that Google can often be the biggest bidder in Google’s own exchange.

LP: How important to the company are Google’s advertising activities compared to its search model?

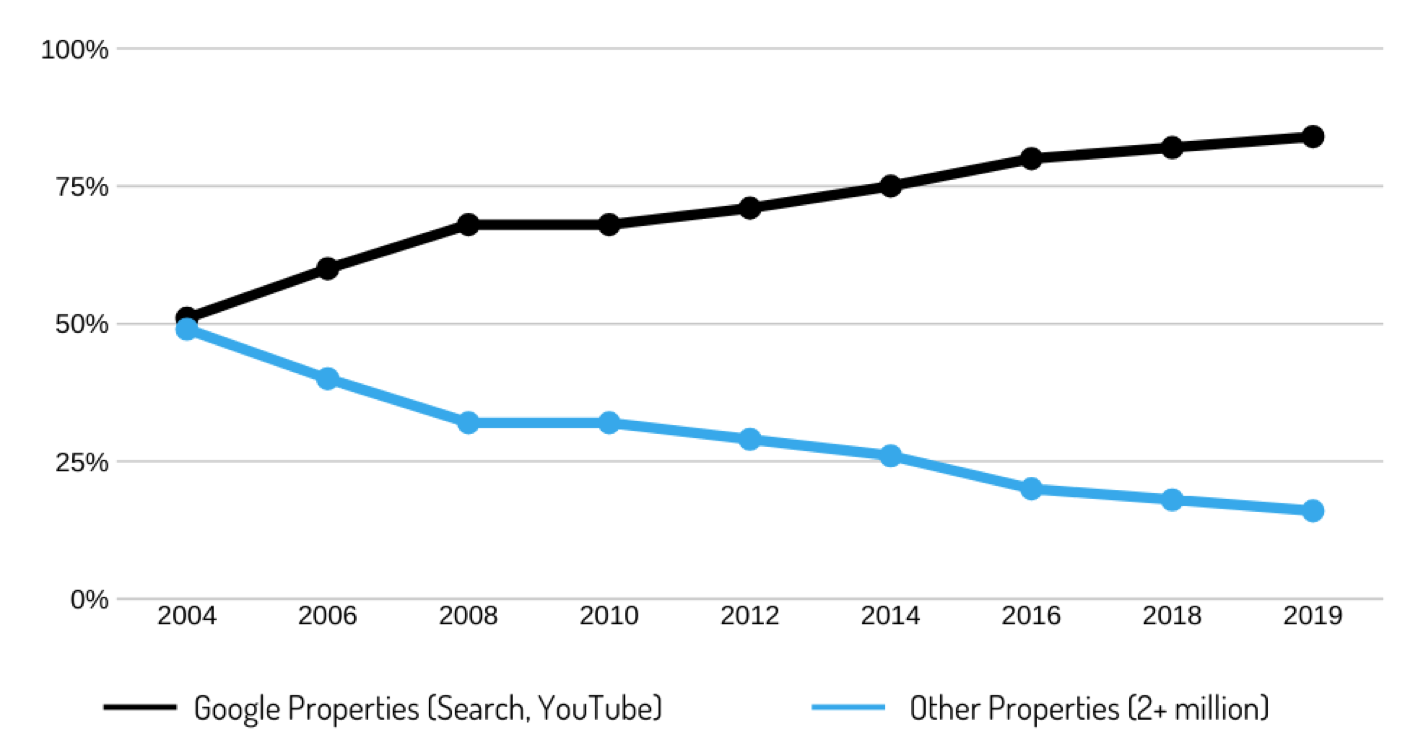

DS: Pretty important, as a graph[1] from my recent paper in the Stanford Technology Law Review illustrates. The critical thing to note here is that by owning the sell- and buy-side of the wider advertising market, Google can steer or allocate trades to its own properties, like Google search or YouTube. Trade allocation problems are also common in financial markets.

“Share of Google Ad Revenues Going to Google vs. Non-Google Properties 2004-2019”

LP: It’s not difficult to see how Google’s dominance of online searches might harm me: When I search for something online, Google can show me what it wants me to see, like a service it owns. But how do I get harmed by what Google is doing vis-à-vis online advertising?

DS: The invention of electronic trading is supposed to make the process of trading more efficient: less running around, less paper, fewer phone conversations. In the online advertising market, when an advertiser spends a million dollars purchasing ad space trading on exchanges, collectively, the trading intermediaries take 30-50 percent of that. So, the newspaper has to forgo a 300,000-500,000 dollar commission on those one million dollars-worth of ad trades. That’s a lot for an electronic trading market.

Consumers ultimately suffer, too. When newspapers have less money to invest in content or payroll, people have to pay more for subscriptions or newspapers go out of business and consumers have less news. Neither end is good for the business of news or democracy. And, when advertisers pay more for that ad space that they are buying, those costs are ultimately passed onto consumers in the form of higher prices for goods and services.

LP: You point out that Google gets away with all kinds of stuff that companies in other electronic trading markets are prohibited from doing. In financial markets, for example, we have rules against front running, insider trading, and order flow routing. Why is Google able to do things they can’t?

DS: Because we have not yet imposed trading rules in online advertising markets. There are no rules. We don’t regulate conflicts of interest. So, everything that does not fly on Wall Street, can possibly fly in ad markets. For example, for a long time, Google’s sell-side intermediary, DoubleClick, preferentially routed publishers’ ad space to Google’s exchange, even though Google’s exchange charges more than other exchanges. Google’s exchange also preferences Google’s buy-side bidding in Google’s exchange, with speed and information advantages. That also distorts competition.

LP: You’ve suggested that we could tackle failures in the online ad market by taking a few pages from the financial market regulation playbook. How would that work?

DS: We need to manage conflicts of interest: The company that runs an exchange can’t also operate on the buy- or sell-sides of the market. Alternatively, require those companies to have firewalls between business divisions, prohibit data leaking from one division to another, and prohibit the preferential routing of order flow. That is, manage those conflicts. But managing conflicts, as opposed to simply prohibiting them, would be a bigger lift for governments. For that reason, I think the first approach is superior.

LP: What are the biggest challenges to this type of regulation?

DS: I’d say politics.

There are also some changes related to browsers and privacy in the industry that present new challenges. Google’s Chrome browser will start to handle some of this ad trading process. So, after we implement those conflicts of interest rules between the buy- and sell-sides, and the exchanges, we now have a browser problem. How should we think about this? I think the answer here should follow the same path: We need to manage conflicts of interest, either through structural separations or conflicts of interest regulation (firewalls, etc.), and require disclosures and trading transparency.

Footnote

[1] Reprinted by permission of the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University, from the Stanford Technology Law Review at 23 Stan. Tech. L. Rev._(forthcoming 2020). For information visit: https://journals.law.stanford.edu/stanford-technology-law-review. Also, see: Srinivasan, Dina. “Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets,” Stanford Technology Law Review

Vol.24:1 (2020): 122.

It all sounds quite complicated. But supposing Google disappeared wouldn’t there still be the problem of trying to advertise on a medium that is far less advertising friendly than, oh say, a full page ad in the print NY Times? Bring in smartphones and you have ads that are tiny indeed.

Plus unlike readers of that print NYT, online readers have the option of blocking ads entirely and, as mentioned on this site, there are great questions about the honesty of the readership claims that Facebook, for example, supplies to advertisers.

So, reform away but here’s suggesting that print is gone absent subscriptions and therefore the ad question is a sidebar.

You may think it does not make sense, but the proof is in the pudding: advertisers spend gazillion coin to appear in those tiny screens. It must have been a surprise to Page and Brin too.

Eves 2/22/2021

Yves and Dina are absolutely correct. The traditional methods for controlling markets should be applied here. But Dina is also correct when she says the problem is political. The public wants stories with easy-to-understand narratives and complex issues with layers of abstractions are hard to describe. Identifying the small-owner victim to personalize this might help.

So I see two paths forward; the courts and congress. In the case of the courts the states’ antitrust cases seem to be the venue and the usual court “slow-walking” is the problem. The courts hate to be laughed at, so maybe a campaign built around “America held hostage by the courts, day 127”, complete with pictures of the judges leaving for work at 9 am, the daily schedules- and the pictures of the family ski vacations A La Ted Cruz. Make the judges and their behavior the story.

Congress is a more complex issue. I don’t know who in the new Democratic majority has reason to act. Who appoints the committee chairs? Who decides when the Senate or House committees will schedule televised hearings? When I worked in DC I knew the answers, but no longer.

However I’m sure there are junior and mid-level congress members in both parties raring to go.

My decision to not capitalize judges, congress and the like is intentional.

The problem is with those traditional methods for controlling markets. As the article notes –

Well yes, we do, but are those rules consistently enforced? Judging by the casino that passes for a stock market these days, I would argue that no, they are not enforced.

These companies should be broken up using anti-trust but I doubt there is the political will to do so. I think the only way that dynamic changes is when enough other businesses get fed up with being raked over the coals and being overcharged for advertising. That might produce the “political will”, but it will come in the form of bribes to Congresspeople, and we’ll have to hope Google and FB don’t just pay bigger bribes to stop any regulation. It’s ‘kaching’ either way for Congress in that scenario so the odds of them doing anything based on principle are slim to none.

What I do know is that when glorified ad agencies are the biggest, baddest economic and political actors as opposed to companies that actually produce goods and services, something is severely out of whack with how our society currently operates.

lyman alpha blob:These companies should be broken up using anti-trust but I doubt there is the political will to do so.

Quite. The reality is, Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Apple are now what, post-GFC, Tim Geithner framed the TBTF U.S.-based banks as being — international instruments of American power, however much folks like Matt Stoller dream about anti-trust legislation being used against them.

The big tech companies are arguably the last such instruments the rapidly-declining U.S. empire can claim, in fact, given the U.S. military’s poor record in winning wars.

Simultaneously, these companies have the capability to relocate their headquarters to Ireland or wherever, and go fully international, maneuvering themselves out of range of Washington’s strictures to some greater or lesser extent. Then, Google is fused at the waist with the U.S. acronym agencies, and Amazon and Microsoft aren’t far behind, whichever of them gets the Pentagon’s cloud services contract. They can also out-pay any other bidders to buy the legislation — or lack of it — they want.

And finally, though lots of NC readers will dislike the idea, all these companies — except for Facebook — do actually provide value. To such an extent that, for instance, if Amazon and all its works — the fulfilment warehouses, the deliveries, the cloud services, as well as things most people aren’t even aware of — suddenly vanished from the face of the Earth, much of the actually existing civic structure and non-finance economy of the U.S. would struggle mightily and maybe even collapse for a while.

So it’s pretty to think that Washington could bring these companies to heel as Microsoft and B. Gates once were, but it’s a different world. It almost certainly ain’t going to happen.

Except for Facebook.

Facebook is purely parasitic. Nobody likes them — not Silicon Valley, not DC, not other governments, not other businesses that suffer from their predations, and not many of us citizens. So there’s a not negligible chance that Facebook might get used as a scapegoat for all the tech companies and will get thwacked with some anti-trust legislation in DC.

There is also the problem of censorship. Paul Jay has just been BANNED from advertising on google completely for doing real journalism: https://theanalysis.news/commentary/google-bans-theanalysis-news-from-advertising-on-youtube/

Apparently Jay’s questioning of who was responsible for the understaffing of police at the Capitol on 1/6/21 was an egregious violation of Google’s policies. Jay was the lone voice asking this important question, aside from a couple of twitter posts by Aaron Mate.

Mission accomplished. I believe it was Caitlin who said these “gatekeepers” are a way of Congress controlling speech while pretending the censorship was their idea. If true that means Facebook and Google aren’t going anywhere. Perhaps that’s the reason Zuckerberg seems unfazed by Australia (although now allegedly negotiating).

Glenn Greenwald : ‘Congress Escalates Pressure on Tech Giants to Censor More, Threatening the First Amendment’

In the longer term, it’s not unreasonable to expect that as China ascends in power and influence in the coming decades, features of the Great Firewall of China will be copied — or just bought outright — from China by other states’ governments, and implemented in those countries.

Right it was Greenwald who made the stealth govt censorship via tech company argument….getting my gadflies mixed up.

And arguably the tech companies don’t want this role and shouldn’t want this role but are playing along because they are vulnerable to the antitrust attack and know that Congress has the power to do them a great deal of harm. If Congress says we will leave you alone on antitrust if you do what we want on censorship then that would probably be the definition of a “corrupt bargain.”

Also it isn’t glib to say “Congress” because both parties seem to be onboard the fake news train although Repubs are offering more pushback at the moment than Dems.

How much did Google contribute to each of our Beloved Political Parties in the most recent election?

I doubt that is a complete accounting.

from Paul Jay

Google Bans theAnalysis.news from Advertising on YouTube

https://theanalysis.news/commentary/google-bans-theanalysis-news-from-advertising-on-youtube/

Alphabet/Google have been busy de-platforming Paul Jay and Thomas Frank for some time. They appear to be testing the waters in order to take-out left-wing critics of the Democrats, such as David Sirota, Matt Taibbi, Krystal Ball, David Dayen, Yves Smith, et al.

The “tell” is the complete lack of response from YouTube to Paul Jay’s appeals. This is simply a naked power play. They claim to have “process” and “policies,” but they really don’t. Criticize their monetization of our thoughts, and you’re out.

https://theanalysis.news/interviews/youtube-censorship-and-now-whats-happening-in-kansas-thomas-frank/

otoh

But that’s from 2017…