Have you, I ask the cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, ever seen a memorial to the Holocaust – or to any atrocity – that was effective?

“It’s difficult to say how effective it is on the person who looks at it,” she says. “I mean I was in it, after all, I’m a survivor of it. Nothing really can come anywhere near what actually happened, you know.”

I ask this question because Lasker-Wallfisch strongly objects to the Holocaust memorial and learning centre that is proposed to be built in London’s Victoria Tower Gardens, just up the Thames from the Houses of Parliament. Her opinions should count for something in the ongoing debate following last autumn’s public inquiry, the outcome of which is due next year. She spent 10 months in Auschwitz, only surviving because a cello player was needed for the women’s orchestra, a group that had to play marches for the camp’s enslaved labourers and concerts for the SS. Aged 19, she was then sent to Bergen-Belsen, which was liberated just in time to save her life.

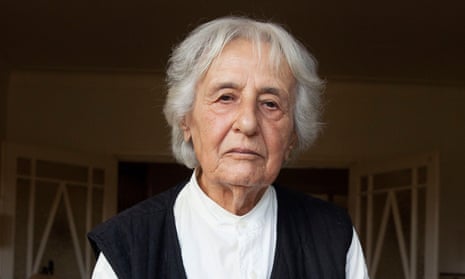

Now 95, she smokes liberally and asks me to remove my mask – after everything she has experienced, you might say that she’s entitled to take some risks. She speaks with clarity, humour, humanity and a certain toughness. The memorial, she says, is in the wrong place. She points out that it will obstruct a significant amount of the gardens, created in the 1870s as a public space with the help of a donation from the bookseller WH Smith. The construction works would endanger the lives of trees that are a century old. The partly underground complex would be, according to the Environment Agency, at risk of flooding.

Lasker-Wallfisch questions the £100m cost – “an unbelievable amount of stupid money spent on what, exactly?” – in straitened times. The proposal will “overshadow a memorial on banning slavery”, a neighbouring Victorian tribute to the abolitionist Thomas Fowell Buxton. “It hasn’t been thought through… it’s counter-productive… Basically, if you want to promote antisemitism, this would be the thing to do,” she says.

Her opposition is not, it should not need saying, because she thinks that the Holocaust should be forgotten. On arriving in Britain after the war, she found that people didn’t ask her much about it: “People had this sort of fear. I can quite understand that. I mean what do you say to somebody: ‘I hear you’re just coming out of Auschwitz… ’ It was not a conversation piece.” But eventually she started telling her story. In 1996 Lasker-Wallfisch published a book, Inherit the Truth, which at first had been intended only for her children.

By then she had overcome her aversion to returning to Germany, when the English Chamber Orchestra, with whom she played, toured near Belsen. “The orchestra were terribly worried that I would go and shoot everyone. I said, oh nonsense, I just want to see what has become of that place. And from that visit developed a completely different attitude.” She met generations who had grown up after the war. “I don’t think you can put labels on people. I have met some fantastic Germans. That’s how it should be.”

After her book was published, she started to recount her experiences in schools, including in Germany and Austria, and continued to do so until the pandemic got in the way. She believes now that the crucial task is “teaching – you’ve got to teach”. She thinks that a centre should be created to educate not just about the Holocaust but about Jewish history and its repeated experiences of expulsion and oppression. “There is a complete ignorance about who these people are. One shouldn’t even say Jews, but people of Jewish origin. We are so different from each other.” Her own family used to put up a Christmas tree in December as well as a menorah. It was “perfectly OK to coexist until 1933, when, suddenly, certain families wouldn’t allow their children to come to our house”.

Evidence of modern ignorance includes, for her, Jeremy Corbyn’s initial failure to see what was wrong with an antisemitic mural, painted in 2012 near Brick Lane in London. She speaks of “the mere fact that he didn’t think that that horrible mural was offensive, in which rich Jews are shown sitting with other people underneath them. It shows how superficial people’s thinking is about the Jews.” She also cites the idea, expressed by the late Roald Dahl and still in circulation, that Jews should have fought back harder against the Nazis. “Have you any idea? How you could have defended yourself? As a survivor, I don’t expect people to understand what it has actually been like to be in there, but don’t make clever remarks about what we should have done. It’s laughable, laughable.”

The proposal for the UK Holocaust memorial includes a learning centre. In theory, this might meet Lasker-Wallfisch’s wishes for education, except that the constricted site of the gardens has led to the omission of an auditorium, classrooms and other elements that were originally going to be part of the brief. She doesn’t know why the learning centre cannot be attached to the Imperial War Museum, where there is more space. It already has a “fantastic” Holocaust exhibition, whose collection includes the red angora sweater that Lasker-Wallfisch managed to conceal during her time in the camps.

She’s also sceptical about some of the statements that have been made about the themes of the memorial and learning centre: for example, that it will be about “British values”. She’s keen to stress that “the best of British is fantastic. I wouldn’t live anywhere else.” But “if we are very honest, what do we mean by British values? Ten thousand children [in the Kindertransport], and then the orphans that were let in after the war. Fair enough. Very nice. But what about the parents of those children?” Her own father (“such an anglophile”) vainly pleaded with British bureaucracy for admission before the war. In 1942, he and her mother were taken away from their home in Breslau (now Wrocław in Poland) and she never saw them again.

Although she has limited faith in the power of memorials, she doesn’t oppose the wishes of others, including other survivors. “Everyone should have what they want,” she says. But the planned location “is against every reason”. And there is a need for something more than remembrance. “If you remember on 27 January,” she says, referring to the date of Holocaust Memorial Day, “then you forget on the 28th.” What she wants is for people truly to understand why the Holocaust happened, so that nothing remotely like it can happen again.