The production designer Peter Lamont, who has died aged 91, worked on every James Bond film between Goldfinger (1963), the third in the series, and Casino Royale (2006), the 21st official instalment. He was absent during that time only from Tomorrow Never Dies, which clashed with James Cameron’s Titanic (also 1997). It was Lamont’s work on the latter which brought him an Oscar, following nominations for Fiddler on the Roof (1971), the Bond adventure The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) and Cameron’s horror sequel Aliens (1986).

As he moved up the ladder from draughtsman to set decorator and art director before finally being appointed production designer on For Your Eyes Only (1981), Lamont became a prized member of the Bond family. “I so admire Peter and his colleagues,” said Roger Moore in his 2008 autobiography My Word Is My Bond. “They make the impossible possible and the unbelievable believable.” Michael G Wilson, who with Barbara Broccoli took over the producing reins from Broccoli’s father, Albert, said: “The first thing we do when we start working on the script, and we’re thinking about locations and whether we can do this or that, is we call up Peter Lamont.”

His responsibilities on the series were wideranging and unpredictable. On Goldfinger, he was recruited by the great production designer Ken Adam to help design Fort Knox. For the sea-bound Thunderball (1965), he took a crash-course in scuba-diving after Adam told him: “You’d better learn to swim underwater.” The film, shot partly in the Bahamas, also required him to spend time at RAF Waddington studying a Vulcan bomber in preparation for building a 14-ton replica which then had to be shown sinking at sea.

One of his most challenging assignments came as one of the art directors on The Man With the Golden Gun (1974). The night before he left for the Thai island Khao Phing Kan, the production designer Peter Murton told him to be prepared to stay for some time.

“I came home seven months later,” he told Matthew Field and Ajay Chowdhury for their Bond encyclopedia Some Kind of Hero (2015). “It was a place that was undeveloped at the time. Believe me, the Bonds have always been first in these places. I was the one who ran everything. Telephones didn’t work. Telexes took three days, and a letter – God knows where it went.”

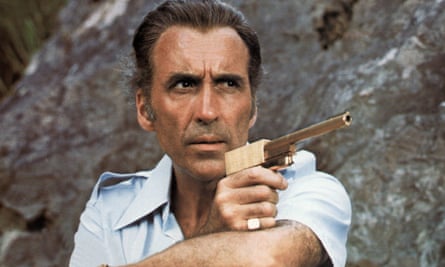

He also taught the actor Christopher Lee to assemble the golden gun brandished by his character, the villain Scaramanga, and comprised of everyday objects such as cuff-links, a lighter and a fountain pen. Lamont commissioned the prop from the London jeweller J Rose when the one supplied by Colibri, the credited jeweller, proved unusable.

After the soaring costs of Moonraker (1979), which hitched itself to the Star Wars bandwagon, the series went back to basics with For Your Eyes Only, for which Lamont stepped into Adam’s shoes. John Glen, the film’s director, said: “He was reaching a stage in his career where we were either going to promote him to production designer or he was going to leave the fold and do his own films for someone else because he was that good you couldn’t ignore him anymore.”

Lamont produced impressive sets resourcefully; the ceremonial barge in Octopussy (1983), for instance, was constructed from a pair of abandoned boats which he found on the banks of Lake Pichola in Udaipur city in India. He also came to the rescue in 1984 when the 007 stage at Pinewood burned down following an accident on the set of Ridley Scott’s fantasy adventure Legend. Within 12 weeks, Lamont had overseen the reconstruction of what was now renamed the Albert R Broccoli 007 Stage, and had parcelled out sections of the latest Bond production, A View to a Kill (also 1985), to other stages.

To avoid the bureaucratic complications of filming a tank chase in St Petersburg for GoldenEye (1995), he proposed building sections of the city at Leavesden studios. Judi Dench, cast in that film for the first time as the intelligence chief M, singled out for praise “the flat Peter Lamont designed … this gorgeous apartment in Canary Wharf”. On Casino Royale, he designed over 40 sets, from the casino’s salon privé to the building site where the film’s spectacular parkour pursuit was staged.

Lamont was born in London, the son of Mabel (nee Curtis) and Cyril Lamont. His father was a signwriter who sometimes worked at Denham film studios, in Buckinghamshire, where Lamont visited him regularly and later got a job as a runner. After two years in the RAF, he returned to Denham and worked as a junior draughtsman for more than a decade. He progressed to set dresser on films such as The Bulldog Breed (1960) and Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life (1964), and was assistant art director on Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968).

Other art-directing credits include Sleuth (1972), starring Laurence Olivier and Michael Caine, and the Nazi-hunting thriller The Boys from Brazil (1978), also with Olivier. As production designer, he worked on the wartime spoof Top Secret! (1984) as well as continuing his collaboration with Cameron on the action comedy True Lies (1994).

It was Bond, though, which dominated his life, as reflected in the title he chose for his 2016 autobiography, The Man With the Golden Eye: Designing the James Bond Films. In it, he revealed that he had not intended Casino Royale to be his swansong, and had met with the director Marc Forster in the hope of designing the next film in the series, Quantum of Solace (2008). “I sensed that he was wary of working with someone 40 years his senior,” Lamont said. “Perhaps more seriously, I think he suspected I would be more sympathetic to the producers than to him.”

In 1952 he married Ann Aldridge; she predeceased him. Lamont is survived by their daughter, Madeline, and son, Neil, an art director and production designer who worked with his father on several films including GoldenEye and Titanic.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion