A dangerous-looking porcupine scuttles across the bottom of a page of a medieval manuscript, amid scenes of fire-breathing dragons, bodies bubbling in cauldrons, and boats deluged by biblical floods. Known as the Lambeth Apocalypse , this 13th-century illuminated text is one of the lurid highlights of the magnificent collection of Lambeth Palace Library , the most important religious archive in the UK and the largest in Europe, after the Vatican in Rome. For centuries, this precious hoard has been kept in a series of leaky, draughty rooms in the palace, gradually filling up every cramped corner. Now, after 400 years, it finally has a purpose-built home – and it’s safe to say that, if the apocalypse ever comes to south London, this fortified building will probably survive it.

“Noah could float past in his ark and the collection would be all right,” says Clare Wright, the Scottish architect behind the £24m new library. “We’ve created a concrete bunker with more bunkers inside, all lifted up above the one-in-1,000-year flood risk level.”

As bunkers go, it is pretty refined. Clad in a sober costume of red bricks, the building stands as a proud bastion at a bend in the busy Lambeth Palace Road, its nine-storey tower poking up above St Thomas’s hospital to peer over at the Palace of Westminster across the Thames. It meets the street with a sheer redbrick cliff-face, its monolithic mass punctured only by a few tiny square windows and the steel gates of a dark grey entrance. Crowning it all is a covered terrace with the air of a rooftop lookout station. This is a public facility, but its primary purpose is clearly the security of the collection. All that’s missing are the cannons.

“Protecting the archive was our main priority,” says library director Declan Kelly. “One of our new trustees asked where the cafe and shop are going to be, but we don’t have either. There’s a little room for readers to make themselves a cup of tea and a small exhibition space, but the emphasis is on safeguarding the collection.”

The precedence of manuscripts over people is evident in the building’s utilitarian look: this is a librarian’s functional machine for conserving, cataloguing and storing, to which readers also happen to be granted access. From a distance, it could be a Crossrail ventilation shaft, or a service wing for the massive hospital across the road, but the austere feeling is clearly intentional. “There’s a moral imperative that the building is long-lasting and well-built,” says Wright, “but that it’s not extravagant or indulgent.”

It might seem like a blunt arrival to such a sensitive location, but the project is merely the latest stocky tower to be added to the sprawling palace grounds. The official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury has grown over the last 800 years , as each successive bishop left their mark. It began in the 13th century with Stephen Langton, whose chapel still stands here, now overshadowed by the rough ragstone walls of Lollards’ Tower, added in 1435 and later used as a prison, and the imposing redbrick battlements of Morton’s gatehouse, built in 1495. Set at the other end of the palace grounds, in a neglected corner of the garden, the new library rises several storeys above the existing palace towers, holding its own as a sturdy presence on the skyline.

“We wanted the building to feel like part of the garden wall,” says Wright. “It’s the new ‘portal of knowledge’ to complement the other palace gates.” Her practice, Wright & Wright, won the project in an invited competition, beating major international names including Zaha Hadid and Herzog & de Meuron, in part because they were the only firm to push the building right to the edge of the site in order to occupy less of the garden. Their big brick castle forms a bulwark against the main road, protecting the palace garden and sheltering a new landscape around a pond, designed by Dan Pearson Studio.

Another key factor in the architects’ favour was their reputation as library specialists. They have long been firm favourites of Oxbridge colleges, creating sensitive homes for the libraries of Corpus Christi, Cambridge, as well as Magdalen and St John’s in Oxford. All are careful additions to historic settings, cleverly stitched into difficult sites, where much of the character comes from what was already there. You can sense they are rather less comfortable with being given the responsibility for an entire standalone building of this scale. In places it feels generic, at odds with the special quality of what it houses, with rather too much of the default palette of oak veneer, grey steel and white ceiling tiles.

From the main entrance, a shelf-lined reading room enjoys views out on to a grove of mature trees, with high-level mirrors creating the illusion from within that you are reading in the middle of a forest. Responding to security concerns, the room is also arranged around clear sight-lines from the supervisor’s desk, with added surveillance from offices above. A single-storey conservation wing extends out into the landscape, framing the other side of the pond and providing the conservators with world-class facilities – a boon compared to their previous cramped attic quarters. There are also a number of teaching and meeting rooms, where the archbishop can hold more confidential meetings away from the palace. The rooftop eyrie, meanwhile, is designed as a seminar room, but it has also clearly been conceived with private hire in mind, given the spectacular views from the summit. Public access to this level will sadly be limited to one day a month, mainly due to the additional management required for such a high-level open-air space (with the tragic events at Tate Modern still in recent memory). But the biggest practical improvement is simply bringing everything together under one roof.

“It makes a dramatic difference to what we had before,” says librarian and archivist Giles Mandelbrote. “When we were in the palace, precious items from the collection had to be wrapped in plastic bags and carried across the courtyard through the rain to get to the reading room.”

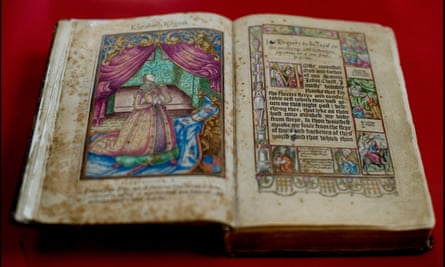

Carrier bags might be fine for Penguin paperbacks, but they’re not ideal when you’re dealing with priceless medieval scripture. Mandelbrote is currently finalising a selection of highlights from the collection, to be displayed in a series of vitrines on a mezzanine level above the entrance, when the building opens to the public in spring, and the potential range of material is astonishing. There is the ninth-century pocket-sized gem of the Macdurnan Gospels; the vast and lavishly illuminated Lambeth Bible; the only surviving copy of the execution warrant of Mary Queen of Scots; and the gloves worn by Charles I on the scaffold. There are also items that provide a window on to some of the stranger things that preoccupied the bishops of times past. One 16th-century pamphlet titled “The Apprehension and Confession of Three Notorious Witches” includes passionate debate over whether the black dog used by one alleged witch to execute her malice upon her enemies did, or did not, have the face of an ape. There is also a 17th-century silver dagger from the era of the Popish Plot, described as “possibly a special edition for the spectacular pope-burning procession in London in 1679”.

It is a useful reminder of the library’s origins. It was given to the nation by Archbishop Richard Bancroft in 1610, an era when the Elizabethan religious settlement felt under attack, from Roman Catholicism on one hand and the Puritans on the other. In this age of fierce controversy, when theological differences were argued in print, such libraries were founded as literary arsenals. With their substantial new building, the Church of England has a mighty repository to preserve its ammunition from fraught centuries past – with an additional 20% of storage space awaiting whatever the future holds.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion