Forbes died on December 9, at age 86. He won the 1955 French Open (partnering Darlene Hard) and reached another final at Roland Garros in 1963, this time in the men’s doubles partnering Abe Segal, his long-time on-court companion. After retiring, he wrote several books, including “A handful of summer” and “Too soon too panic”, published in 1979 and 1995, respectively. In 1959, Ubitennis founder Ubaldo Scanagatta was on scoreboard duty as a teenager during the Davis Cup tie between Italy and South Africa in which Forbes played both singles and doubles. What follows is a rememberance written by Gordon’s friend Joseph B. Stahl (also the author of the drawing above), whereas here can be found the tributes to Ralston and Olmedo.

Gordon L. Forbes of South Africa, an Inadequate Memoir of a Master Raconteur and a Helluva Tennis Player by Joe Stahl

I first met Gordon in August 1962 when we both played in the grasscourt Meadow Club Invitational Tennis Tournament at Southampton, Long Island, N.Y.; it was a lead-in event to the U.S. Nationals at Forest Hills. I really wasn’t good enough to be in that tournament, but somehow Grenville Walker, who ran it, let me in the draw. I was paired against Gordon in the first round and really had no idea who he was, although he’d reached the third round at Wimbledon only a few weeks earlier.

On the morning of the Monday on which the tournament began, I was practicing on the Meadow Club’s grass with Arthur Ashe when Arthur called me to the net and, pointing to a tall fellow three courts down the way, told me, “That’s your first-round opponent.” Gordon was practicing with a skinny kid who looked like Gordon had taken him out of his pocket and unfolded him; it was Cliff Drysdale.

Gordon didn’t look like much to me—mind you, I didn’t think I could beat him, but I thought we’d have a reasonably competitive match. Unfortunately, however, I made the dreadful mistake of practicing so long and so hard with Arthur the whole morning (at one point Arthur told me, “If your forehand were as good as your backhand, you’d be great”—you see, it was the one day a year that I could hit a backhand), that by the time my match with Gordon began that afternoon I was exhausted, and Gordon beat me -love and -love.

The diminutive but very famous New York Times tennis reporter Allison Danzig was in the stands—he had come all the way out to Southampton from Manhattan to cover the match—, and I remember his withdrawing a small notebook from his pocket when it began, but after only a few games, he put it back into his pocket and never took it out again. As Gordon and I shook hands at the net at the end of the match, I said to him, “Damn, Gord-o, I thought you were a gentleman. Don’t you know that a gentleman always lets an overmatched opponent win at least a courtesy game? It’s like it says in the Bible, never punish a man with more than 40 stripes ‘lest thy brother seem vile in thy sight.’ ”

Gordon thought reflectively for a moment and in one of those great philosophical inspirations he often had, he gently instructed me, “Joseph, that is all very well for religion, but tennis is different: In tennis it is a law that you should always beat your opponent as badly as you can.” And that generously imparted wisdom was the beginning of a friendship that lasted for decades.

We corresponded after that, and in 1979 when I read his book A Handful of Summers, I saw that, in it, he claimed he had lost in the first round of that Meadow Club Tournament in 1962 to Roger Werksman—not beaten me!—because he’d just gotten off an international airline flight at JFK Airport and driven all the way out to Southampton and was tired. So I sat down and wrote Gordon a letter on my legal stationery (I conducted a long masquerade as an attorney at law, 1963-2004) in which I told him I was going to file a wrongful-death lawsuit against him for prematurely canceling me out of existence, and I enclosed a copy of the Meadow Club draw showing that he’d beaten me in the first round, “6-0, 6-0.” I ended the letter, however, by telling him that all would be forgiven if he would buy me a drink whenever we might meet at Wimbledon, this was agreed between us, and for a long time he would invite me into the Last Eight Club at Wimbledon every year, “Gord-o” would buy me a drink, and we would have a lot of amusing chit-chat with the other characters hanging around in the Last Eight.

At the time I read his book, I was so taken with the comedy, the charm and the sense of it that I decided to buy seven copies of it to distribute to friends as Christmas presents. At that time, Russell Seymour, who had played on the South African Davis Cup team with Gordon, was the tennis professional at the New Orleans Lawn Tennis Club, and I asked Russell where I could find copies of the book. He told me that Gordon’s sister Jean, who lived in Texas, had a supply of them, he gave me her phone number and address, and after speaking with her by phone, I sent her a check and she sent me the seven books accompanied by a charmingly reminiscent letter about tennis people we both knew.

It was so shortly after that, only a day or so, that the news broke that Jean had died, that I thought her letter to me might be the last one she’d ever written, so, after photocopying it, I sent the original to Gordon in South Africa, knowing he would like to have it. Gordon’s second book, Too Soon to Panic, which of course I also read, was really an extended letter to Jean in her afterlife, and not long after its publication, Radio Wimbledon, the All England Club’s radio station for which I worked as a commentator, interviewer and talk-show participant, asked me to interview Gordon about the book, which I did. It is one of the best interviews I ever conducted, because I knew Gordon so well from his books and from personal acquaintance, so I knew what cues to give him to enable him to say everything he wanted to air.

Another incident about A Handful of Summers comes to mind. In, oh I guess, about the mid-1980s, I was visiting a doctor friend in Miami who took me on his hospital rounds with him one day. As we were navigating the hospital’s halls, a doctor stopped us and told my friend that if he wanted to see the most gorgeous collection of women ever assembled, to go to such-and-such a room, because there was an endless procession of beauties constantly coming there to visit a particular patient. So we went, and the patient turned out to be the French tennis player Jean-Noël Grinda, who was there for a coronary angioplasty.

None of the fabled women were there, but I asked Jean-Noël if he had read Gordon’s book A Handful of Summers, at which he groaned and said, “Ohhh, I have terrible memories of Gordon Forbes!” “Why is that?”, I asked him. “Because,” he said, “Gordon beat me 7-5 in the fifth set at Bournemouth one year after I led him 5-1, 40-15 in that set.” So I told him, “Listen, I am going to send you this book Gordon has written, and I swear that when you read it, you will actually like Gordon Forbes.”

The upshot of it was that I sent Jean-Noël the book at the French address he gave me, and Jean-Noël wrote back to me telling me he enjoyed the book and appreciated my sending it to him so much that he was reconciled to Gordon, and Jean-Noël invited me to stay at the Hotel Westminster Concorde on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice, which Jean-Noël owned, any time I wanted, for free. Alas, I never had a chance to take him up on it, but that is a tribute to how good the book is.

One thing that struck people about Gordon, not least me, was that he never seemed to age. Decades would go by, yet Gordon still looked exactly the same as he always had. One day in 1989 I was playing tennis at Lew Hoad’s Campo de Tenis on the Costa del Sol in Spain with Heather Brewer Segal, who had been married to Gordon’s doubles partner Abe Segal. Gordon at that time was in his mid-50s. Well, the subject of Gordon came up, and Heather said, “You know something, it just isn’t fair! Gordon still looks like he’s 28 years old!” And it was true. I told Heather, “Maybe he read The Picture of Dorian Gray, and he has a portrait of himself growing old for him in an attic.”

Lew Hoad sold Gordon’s Handful book in the shop at the Campo de Tenis, and Lew used to pontificate that it was, as Lew put it in his Australian lilt, “the grytist book on tinnis evah writtin.”

Of course the real hero of Gordon’s Handful is Abe Segal, the Abe Segal, that is, that Gordon portrayed him to be, an author of zany antics who was constantly poking fun at the foibles of mankind. And that portrayal is a testimonial to how creative Gordon could be. For the “Abie,” as Gordon always referred to him, of that book is more a figment of Gordon’s lively imagination than an authentic representation of the real Abe Segal. I say that because Abie published a memoir in 2008 called Hey, Big Boy! that destroyed the entire marvelous impression of him Gordon had created in Handful. Hey, Big Boy! is so terribly written in such atrociously illiterate English and reveals Abie to be such a clumsy oaf of a character, that I wrote to Gordon telling him this and how disappointed I was in Abie’s book. Gordon, who at that point did not even know Abie had written a book, wrote back to me lamenting that “He just had to have a book.” Had Abie not written that book, he would have lived forever as the grand Falstaffian hero Gordon had painted him as.

One of Gordon’s greatest bravura performances of wit was the after-dinner speech he gave at the annual pre-Wimbledon International Lawn Tennis Club of Great Britain Ball—“the IC Ball”—at the Dorchester Hotel in London, I guess in about the mid-1990s. Gordon’s talk was so loaded with his cleverness and hilarious witticisms, tempered by his wry take on the humor of things, and it delighted his audience, including me, so much that when he stopped talking I wanted to cry because I wanted him to continue talking forever. From the moment he spoke his first sentence he had people laughing in hysterics, he was so funny, and I wished I had said the things he came up with. It was the champagne and caviar of entertainment.

But besides being a sage observer of and reporter on life, Gordon was also a helluva tennis player, for he did have wins over Hoad, Laver and Drobny.

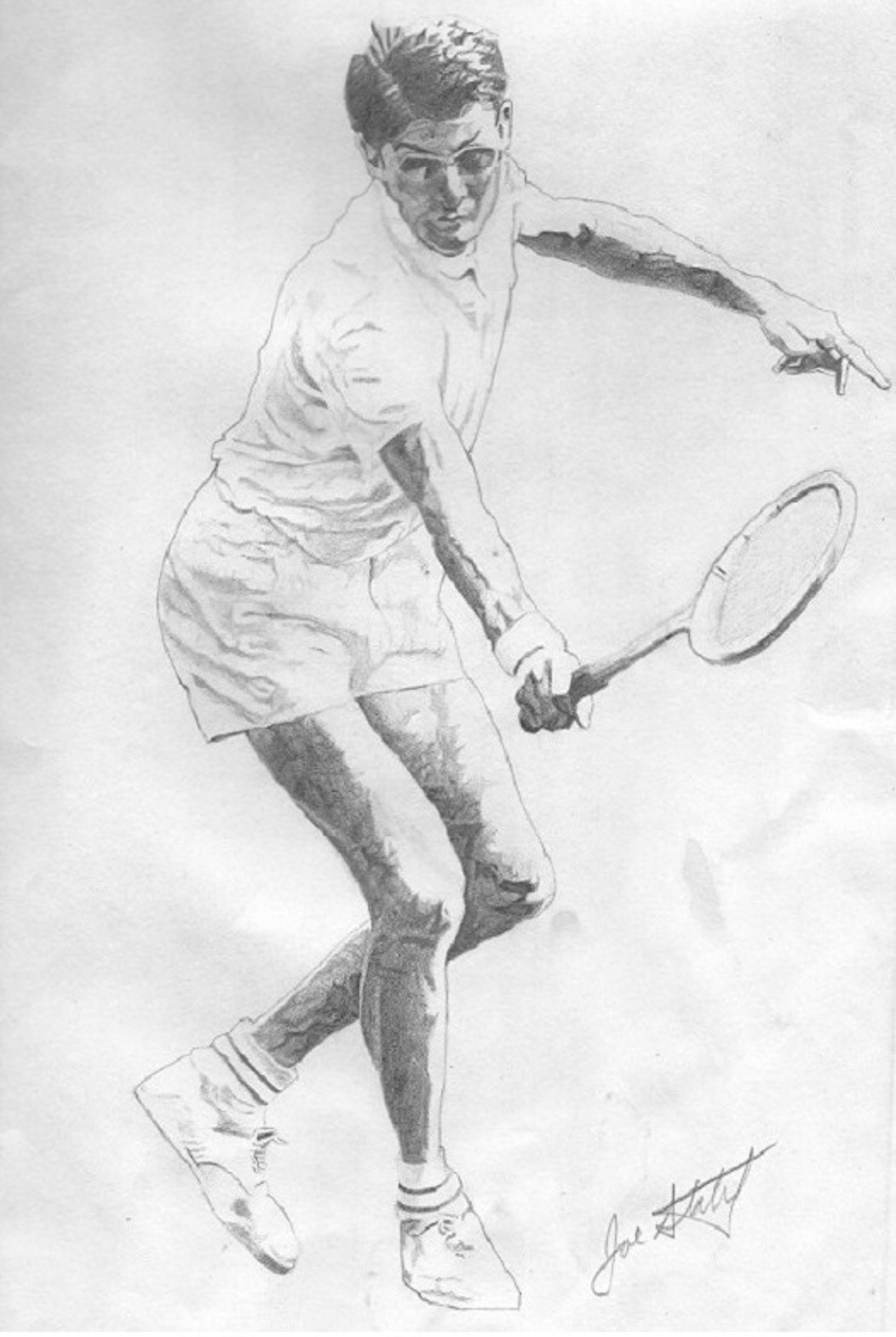

I have a bad habit of making pictures of things that strike my fancy, and in 1962 I did a pencil drawing of Gordon from a photo of him that appeared in World Tennis magazine that shows Gordon hitting a backhand. When I showed the drawing to Russell Seymour, he took one look at it and said, “That’s Forbsey’s backhand alright.” Here it is:

Joe Stahl, by his own confession, masqueraded as an attorney at law for 41 years, retiring in 2004, since which, he has done three things very badly: write; paint; and play tennis. He is hoping to get into the Tennis Hall of Fame as the worst player in the history of the sport. He and Gordon Forbes were friends for many years, exchanging good-natured insults the whole time. Joe was a commentator at Wimbledon and an editor and contributor at Tennis Week magazine.