What might be the enduring symbol of the coronavirus that turned our world upside down in 2020? Might it be those Thursday evenings of spring and summer when, at the stroke of 8pm, Britons overcame the national traits of embarrassment and reserve and ventured out on to the doorstep to applaud doctors, nurses and key workers, banging saucepans and nodding to neighbours in a synchronised “clap for carers”? Or might it be the first sign that trouble was coming this way, that footage of Italians singing to each other from their balconies in a ritual that seemed as exotic, distant and unlikely then as the very notion of a “lockdown”, back before that dramatically punitive word lost its sting?

A chequerboard computer screen of faces as Zoom became the prime means of face-to-face contact with those who didn’t live under one roof? The smaller, quieter sight of families visiting grandparents but getting no further than the garden path, toddlers waving through the glass at elderly relatives?

Or maybe something hopeful, perhaps one of those moments from the last weeks of the year that seemed to promise an ending, as scientists announced their breakthrough in finding a vaccine. It could be the pictures of Maggie Keenan, aged 90, becoming the first person in the world to get the jab. Or if a bleaker snapshot was more fitting, it might be an image of an event that recurred throughout 2020: the sparsely attended funeral, mourners kept distant from each other if they were allowed to be present at all. Or the priest in Burnley breaking down in tears as he described bringing food parcels to families so poor, their deprivation deepened by the pandemic, that the children would rip the bags open to get at the food before he’d even got through the door.

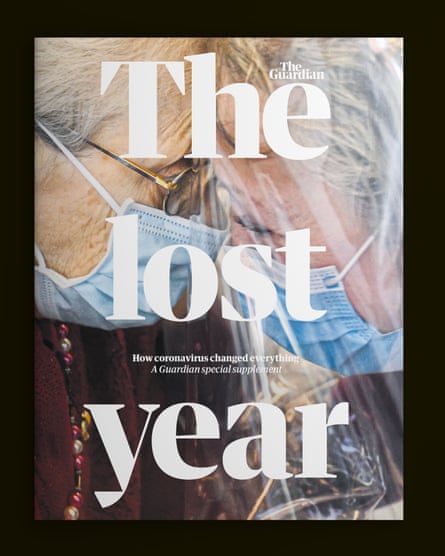

Perhaps the lasting motif will not be a scene but an object. Say, the simple face mask, an item that once seemed alien and even frightening but is now commonplace, even if it never quite stopped looking and feeling strange. Maybe it will be those signs that were tied to lamp-posts or marked out on paths in public parks, reminding us to keep 2 metres apart. Alternatively, it could be a gesture, the elbow bump that gained currency when the crisis first hit. Or maybe the symbol that will linger will be the graphic rendering of the dreaded virus itself, an attempt to make the invisible visible: that cartoonish image of a spiked ball, like a festive orange studded with cloves.

But there is another, less literal candidate. It would be apt because it would remind us what the coronavirus did to us and to our world. A fitting symbol of this global pandemic would be a magnifying glass. For while the virus ended and upended so many lives, and spawned a whole new vocabulary – social distancing, furlough, herd immunity, R number, circuit breaker, bubble, unmute – it did not remake the global landscape so much as reveal what was already there, or what was taking shape, just below the surface.

It amplified it, sometimes distorting it, sometimes illuminating it in alarming detail. Covid‑19, the disease that was first reported to the World Health Organization one year ago this month, served as a lens through which we were able to see our politics, our planet and ourselves with a new and shocking clarity. It made 2020 a year of revelation, even if what was uncovered was not nearly as new as we might imagine.

Perhaps that was most apparent at the top. Even as the virus forced billions to cover their faces, it ripped the mask from so many of our leaders. Naturally, the most lurid case was that of Donald Trump. At the end of last year, plenty of sage observers of the United States – including one, Prof Allan Lichtman, whose model had correctly predicted every election since he devised it nearly 40 years ago – believed that 2020 would see Trump elected to a second term. The economy was thriving and, despite all of Trump’s excesses, the signs were strong that he would elbow his way to victory.

But Covid magnified Trump, enlarging his faults so they became too frightening to miss. It showed him as lacking even the most rudimentary empathy: not once did he channel the anxiety or grief that his nation was feeling, even as the US death toll rose and rose. It showed him to be dishonest, insisting that the virus was about “to disappear”, like “a miracle”, that it would “go away” when the weather got warmer, that it was “fading”, that America was “rounding the corner” even though the infection rate was scaling new heights. And it showed him to have contempt for facts and science, regularly contradicting and undermining the doctors leading the US response to Covid, including the veteran specialist in infectious diseases, Dr Anthony Fauci, one of the defining faces of 2020. Trump urged his supporters to “liberate” themselves from lockdown, even as the disease was running rampant. At one point, Trump suggested Americans should fight the virus by injecting themselves with bleach.

Convinced that a thriving economy would see him win in November, he was determined to pretend that life could function as normal, that masks and distancing were for cowards and losers. Even when he was infected and hospitalised in October, after a maskless super-spreader event at the White House, that remained the message. His most devoted followers swallowed it because, for four years, they had swallowed everything, trusting him more than any expert or authority – more than their own eyes.

Of course, none of this came as news to anyone who had been paying attention. The callousness and the disregard for facts had always been true of Trump and the post-truth, anti-science information cocoon he had built for his devotees, a place where they might huddle together and stay warm. But Covid illuminated those traits of Trump’s more brightly, more lethally, than ever before, just as it confirmed the riven state of contemporary America – a country where even the wearing of a mask could become a cultural and political signifier, revealing on which side of the great divide you stood, red or blue, Donald Trump or Joe Biden, conspiracy theory or science.

And so Americans kept dying, the daily death toll rising above 3,000 in early December – each day a new Pearl Harbor, a new 9/11 – the total on course to reach 300,000 by year’s end. The economy went into reverse and Trump’s ratings refused to rise. Even in a year when Democrats in general slipped back, performing less well in 2020 than they had in the midterms of 2018, Trump lost an election he had once looked set to win. The pandemic had undone him. Under the lens of Covid, he had withered.

Trump was only the most garish example of a pattern that became identifiable across the globe. The populist loudmouths, the braggarts whose stock in trade was railing against the experts, imagining themselves to be free of the laws of factual reality, fared badly against a threat as real as the virus, a menace that could not be talked away with a rally, an insult or a joke. Several contracted it themselves, Boris Johnson and Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil succumbing early. But their countries struggled too. Both Britain and Brazil won unwanted places in the mortality top 10, measuring total deaths by coronavirus relative to population size. At the time of writing, Britain ended the year as the fifth most lethal country in the world, thanks to a death rate of 873 per million people. Germany, led by the research chemist Angela Merkel, was in 56th place, with 200 deaths per million.

Again, none of this was exactly novel. Even before the pandemic struck, it was clear that Merkel and others valued quiet, technocratic competence while Johnson’s administration was built on slogans and myths, rhetoric and promises, prizing chummy loyalty over the hard graft of good governance. But Covid put that contrast in lights.

Johnson and his team handled the crisis with an ineptitude stunning in its consistency. Even while Italians were screaming from their rooftops that the virus was coming our way and that we had to lock down, Johnson was still bragging about shaking hands and giving the green light to mass gatherings, whether at football matches, pop concerts or the Cheltenham Gold Cup – events that were all later linked to spikes in infection. Everyone with a GCSE in science knew that lockdown would have to come sooner or later, but the government chose later – a delay that, had it been avoided, would have saved at least 20,000 lives, at least according to Prof Neil Ferguson of Imperial College London.

Even once the lockdown came, there were curious blind spots. It was not total: up to 20 million air travellers flew into the UK during that first wave, unhindered by even the most basic checks. And despite government promises of a “protective ring” thrown around care homes, the opposite was true. Elderly people were discharged from hospitals and back into care homes without being tested, so seeding a pandemic within the pandemic.

Britain was slow to get hold of the personal protective equipment it needed, shelling out some £17bn in a supermarket sweep in which millions was funnelled to companies with no track record in the field but with the advantage of friends in high places. In November, the National Audit Office revealed the existence of a “VIP lane” for those would-be suppliers lucky enough to have a friend in parliament or in ministerial office. If you were so blessed, you were more than 10 times likelier than a regular bidder to hit the jackpot and bag a lucrative government contract. Again, to learn that Britain is a chumocracy where it pays to know the right people was hardly a stunning surprise. But Covid left no doubt.

It was the same story with the “test and trace” saga. Having abandoned community testing, flirting instead with the notion of herd immunity, the government then had to catch up. But the record was, once more, one of cronyism and failure. Testing apps that failed to work; tracers hired with next to no training, left idle and unused for shift after shift; a computer system that offered people tests at the opposite end of the country; stats that suggested a mere 11% of those contacted went ahead and isolated for 14 days. It was called NHS test and trace, trading off the public affection, even reverence, for the National Health Service – a civic religion whose status was magnified in this year of the pandemic – but the work was contracted out to private firms such as Serco and Sitel.

Through it all, Johnson – a leader for sunny days who found himself facing a hurricane – tried to dodge his duty to deliver bad news. Again and again, he served up false cheer. In March he said we would “send coronavirus packing” within 12 weeks. In July, he said it would all be over by Christmas. In mid-October, he rebuffed Labour calls for a second, circuit-breaking lockdown, adamant that such a move would be a “disaster”. But by Halloween he was back on TV, announcing – guess what – a second English lockdown.

It worked so well that whole areas of the country emerged from it only to be placed into a higher “tier” than the one they were in before. Ahead now is a five-day easing of restrictions for Christmas, but that relaxation was never related to any letup in the virus itself. Rather, it was born of the sense that if tighter restrictions remained in place for the holiday season, they would just be ignored. Better to adapt the law than for the law to be an ass.

Many Britons, like their counterparts in the US, spent much of 2020 lamenting their misfortune in being saddled with such woefully inferior leadership at a time when they were reminded anew how much quality at the top matters. They eyed the likes of Merkel or Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand – steady, sober, serious – just as they marvelled at the competence on display in South Korea, Vietnam or Taiwan, where the total number of deaths were 526, 35 and seven respectively (and remember, the virus struck South Korea early). The contrast with their own, supposedly “world-beating” administrations was stark.

As if to fill the vacuum, leadership came from other quarters, some of them unexpected. In the first lockdown, it was not the prime minister, itching to channel Winston Churchill, who found the right register but rather the woman whom Churchill had once served as prime minister: namely, the Queen. In a rare TV address to the nation, she promised that “We will meet again”, a nod to wartime and to Vera Lynn that simultaneously warned the country that this was as mortal a threat as war, and reminded us that we’d got through worse.

Next in line was someone more than 70 years younger. Somehow it fell to Manchester United’s striker Marcus Rashford to articulate the sentiment that a moment of peril demanded more from us, that we had to look after each other better. His campaign for the extended provision of free school meals in England to the poorest and hungriest children spoke to Britons’ better angels, and forced a government U-turn – twice.

The coronavirus also placed a magnifying lens over one fact that was true but perhaps not quite so vividly clear before the pandemic: that this is a disunited kingdom.

That was conspicuously true in a practical way: thanks to devolution, the UK became a patchwork of differing rules and regulations, so that the once-mundane business of social interaction depended on which of the four nations you were in. While a pint in a pub might be legal in England, you had to check whether it was permitted in Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland. The rule of six might allow you to host a gathering of six relatives plus a baby on one side of the border, but the baby might count as one of the six on the other. Of course, devolution had been a fact of British life since 1999. But never was the variance between the UK’s constituent nations so manifest or so intrusive into quotidian life.

Still, those were hardly the divisions that mattered most. Inequality is so entrenched, it can feel like a law of nature. Even so, the coronavirus lens managed to magnify it in new and sharp ways. US politicians like to speak of the difference between jobs where you shower before you go to work and jobs where you shower once you get home. In the age of Covid, that distinction between white- and blue-collar labour found a new form: those who could work from home, and those who couldn’t.

A gulf rapidly opened between those who complained about Zoom fatigue, laughing about dressing to impress above the waist while wearing leisurewear below, and those who had no such option – those whose places of work were shut and who suddenly feared for their livelihoods. The former saw no hit to their income: on the contrary, now that their outgoings were sharply reduced, their finances became plumper – in the first half of 2020, UK household savings rose by £100bn. For some in that category, lockdown meant baking sourdough bread, learning a language or pausing to smell the roses.

But for those on the other side of the WFH divide, especially those with jobs in retail or hospitality, contingent on actual places being open to actual people, lockdown meant waiting on furlough payments and government support, knowing that eventually the help would run out. It meant families living on top of each other, often in cramped flats that suddenly felt twice as small now that everyone was kept at home. It meant keeping children, at home from spring to autumn, from climbing the walls.

This was a global picture, the virus widening the chasm between the richest and poorest. The wealthiest got even wealthier. For the billionaire class, 2020 was a banner year, their fortunes topping $10.2tn (£7.6tn) in the summer – a giant increase on the year before, according to data from the Swiss bank UBS. The face of that enrichment was Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, whose pockets were filled by the pandemic and the dependency on home delivery it induced. In 2020 he became the first human being to have a personal fortune in excess of $200bn, that sum swollen every time someone, somewhere, preferred to click rather than don a mask and walk to a shop.

And yet 2020 was also the year Britons used food banks in record numbers and the year when thousands of cars lined up in Dallas, Texas, queueing to get help at a “food distribution event”, with some 25,000 waiting in line on a single day. Underemployment, a lack of good, secure, well-paid, full-time jobs, had long been a problem in the UK and across the industrialised west. Covid magnified that into something even bigger: mass unemployment, on a scale unseen for decades.

As Britain braced for the most severe economic contraction since the “great frost” of 1709, it was those with least who were hit hardest. According to the Legatum Institute, nearly 700,000 people, including 120,000 children, were driven into poverty in the UK by the pandemic. And because poverty is about flesh and blood, not just pounds and pence, that had lethal consequences. An analysis described by the BBC found that “the death rate from all causes between April and June in the most deprived areas was nearly double that of deaths in the least deprived parts of England.”

The divide cut across multiple lines. It was regional, with north hit harder than south: that BBC study found that most of the top 10 towns and cities with the highest death rates were in northern England. It didn’t help that much of the north had to endure tougher, tier 3 restrictions for months on end without, at least according to the region’s leaders, the financial help that might have eased the pain.

It was gendered. Though men seemed much likelier to die from Covid, it was women who were taking more of the strain. One survey found women reporting higher levels of anxiety over the virus than men, while later research produced the doubtless related finding that women were working harder and longer, now often doing their regular jobs from home as well as increased childcare. It concluded that women were 43% more likely than men to have increased their hours beyond the standard working week. The result: a rise in mental distress.

And it was generational. The old suffered most directly, of course, as it was the over-85s who were most vulnerable to the disease: more than nine in 10 UK deaths from Covid were among those over 65, with the average age of the dead over 80, according to the Office for National Statistics. But although the young paid less of a mortal price, their lives were badly shaken.

It might be the babies whose first months were deprived of the usual socialisation of seeing other babies. It could be the children who were home-schooled, the lucky ones treated to lessons in half-remembered maths from bleary-eyed parents coupled with the blessed relief of a Horrible Histories video, the less fortunate given next to no education from March to September so that a London School of Economics study in October warned of “permanent educational scarring” among a cohort of students who had lost time and teaching they would never get back.

Even among those less lastingly damaged, the cancellation of exams may have brought a fleeting surge of relief, but that soon gave way to a sense of unfinished business: they had been denied the closure of completion. Sixteen-year-olds had lost out on the post-exam summer that represents a coming of age: those sweet weeks of abandon and the first taste of adulthood. Eighteen-year-olds saw university places, and the dreams that went with them, slip through their fingers. Both were subject to the whims of an algorithm that, before its calculations were discarded – in yet another government cockup – looked with favour on children lucky enough to go to schools that had done well in the past, especially private ones. The coronavirus lens magnified a pattern of British life that predated the disease, a pattern indeed that predates us all: to those with much, more shall be given.

Those already at university found themselves either sent home or locked up, while graduates were pushed out into a job market that had rarely looked colder or more deserted. One recruiter reported a 60% fall in the first half of the year in advertised roles for those with a degree. The wider picture was not much better. Sixteen- to 24-year-olds accounted for almost 60% of the total fall in employment during the pandemic, with youth unemployment on course to hit 17% by the end of this year.

That’s partly because of the jobs that young people do: under-25s were much more likely to work in areas hit by social-distancing requirements, hospitality the most obvious. But it was also further confirmation of a trend in British life visible long before the coronavirus: saddled with student debt and thwarted by the shortage of affordable housing, the young are becoming the poor relations of their parents. Even inside companies, you could see it with awkward clarity: Zoom calls where older staff had a backdrop of a study in a spacious house, talking to younger colleagues perched on the end of a bed in a rented room.

Coronavirus was unforgiving like that, magnifying the blemishes on the skin of our society, showing up the deep lines that divide it. And given that it did that for regional, class, gender and age divisions, it was scarcely a surprise that it exposed racial inequality too. Among men in England and Wales, those of black African background had the highest Covid-related rate of death: 2.7 times higher than that of white males. Among women, the highest death rate was among women of black Caribbean background, almost twice that of white women.

There was no escaping it. Covid killed black and minority ethnic people in disproportionate numbers. Was there a physiological or even genetic explanation for that, perhaps rooted in a greater incidence among BAME communities of pre-existing conditions such as respiratory illness, heart disease and diabetes? The ONS put greater weight on matters of geography and income: where people lived and how much they earned. Experts pointed to the fact that black and Asian people were disproportionately likely to be in public-facing jobs – in hospitals and care homes, on buses and trains – or in multigenerational households, where they were at greater risk of being exposed to the virus.

Strictly speaking, it was a separate matter, unrelated to Covid, but it was grimly fitting that the other great upheaval of 2020 – the Black Lives Matter protests, where crowds gathered across the world, in city centres that had, until then, been empty, their faces covered by masks – had a slogan that carried an unintended echo of coronavirus and the way it kills. The phrase in question consisted of George Floyd’s last words, as he was beaten to death by Minneapolis police: I can’t breathe.

Of course, the racial injustice highlighted by the BLM movement had always been there but it’s just possible that a global crisis somehow provided the space in which people could at last look it in the eye. The first phase of the pandemic brought grief and loss to many hundreds of thousands across the world – a tally of death that would eventually rise beyond 1.5m – but in among the fear and the stress, it also imposed a rare and unfamiliar pause. An old refrain, resonant because of its futility, is “Stop the world, I want to get off.” Covid seemed to offer that opportunity: for a while, the world came to a stop.

It coincided with an uncommonly beautiful British spring. For those lucky enough to have outdoor space – a garden, a balcony, a patch of green – it felt like a chance to take a breath. People marvelled at the natural world they had previously ignored – plants or trees they had rushed past on their daily commute which, now that they took a daily walk around the neighbourhood instead, they saw, as if for the first time. A social media staple of the period was a photograph of a rare bird or unfamiliar animal spotted roaming deserted city streets, along with the caption: “Nature is healing.”

It wasn’t a wholly fatuous claim. City centres previously choked with traffic were now easier on the lungs. You’d look upward and see skies clear of aircraft: passenger air travel was down 90% year on year in April and down by 75% even in August, when lockdowns had eased and millions would normally be thinking of a holiday. A pair of environmental scientists found that the pandemic response had significantly improved air quality in different cities across the world, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, lessened water and noise pollution, and contributed towards a possible “restoration of the ecological system”. Of course, there was a downside: an increase in medical waste, including plastics used for PPE, gloves and, inevitably, masks.

Still, the year of the virus provided a glimpse of how things could be different. Those environmental researchers wondered if “the global response to Covid-19 also teaches us to work together to … save the Earth from the effects of global climate change”. Mike Clemence of the pollsters Ipsos reported that UK alertness to climate change – rising anyway since 2013 – increased by another five points this year. He picked up from his focus groups the view that 2020 might become a precedent, “a demonstration that large-scale social changes can be made pretty quickly – if people work with the government towards the same, simple goal”. It’s a hopeful thought. If we could show the same focus in facing down a persistent and gradual threat, the climate crisis, as we did in dealing with a sudden, immediate one, who knows what might be possible?

The lens of coronavirus showed up a great deal that was already happening in our world, but it also magnified much about ourselves and the way we live. Trends that predated the pandemic were accelerated. Working from home was already on the rise, but it went from being an exception to the rule. Many white-collar staff and professionals suspect they might never again return to the office or, if they do, it will be for only a day or two a week. The default expectation that work means a commute to sit in a big room, surrounded by others staring at the same computer screens you could all be staring at in your homes – that expectation has surely gone for ever. Every company that got through the pandemic in one piece made the case for the burial of the office: by managing without it, they proved its dispensability. Some organisations have already sold up or cancelled the lease they had on premises, concluding they won’t be needing them any more.

People were increasingly shopping online before 2020, and that trend too gathered pace: it’s estimated that the pandemic accelerated the shift from physical stores to digital shopping by about five years. You could see the evidence in the December collapse of Debenhams or the Arcadia group that included Topshop – and in the streets where once thriving shops were boarded up.

The combined effect of those two trends, their tempo turned to a gallop by Covid, could be a wholesale remoulding of British towns and cities, whose centres were shaped over centuries to host work and commerce. Both those activities were already making their steady migration into our homes, but the pandemic gave them an extra shove.

In 2020 we got a glimpse of a strange future: the high street deserted, while residential roads thronged with delivery drivers bringing to our door the things we used to go out to buy or consume with other people. Pubs were already closing at speed – 20 a week in 2019 – but the rolling waves of Covid restrictions, forcing pubs to close their doors for months at a time, proved too much even for many of those who had, until then, clung on.

The result was a secondary pandemic – of loneliness. The war against the virus deprived people of elemental human contact; the phrase “social distancing” became all too real. After just a week of lockdown, the proportion of Britons reporting a bout of loneliness rose from one in 10 to one in four. And that, in turn, fed a deep hunger for togetherness.

Quick Guide The five-day UK Christmas Covid bubble: how will it work?

Show

The government has announced that up to three households will be able to mix indoors and stay with each other overnight from 23 to 27 December under loosened coronavirus restrictions across the UK.

Can I eat out with my Christmas bubble?

No. In a blow to pubs and restaurants, and families who like to avoid the piles of washing-up, separate households in a Christmas bubble will not be able to meet up in hospitality venues. However, members of a Christmas bubble can meet at home, in places of worship and in outdoor public places including gardens. You can continue to meet people who are not in your Christmas bubble outside your home according to the rules in the tier you are staying in. If you are living in a tier 3 area in England, pubs ands restaurants will remain closed.

Is there a limit on the number of people who can meet up as part of a bubble?

There is no maximum size for a Christmas bubble, so you don’t need to worry if you and those you join with live in large households.

If I’m already in a bubble with another household, do we count as one household or two for the new Christmas rules?

Under the rules, a support bubble will count as one household when Christmas bubbles are being formed.

Can I join more than one Christmas bubble?

No, the bubbles have to be exclusive, and they cannot change over the five-day period – so pick your households carefully. This means that you can’t mix with two households on Christmas Day, and then a different two households on Boxing Day. However, children whose parents are separated will be able to move between two Christmas bubbles so they’re able to celebrate with both parents.

Do I need to socially distance from the people in my Christmas bubble?

Bubble members will not be required to social distance while they are together, so they can hug or kiss under the mistletoe. However, people are advised to exercise caution if there are vulnerable people involved in their bubble.

What about care home residents?

In England, some care home residents may be allowed to form a bubble with one other household, in agreement with the home and subject to individual risk assessments. In this case, social distancing should be maintained, with regular hand washing and ventilation to reduce risk. Care home residents should not form a three-household Christmas bubble at any point.

Can I travel to meet up with people in my Christmas bubble?

Individuals will be able to travel between coronavirus tiers and across the UK during the designated festive period (23 to 27 December). People will be able to travel to and from Northern Ireland for an extra day either side of that period, to allow for the extra time needed.

What if I live in a shared household?

In England, people living in shared households can split and join separate Christmas bubbles without breaking the three-household rule. So a group of, say, four young people living together would all be allowed to return home to their four separate families for Christmas and then come back to their shared home after the festive period.

It was apparent in those first weeks of spring, when the sun shone and there was a sudden and welcome outbreak of community spirit, incarnated by that weekly round of 8pm applause. You could taste a solidarity that we might have heard about from parents or grandparents but had only rarely experienced for ourselves. For a while, there was a feeling – however brief or illusory – that we really were all in it together. You were locked down, but so was your boss and so were the most famous people in the world – some of them posting excruciating video messages to prove it.

Perhaps that was why there was such a fierce reaction to Dominic Cummings and his violation of lockdown regulations, later justified with a comically unapologetic performance that centred on a claim to have driven to a Barnard Castle beauty spot solely to test his eyesight. It wasn’t just that Cummings had broken the rules; he had broken something we’d come to cherish: a sense of collective endeavour. He made those who had stayed at home and stayed away from their loved ones – even in their last, dying hours – feel like fools, suckers who had taken their leaders’ word at face value, not realising what the powerful had always known: that rules are made to be broken. Small wonder that public compliance after the Cummings affair never again reached the level it had achieved before. Scholars called it the Cummings effect.

The bitterness of that betrayal will fade, not least because by year’s end Cummings had gone. But how much of the sentiment that made it sting – that sense of shared destiny and shared effort – will endure? Britons will surely remember the gratitude they felt for the nurses, doctors and care workers who protected them when coronavirus was still such a mysterious menace, when we didn’t know how – or how easily – we might catch it, or how deadly it could be. But the extension of that admiration for other key workers who were keeping the country going, perhaps that was more fragile. That the chancellor felt able to impose a public sector pay freeze in November on all but NHS and care staff suggested he, at least, had drawn that conclusion.

Even so, the pandemic did allow us to learn again what we value most. Along with healthcare workers, scientists were the year’s heroes – a reminder that, when it comes to life and death, and despite Michael Gove’s notorious 2016 declaration, the country had not had enough of experts. On the contrary, we couldn’t get enough of them – urging them, begging them, to come up with a vaccine which, incredibly, they did, and with unprecedented speed.

We learned who we are by what we missed. Life without even the possibility of a trip to the pub; a night of laughter at the theatre; tears at the cinema or the thrill of live music; an afternoon shouting yourself hoarse at the football; a quick chat over a drink or a long meal with friends; a few hours with your parents or your children; or a simple, wordless hug – that kind of life was hollow and hard. We longed to know those pleasures once more.

The pandemic took away so many lives, but it also reminded us what life is for: the simple joy of being with other people, close enough to touch and be touched. Like a magnifying glass placed over each one of us, the virus revealed what is our greatest weakness but also our most precious strength: our need for each other.

Throughout 2020, Guardian journalists have worked round-the-clock to dig out the truth about the pandemic. Because good journalism can help save lives. Support independent media. Support the Guardian.

Read more about how Covid-19 changed everything in a special supplement in Saturday’s Guardian