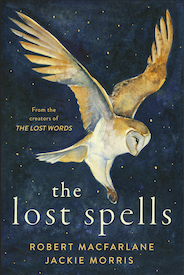

In a perfect world I would have had this conversation with Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris in a cozy pub in the English countryside, sat by the fire with a properly sized pint of stout, trying and repeatedly failing to stay on topic (in this case, the topic being their latest collaboration). Instead, we corresponded about The Lost Spells—a luminously illustrated compendium of poetic “spells” conjuring the natural world—via email.

*

Jonny Diamond: Rob, there’s something of the radiant mischief of Gerard Manley Hopkins (verbs getting noun’ed, nouns getting verb’ed) in these poems, a call-back to his “sprung” rhythm. Who do you think of as your poetic forebearers?

Robert Macfarlane: Ha! Thank you. “Radiant mischief”; that’s just right for GMH, and verbing nouns and nouning verbs is definitely my jam. So Hopkins, undoubtedly; “The Windhover,” where the miraculously hovering kestrel suddenly folds and dives “as a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend,” and the wild rumpus of “That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire…” Also Seamus Heaney, whose “strong gauze of sound” (“Death of a Naturalist”) wove round my ears from early in my reading life.

And all of the kennings in The Lost Spells—my love in this book and its big sister The Lost Words, of compounding words together with hyphens to make new hybrids with fresh energy (the wheeling swifts in the Swifts Spell as “havoc-wreakers, thrill-seekers… gung-ho joy-bringers, spring-harbingers”)—well they come from Old English poems like “The Seafarer” and “Beowulf,” which make such powerful play with kennings (the sea as the “hwael-weg,” “the whale’s way”; wind as the “tree-breaker”).

But also—as alluded to above—I’ve been influenced by incantations like those of Maurice Sendak in Where the Wild Things Are, or writers such as Alan Garner, Susan Cooper and Ursula Le Guin, who are so deeply involved with the oral origins of writing, and whose work celebrates the power of the uttered word. “When the dark comes rising / Six shall turn it back / Three from the circle / And three from the track…” Who could forget *that* spell-chant, once read, from Cooper’s The Dark is Rising? Not I…

JD: Song, incantation, conjuring… This is a book made to be read aloud. In your collaborations, though, did you do much reading aloud to each other? And was there much workshopping to the children in your lives?

RM: Jackie may, I think, have things to say about this! Jackie is the first reader of any spell after me, and I always send her first versions by email or message, prefaced with an order: “To be read aloud…” During the writing of The Lost Spells, I became even more demanding, as Jackie will be better placed to describe…

I’d add that I would often catch or hear a single line of a spell in my mind, and then deliberately not write it down, to see if it stayed within earshot or earsight, as it were. If it did—like the first line of the Beech spell, “Beech gives wind speech”; or of the Thrift spell, “Thrift thrives where most life fails, falls, is cast adrift…”—then I generally knew that if I pulled on that thread, a spell would ravel itself into being.

Jackie Morris: Yes, speaking aloud.

I have worked in picture books for 30 years now. Usually when they are read they are spoken aloud. Picture books are more than “just a book,” they are a place shared by adults and children. I learned the craft of it while reading to my own children when they were young. At one point I did ask my accountant, given the amount of learning and research I did while bringing up my children, could they be considered to be tax deductible. Sadly, no. But seriously, when writing these books the best idea is to speak aloud each phrase to hear how it tastes in the mouth and the mind.

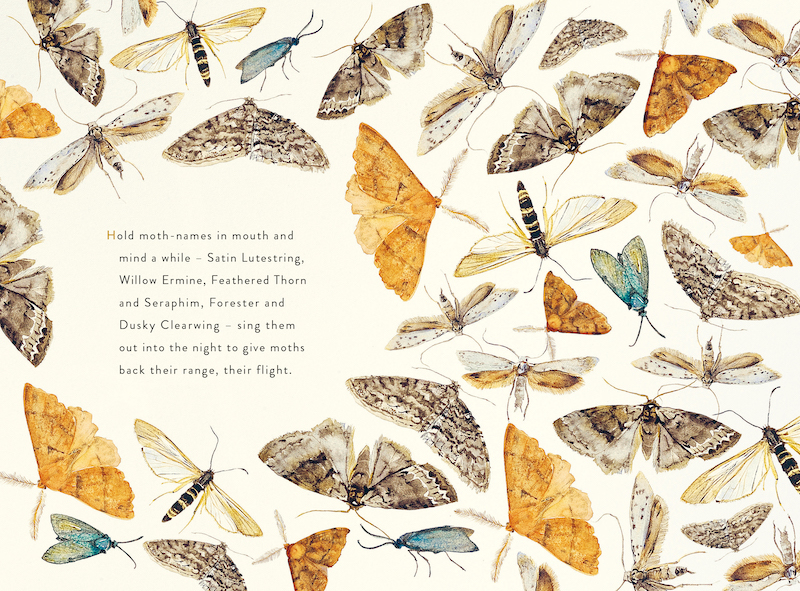

I’m hoping children will remind their parents of how they felt when they were young, about the world and how utterly filled with wild magic and wonder it is.This is something Robert caught on to with some enthusiasm, though after a while he would say, “Here is Curlew. Print off, but don’t read. Instead, take it to a liminal place, dusk or dawn, a beach, and estuary. Then read. If it flies there it should be right.” Moth was difficult. It arrived in the morning but the idea was to wait until disk. Just enough light to read by and speak it, quietly into the air, where bats were crisscrossing the sky with late birds, and moths taking the sky from the butterflies, drawing in the night.

All images copyright Jackie Morris.

All images copyright Jackie Morris.

Each word needs to pleach like a beech, with each word, so that each sings with the space between to the other. Also, try taking The Lost Words Otter Spell to a river bank and speak it quietly at dusk at dawn. You will find magic.

RM: My daughter Lily, now 17, has been one of the earliest listeners to the spells of this book and one of the first to see Jackie’s art. Her wise eyes and ears have been important to us. And my youngest, Will, now 7, has been a fine foil for it all too, not least as he rightly thinks my words are basically a distraction from the main show, which is Jackie’s dazzling art. He worships Jackie, and is always pestering me to set up WhatsApp calls with her. He crawls into The Lost Words, a book that for a few years was big enough for him to enter, as one might a landscape.

JM: My children are older because I am old (they are 26 and almost 28 and away from home)… I tend to read the spells to the birds. At times when I was working on The Lost Spells my daughter was home. She walked in to the studio one day—there’s a sign on the door that states: “Do Not Disturb Unless House is On Fire!”—but my children ignore both me and it. I was painting a piece for Barn Owl and there was an owl’s foot, a wren’s wing and an owl’s feather on my drawing board. “You are seriously weird,” she said, and walked out.

I really valued Lily’s comments on both of the books and love how Will has been drawn in to write and paint his own spells.

JD: There is a feeling throughout this book, the way text flows through the image, of nature being smuggled into the home, which seems pretty important as millions upon millions of us are so much more housebound than ever before. Do you think The Lost Spells might be read differently during a pandemic as opposed to what I’ll call the “before times”?

RM: We finished the Silver Birch Spell just as the viral storm was beginning to howl across Europe and America. It’s a “lullaby” about shelter from harm, about rising dark, about nature’s power to protect and console. “Round and round the dangers prowl / —wolves and monsters, worries, witches— / but the birches stand like churches / as the dark around them surges…” Many of us heard with new ears and saw with new eyes during the first spring of the pandemic in particular, when the traffic stopped: London as a capital city that was also a wildwood, with a deafening dawn chorus being belted out by the birds from its nearly nine million trees; the vital presence of spaces of nearby greenness (nature reserves, city parks), when social life became confined (or expanded, we might say) to outdoor settings only.

JM: When The Lost Words was published camera crews went into schools to see if children knew the words. I constantly said, don’t go into schools, go into offices, factories. Ask grown ups. Many of them don’t know these words. Many of them walk through cities, heads in phones, don’t see the wild life around them. Our children are educating us because we have lost our way. Children have a natural sense of justice. They question things we take for granted. Things like why people have to sleep on streets while houses stand empty. Like why a tree has to be cut down to make a car park. Our children are holding us to account. I’m hoping they will be able to use The Lost Words and The Lost Spells to remind their parents of how they felt when they were young, about the world and how utterly filled with wild magic and wonder it is.

JD: When I think of illustrated books, I think of the art following the text (that might be my bias as a writer). What was the order of ideas here… Jackie, were there creatures or trees that you particularly wanted to see included, that you drew for Rob to write toward?

RM: I’ll just say here that, as the writer, I found Jackie’s art often vital to the rhythm a spell took across its length; how space and thought were shared between stanzas, and how they interacted with the drama and beauty of her art. Among other things, Jackie has an extraordinary understanding of how space—including the blank page—works, and how stories gain their drama through the grammar of the turned page, or the eye’s movement around a panel. I’ve learned so much from her in this way and others. The Lost Spells, unlike The Lost Words, tells its stories and sings its songs often across multiple pages. The Silver Birch Spell is less than 200 words long, but stretches over 26 pages; Jackie’s work turns a shortish poem into a mini-novella.

JM: You can “decorate” a book with images, or you can “illustrate.” The strength of words and images working together is that you can make the words more accessible to so many more people. You can tell stories through images and words hand in hand. Sometimes when an idea is growing for how to sit a spell in the mind’s eye I have to show, not tell, drawing sketches to share with Robert. The strength of this book is in the space between the word and the image, a place inhabited by the reader. The language is rich, in both books. No talking down, no infantilization. And we are constantly told how reluctant readers love the book. We are shown such astonishingly rich work inspired by image and word. And, as I am fond of saying, words are made from 26 letters of an alphabet. These letters are images that conjure sounds in the mind’s ear. So, at the end of the day, it is all about images.

Many of us heard with new ears and saw with new eyes during the first spring of the pandemic in particular, when the traffic stopped.JD: Rob, verse forms seem so well matched to the animals they describe (the conjuring fox, the prose-poem moth, the staccato jackdaw, the interjecting jay…). How intentional was that, and what was the hardest voice to find for any of these?

RM: Do you know, I hadn’t even seen that the Jay spell is characterized by interjection: “Jay, Jay, plant me an acorn / I will plant you a thousand acorns…” D’oh! Thank you. You’ve changed my understanding of it as a jayish spell. I am a big fan of the corvidae generally, and so we have the Jackdaw Spell and the Jay Spell here, and a Raven Spell and a Magpie Spell (the “Magpie Manifesto”; “interrupt, interject, intervene!”) in The Lost Words. All are shouty, convivial, chatty, chattery, confident spells, just like the birds they name. Here in the UK I laid down a “Jackdaw challenge” to children and schools; could they remember that 57-line spell by heart, and perform it from memory? It’s caught on fast, and we’ve already seen whole classes on their feet chanting it out; Jackdaw rap-battles between kids; “flock” recitals where one person does one stanza and one another… and the national “Poetry By Heart” initiative has added it to their project.

As with The Lost Words, too, lots of the spells in The Lost Spells are already being set to music: the great Cosmo Sheldrake, whose music has among other things been covered by the Pentatonix, has done a witty, witchy setting of the Beech Spell.

JM: Learning the spells by heart is a wonderful thing to do. They become part of the geography of your mind and imagination.

JD: Jackie, is that the same fox, among the silver birch, that we met at the start?

JM: Yes. And this has to do with not working a book page by page but keeping in mind the whole of it as each part progresses. How the pages turn. And the blackbird is Robert, singing at the dusk and the dawn. The same fox. The same blackbird.

JD: Further to the importance of naming the natural world, was there always going to be a glossary? (I love glossaries.)

RM: Mmmm… I love glossaries too. So much so that I wrote a book of and about them, Landmarks. Here in The Lost Spells the glossary is dedicated to the work of good naming as an act of both honoring and loving the beings with which we share this world. But it’s also designed to make that transition from page to place, word to world, in urging its readers to take the book into field and woodland, park and garden, and “seek, find, speak” the names of the nearby-nature. The extent of the glossary is also testimony to the sheer range of Jackie’s knowledge and art; though there are 21 species which are the main “named” subjects of the spells, from Barn Owl and Curlew to Swallow and Woodpecker, there are 64 species included in Jackie’s paintings, so they are what make up the glossary as image, common name and scientific name. The Lost Spells is, among other things, a praise-song to diversity.

JM: This whole book was worked in a very organic way. It began as twelve spells, elbowing its way in past a bigger book that Robert and I were and now are working on, The Book of Birds. Twelve became twenty, which felt right, it matched The Lost Words. I’d seen a way to separate out the acrostics, running over pages, some turned swiftly, some slower. But then about 3/4 of the way through I realized that I’d done what I always do and wriggled into the images many other species. And the idea of the glossary came.

The acrostics and spells were so strong. I needed my paintings to be like visual poems, to stand beside such words. And the glossary would add a “puzzle” element. You get to the end and you see more, and you can go back and find each creature. And Rob wrote the beautiful intro to it. And meanwhile, having tried and failed to find the words for Silver Birch the words began to settle, as he had drawn back from the spell and the Birches grew towards him. So, we had 21 spells. And a glossary. And that seemed just about right.

I love the glossary poster that accompanies the book. This, like the books, was designed by Alison O’Toole. The importance of a brilliant designer in the look of a book can never be exaggerated. She reads each word and understands about space and balance and how to really make a book into an object of desire.

So, even when the book was finished it still wasn’t. The design came back and Silver Birch was worked over four spreads. It’s such a tranquil spell for sleeping it seemed cramped. I asked Robert and Hamish Hamilton, Hermione Thompson and Simon Prosser, if I could rework those last few pages. I hoped there was time as Alison was still working on organizing the chaotic glossary. It needed space to move, to breathe. And they said yes. And so the main body of the book closes with that journey into the safety of the birch trees and out to a new dawn. And that is how books should be. Allowed to evolve into the best they can be.

For now.

___________________________________

The Lost Spells is available from House of Anansi press.