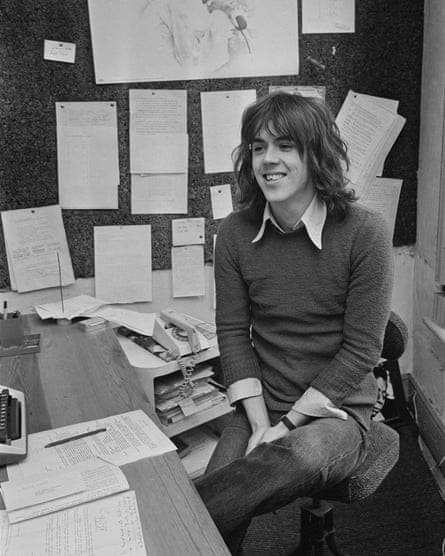

Plenty of young people had wild ideas in the summer of 1968, but Tony Elliott, who has died aged 73 after a long illness, had a great one. It was simple and not entirely original, but it was instantly different from the profusion of alternative publications bursting out of many basements and bedrooms in those years.

In his mother’s London flat that August, Elliott began compiling a folded news sheet for young Londoners – in a world decades away from the internet – about what was on and where to go in a city blossoming with new cultural and political ideas that the mainstream press mostly ignored. A 1959 Dave Brubeck jazz album gave Elliott his title – Time Out – and thus did the first A5-sized edition appear, covering 12 August to 2 September 1968. By late September, the magazine had grown to a stapled booklet published fortnightly. From the early 1970s it was essential reading about anything from fringe theatre to the Troops Out movement, squatters’ rights, or where to buy a waterbed. Three decades later, it would be a global publishing phenomenon from Berlin to Barcelona, São Paulo to Seoul.

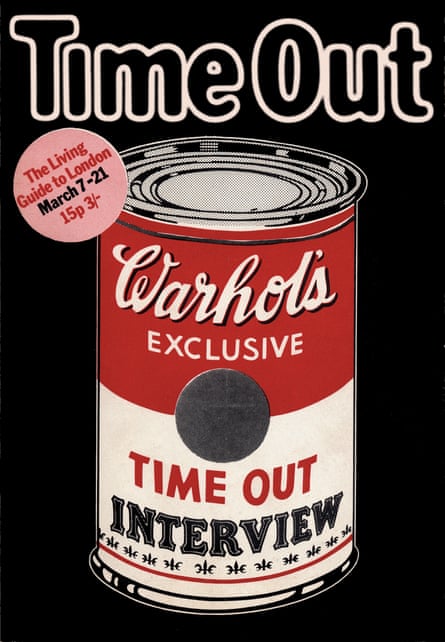

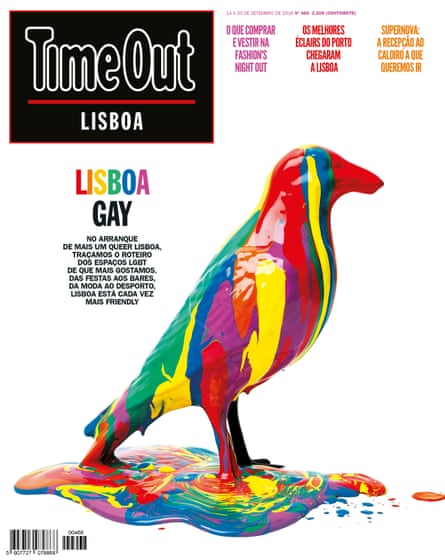

During the ensuing half century much of the radicalism of Time Out’s first decade would be scattered to the winds, but Elliott’s mantra of “the information behind the information” drove the rise of a global media brand. Time Out New York, in 1995, was followed by more than three dozen editions in cities around the world, a clutch of travel guides, digital platforms, magazines and a chain of Time Out markets.

Elliott had spotted that in the cultural ferment of the late 60s magazines such as International Times (IT) were often creatively brilliant, but short on hard information. In the 90s, the IT veteran Dave Robins recalled in the pages of Underground: The London Alternative Press 1966-74 how the paper had spurned listings expansion when Elliott and his co-founder (and DJ-to-be) Bob Harris dropped by to suggest it.

Elliott realised, Robins said, “that listings were what people had liked about IT, not the long and boring articles about sex”. Mainstream listings magazines of the time looked dated, focused on tourism and “adult” entertainment, but Time Out was the one with its finger right on 60s London’s racing pulse.

In late 1970 Elliott recruited the designer Pearce Marchbank, and the next year Time Out shifted permanently to an A4 format, published weekly. Extensive news and arts stories began accompanying the listings, with Elliott – despite Mick Jagger’s alleged complaint that the campaigning news section was the picket line you had to cross to get to the listings – firmly backing his magazine’s voice, even if it brought police investigations or indignant litigants. As his editors regularly noticed, Elliott’s own antennae were sharp, whether anticipating the rise of David Bowie or an unlikely hit film such as Saturday Night Fever.

By the end of the 70s, Time Out was selling more than 40,000 copies a week, yet it retained its radical edge, in both investigative journalism and cultural politics. But by then a polarised atmosphere was growing on the magazine. In the early days, people such as the socialist feminist historian Sheila Rowbotham were contributing to Meet the Fuzz, the then agitprop section. By the mid-70s the vast majority of the staff were on equal pay – but in 1981 Elliott and his management called time on a structure they had come to regard as uncompetitive, and the resulting dispute and strike lasted from February until September, during the fateful time of the Brixton riots.

The impasse ended in a painful split, with around two-thirds of the 60-plus staff (the present writers included) founding a rival magazine, City Limits, run on equal pay. By that October, both papers were on the streets, leaving Elliott to rebuild his empire on his own terms. After a rocky start, the cooperatively run City Limits consolidated its audience, repaid its Greater London council startup loan and provided an alternative voice to Time Out for a decade, until its closure in 1991.

During those years, Elliott won a personal battle to give up nicotine and alcohol, and Time Out fought a successful legal one to end the Radio Times’ and TV Times’ monopoly over publishing television listings.

After the strike, contributors to Time Out included the writer Tariq Ali, and there was still a strong newsroom, but the consumerism it had depended on moved closer to centre stage. The arrival of Time Out New York in 1995 was a key moment in the evolution of Elliott’s dream. Some New Yorkers mocked the interloper as suitable only for the “bridge and tunnel crowd” – those who only came into Manhattan at weekends – and the city’s original underground paper, the Village Voice, was still influential.

But just as Robins had witness- ed Time Out’s displacement of IT in the 70s, so the Voice’s readership succumbed to the same brand in the 21st century. Time Out became increasingly good at the whole online leisure-consuming package, from discriminating guidance to booking tickets and restaurant reservations.

Despite a brush with prostate cancer in 2005, Elliott kept a firm hand on the tiller that wavered only with the growing impact of his online competitors and the 2008 recession, which forced him finally to split his 100% ownership with outside backers two years later. But he tirelessly supported charitable causes, such as the rehabilitation of London’s Roundhouse arts centre, the NGO Human Rights Watch, and a raft of rising artists’ projects. He also lent his experience as an adviser or director to organisations from the British Film Institute to the Photographers’ Gallery, Somerset House Trust, Film London and the Manchester international festival.

In 2017 he was appointed CBE and received an Outstanding Contribution accolade at the British Media awards. The building of a Time Out archive and the magazine’s 50th anniversary were absorbing his energies by the time he arrived, visibly apparently unscathed, at his 70s.

Born in Reading, Berkshire, Tony was the son of Alan Elliott, a marketing executive, and Dr Katherine Elliott, assistant medical director of the CIBA Foundation. He had two sisters, Veronica and Rose. Tony was educated at Stowe school in Buckinghamshire, Westminster Further Education College and at Keele University, Staffordshire, where he studied French and history.

However, he was renowned at Keele for spending almost as much time commuting to London in a battered VW Beetle to hang out in underground arts haunts as he did at the university. In 1967-68, Elliott had brought the celeb interview and a small London readership to Keele’s arts magazine, Unit – with features on Jimi Hendrix, RD Laing, Yoko Ono and Joseph Losey – before the idea for Time Out led to him dropping out. It was in that period that Elliott met the Australian Richard Neville, one of the three editors of the most famous underground magazine, Oz. “I never forgot his words,” said Elliott. “He said, ‘If you get this into WH Smith, put your name down for a Rolls-Royce, immediately.’”

His loyalty to old relation- ships, but fierce defence of his independence in all areas of life, made him an inspiring friend whose warmth was sometimes camouflaged by his shyness, and a formidable opponent if he felt his autonomy was being invaded – as was evidenced in the bitterness of the 1981 dispute. Long after that dust had settled and conversation had resumed, the three of us would meet for dinner occasionally – he was never less than solicitous about our lives, and as enthusiastic about Time Out’s affairs as he had ever been.

Elliott brought together in his offices countless talented observers of London’s vivid creativity and changing character, many of whom would build careers and form lifetime friendships through it. In Time Out’s best years he had contributed to doing the same for communities of many kinds all over the world.

In 1976 he married Janet Street Porter; they divorced two years later. In 1989 he married Janey (Jane) Coke, and she survives him, along with their three sons, Rufus, Bruce, and Lawrence, and by his sister Rose.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion