Since the mid-19th century, the city of Leeds has proudly greeted visitors from the south with some of the most elegant towers in the land. As the train snakes its way into the city centre, a trio of fine brick chimneys is revealed at a bend in the river, each styled after a different Italian renaissance tower. One mimics Giotto’s Campanile in Florence, another echoes the Torre dei Lamberti in Verona, while a third recalls a Tuscan towerhouse in San Gimignano. It was the ornate fantasy of Victorian industrialist Colonel Thomas Harding, who hired architect William Bakewell to conjure the most beautiful ventilation shafts that a Yorkshire pin factory had ever seen.

In recent years, this sophisticated scene has been overshadowed by towers of a different kind. First came the ranks of tacky waterside apartments, each topped with a jaunty curved roof, adding a touch of service station chic. Then came Bridgewater Place, the tallest building in Yorkshire, which squats like a bulky grey Dalek on the skyline. Its malevolence extends beyond its looks alone: the wind created by this “killer tower” at street level swept a lorry on to the pavement, crushing a man to death, and has injured others.

Now all of this is to be trumped by the most audacious shaft that God’s Own Country has ever seen. Rising to 46 storeys, Two Springwell Gardens is planned to be the new tallest building in Yorkshire, a 142-metre glass monolith rising from the industrial sheds of Holbeck. In a Ballardian flourish, it promises to house glamorous “sky gardens”, where spiral staircases wind their way through luscious hanging plants. Cocooned inside these sealed vertical patios, residents will experience “an enhanced sense of community” as they look down on the surrounding landscape of builders’ depots and tyre shops.

The building “has a bold visual identity, thanks to a distinctive sail-like facade”, says Antony Georgallis, director of local developer Citylife, which was founded five years ago and has yet to realise a completed building. “By being brave with our design, if planning is granted, we will contribute towards a new skyline for the city.”

Sadly, for the future residents of the high-rise, it seems like both developer and architect, Nick Brown, have been so focused on the skyline that they forgot to think enough about the inside. When the building’s floor plans were first revealed on social media, architects and planners were aghast. “Inhumane, incompetent, inexcusable,” was the verdict of housing expert Claire Bennie, former development director of the Peabody housing association. “Abomination!” added another.

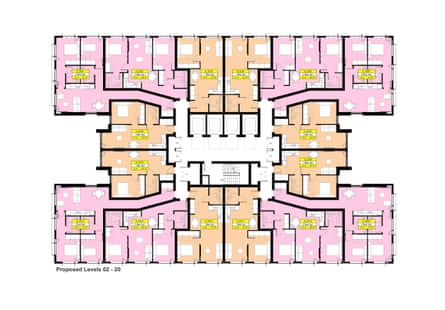

Cramming 16 apartments per floor around a single access core, with just one escape staircase, the plan looks like some contorted Space Invaders monster with a fire-hazard death-wish. Some flats have been so shoehorned into the corners that they necessitate having 12-metre-long windowless corridors to reach them. The mirrored pairs of crooked passages extend from the lift core like great fallopian tubes, pregnant with the promise of an endless journey from the front door to the living room through a one-metre wide tunnel. Some flats seem to be one-third corridor. As one commenter put it: “The apartments are basically just corridors of varying width, from depressing to furniture-containing.” The “affordable” flats, meanwhile, have been tucked into the armpits of the H-shaped plan, recessed in the shadow of their neighbours.

Architect Nick Brown is sanguine: “Our approach is to work to the technical regulations and take it to the limit of what is acceptable within those boundaries,” he says. He also thinks the long windowless corridors could be a positive feature. “Residents could actually turn those corridors into a gallery or something,” he says. “It’s part of the arrival sequence, building up to the amazing views you’ll get when you reach the apartment.”

The Leeds Civic Trust is not convinced. “This is a scheme that’s trying to do far too much with the space available,” says the trust’s director, Martin Hamilton. “Some of the flats will get very little natural light, and there’s no private amenity space for the residents. It looks like a pokey arrangement for coming and going, and the single escape stair is a real safety concern for a building of this height.”

Brown responds: ‘We’ve been working with fire consultants and we are satisfied that it is safe and it meets the requirements. Every apartment is sprinklered, and the core is the required size for the building, with compartmentalisation and two-hour fire protection. We are aware of the sensitivities of tall buildings and we continue to challenge ourselves.’

The scheme would fail to meet the London housing standards on multiple fronts. Sixteen flats is twice the number permitted to be accessed from a single core for safety reasons, while daylight and natural ventilation are also required for communal corridors. The lack of personal outdoor space for each flat wouldn’t meet the standard either. “We originally had balconies, connected by a green wall,” says Brown. “But we had to get rid of the green wall due to fire regulations. Then the balconies became too exposed and windy to use.” He says residents will be able to use the courtyard of their neighbouring scheme, One Springwell Gardens, an (unbuilt) lower-rise block that received planning permission in 2017. The civic trust has pointed out that the tower would cast this space, and the building itself, in shadow for much of the day.

While One Springwell proposed to include 5% affordable housing, Brown says they couldn’t find an interested housing association, so paid the council a commuted sum instead. He says Two Springwell meets the council’s updated requirement for 7% affordable housing, but again there is no guarantee it will be provided on site. These luxury residential havens will be a stark arrival to what is one of the most deprived wards in the country. They are located in the small grid of streets that was designated the UK’s first managed red light district in 2016 – an initiative that sadly doesn’t seem to have improved prospects for either the women or the area. As one local business owner told the Guardian last year: “Murder, serious assault and rapes have all taken place on the zone. We see condoms and needles all over the place, and even human faeces.”

For those who have been watching the Leeds development scene over the years, this tower may be the tallest, but it represents a new low. “It’s appalling,” says architectural historian Ken Powell, who has been involved with Leeds since the 1970s, working with Save Britain’s Heritage and castigating the so-called “Leeds Look” – a kind of joyless postmodernism featuring red bricks, grey slate roofs – that emerged in the 1980s and 90s. “It’s just another large object stuck in space, without any concern for its context. The city needs some kind of vision, which they simply do not have. These tall buildings have sprung up in a very unplanned way, just dumped along the fringes of the city centre in a meaningless jumble.”

Retired town planner Adrian Jones, author of Towns In Britain and popular blog Jones the Planner, agrees. “The scale of it seems mad,” he says. “They’re proposing to plonk 600 units in a desert. This would represent around 20% of Leeds’s total housing supply needs for a year – in a location with no sandwich shop, no newsagent, no pub. It’s an industrial area, cut off from the city centre by roads and railway lines. This tower has just come out of nowhere, with no real plan.”

Like Powell, he sees it as a symptom of the lack of an overarching vision for the city. “Leeds is really two cities,” he says. “It’s got the really good stuff in the centre – very urban and quite cosmopolitan – then this no man’s land pretty much all the way around it, that’s been messed up by highways and demolitions and the loss of industry. Then all this new stuff is being scattered around in a random fashion. When you’re there, it feels like there’s no urban structure.”

Two Springwell Gardens is the latest of a rash of tall buildings in the city, many of which have sprung up around the Leeds Arena to the north, forming a notional “cluster”. “From a distance, it looks quite impressive now,” says Jones. “Then when you actually reach them, the quality is terrible.”

The chief offender of the bunch is the Opal 3 Tower, a 25-storey cliff face of student flats punctured by tiny square windows and topped with an inexplicable red triangular crown, like some bloated rooster. The work of Derby-based Morrison Design, it was the tallest building in the area until the arrival of the Sky Plaza tower, a 37-storey silo of 557 student flats designed by Leeds stalwarts Carey Jones. It was clad, until recently, in the same kind of flammable aluminium composite panels that clothed Grenfell Tower. There are several more similar towers on the way nearby, including another pair of tombstones for Unite, rising to 27 storeys, and Altus House, a lacklustre 38-storey doppelganger of its neighbours. Sharing the same palette of whitish cladding, this north end of Leeds is starting to look like a depot of discarded fridges.

“There is a recent tendency for the council to say, ‘Well, we’ve approved something that looks like this in this area, so we want something similar,’” says Hamilton. “Sure, it may be policy-compliant, but something that offers a contrast would be more welcome. Our concern is that you end up with a rather monotonous blancmange, rather than something more interesting.”

A spokesperson for Leeds City Council said: “The Council determines all planning applications on their individual merits, including applications for ‘tall buildings’, in accordance with national and local planning policy guidance and legislation.”

Like many cities, Leeds has always had a fairly permissive approach to tall buildings, sitting back and seeing what developers offer, rather than proactively masterplanning in advance. Tower locations seem to be justified after the event, any notional “strategy” playing catch-up with the market. The council issued a new draft Tall Buildings Design Guide for consultation last year, but it still lacks teeth, full of vague principles that seem intentionally open to interpretation. The council says responses to the consultation are still being considered to help prepare any second future version, prior to any formal adoption. For developers, the flexibility is a boon.

“The planning system in Leeds tends to be reactive,” says Brown, who is also a co-director of the Citylife development company. “For us, that leaves the window open to propose things and come forward with our own thoughts on what the skyline should be.” So is this city-fringe area of warehouses, woodyards and kerb-crawlers really the right place for Yorkshire’s tallest tower?

“Normally, the tallest building arrives last, as the crowning glory of a regenerated area,” says Brown. “We’re doing it back to front. It’s a real stake in the ground for Holbeck.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion