One of the great things about boxing is how accessible the fighters are. One of the worst things about boxing is how accessible the fighters are. It can leave them open to opportunists, chancers and even slow-witted family members with good intentions but no idea about the business or it can leave them open to opportunists, chancers and slow-witted family members with plenty of business acumen but unwholesome intentions.

For years fighters have been preyed upon, abused ripped off. They’ve welcomed people into their inner circles who had no business being there while having everything to gain and nothing lose.

Some fighters are just kind to a fault.

A couple of weeks ago in a column here I referred to a trip to Dallas to report on Manny Pacquiao-Joshua Clottey in 2010. While I was in the area, I decided to look for former Muhammad Ali and Ezzard Charles opponent Donnie Fleeman. Well, Donnie wasn’t in when I first tried so without a number to call but with an address in my notepad I decided to visit former world welterweight champion Curtis Cokes.

I pulled up outside a modest looking place in the suburbs, rang the doorbell and instantly recognised the man who answered because I’d seen Curtis at the International Boxing Hall of Fame when he was inducted in 2003 alongside Mike McCallum, George Foreman, Niccolino Locche and Budd Schulberg. It was quite a class.

“I enjoyed every moment of it,” Cokes said of his career when he was enshrined back then. “Boxing is a real fun sport to be involved in.”

Seven years on, at his home, Cokes welcomed me in like an old friend even though we’d never met. Would any of the guys at Cooperstown have done that without a second glance? Would a retired Premier League player have done that? Or would I have had to run the gauntlet of agents and managers and anyone in a queue wanting to get their cut.

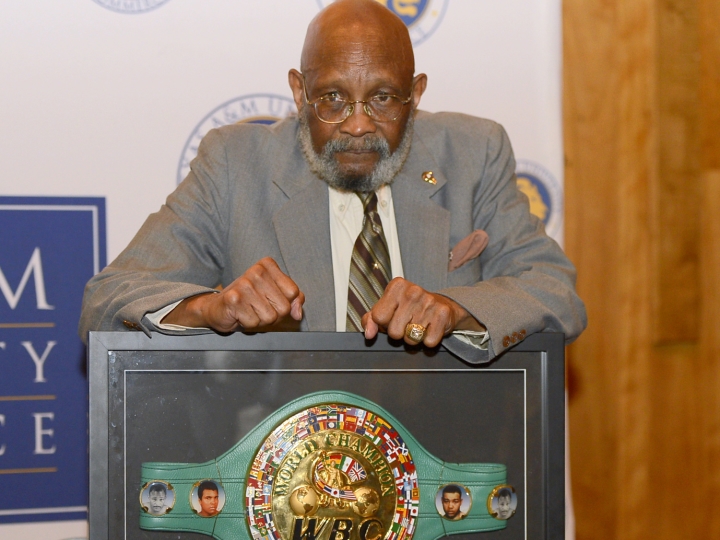

Curtis and I sat at his dining table and reflected on his career. High in the corner of his front room was a glass cabinet and it contained something none of the houses in the cul de sac had, a green and gold WBC championship belt. It was pristine.

Cokes was 72 at the time and still trained fighters. He was working with Kirk Johnson and spoke incredibly fondly and with a huge amount of pride and warmth when I brought up his former charge Ike Ibeabuchi, who had subsequently flown spectacularly off the rails when he was 20-0 before landing himself in prison.

“Ike was one of my favourites,” Cokes sighed happily. “His mother brought him to me and I put him in the Golden Gloves and he won everything until the nationals. He was a fine student, learned real fast and he wanted you to teach him something new every day. If he was still fighting he could be champion of the world now.”

It wasn’t to be for the tormented Ike but it had been for the wonderful Cokes who had known all about struggle having not been allowed to box in the Golden Gloves because they weren’t integrated at the time. Because of that, he couldn’t make his way to the Olympics.

“It left a bad taste in my mouth that’s still there today,” without managing to sound at all salty.

Nothing could snap his mood and he seemingly enjoyed being able to reminisce with this stranger from England about his fights with Luis Rodriguez, Jose Napoles, Joe Miceli, Stan Harrington, ‘Gypsy’ Joe Harris and Manny Gonzalez before a detached retina spelt the end of his career.

He didn’t want to walk but he knew it was time.

“You should make that decision yourself,” he advised. “Most fighters don’t want to give up the glory. A lot of fighters don’t find anything else to do. I chose boxing, boxing didn’t choose me, so I could do things other than box.”

Cokes had worked at a meat-packing company until he won the title. He didn’t go back, but he ran the tyre department in a car dealership in retirement before boxing lured him back and he could impart his wisdom on the likes of Reggie Johnson and Quincy Taylor.

He retired with a 62-14-4 (30) record. He’d been married three times (“knocked out all three times”) but loved his six children and was living happily with a brother and sister in a house he bought for his mother in 1967.

It was a pleasant but unspectacular home lived in by a man who’d done some spectacular things. Curtis Cokes was universally liked in the sport and that’s a hard enough an accomplishment in itself. I could see why everyone had time for him. He’d welcomed me in and indulged me, talking about the good days and the hard fights.

Is there another sport that makes its major players so accessible but so vulnerable at the same time?

A few years later, around the time of another big fight at the Cowboys Stadium in Arlington, an employee at Sky Sports asked me to put them in touch with Curtis. When they tried the house, they were told that he was no longer well enough to do interviews.

Curtis died last week, May 29, aged 82. He was a lovely man and I will cherish our time together.

As we shook hands and I got back into my car to leave, Curtis came by the window and smiled: “Boxing has been my life.”

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (1)