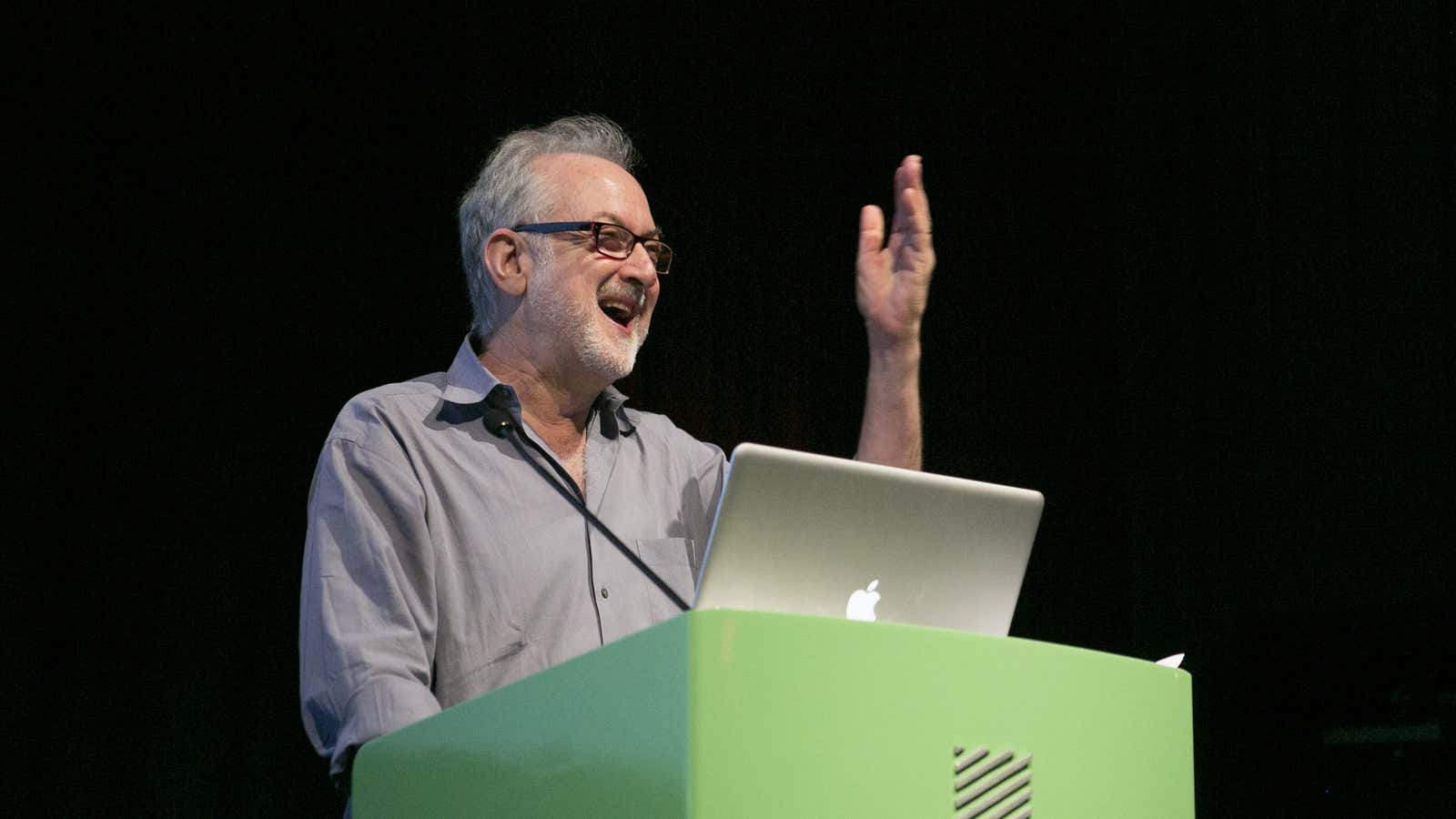

The architecture industry lost a pillar this week. Michael Sorkin, legendary architect, urbanist, and critic died of complications from Covid-19 in New York City on March 26, as his studio confirmed. He was 71 years old.

In a tribute published in the American Institute of Architects’s journal, architect Michael Murphy noted that Sorkin, who had been going through rounds of cancer treatment, was part of the demographic of older adults who were most vulnerable to the novel coronavirus. “It is only too clear that we have lost an oracle and a soothsayer,” Murphy wrote. “Michael Sorkin was that elder, for all of us in architecture.

Sorkin’s legacy is firmly rooted in designing sustainable cities—a pursuit he championed long before it became fashionable. “I firmly believe that reasonably dimensioned cities are the substrate of democratic polity,” Sorkin said in 2010. “They’re the only way of taking an adequate inventory of the respiratory functions of humanity…Building cities is not only a profoundly important task from the environmental point of view but one of the most important things that we can do ethically.” His essay “250 Things an Architect Should Know” reflects these priorities, and includes:

39. What the client wants.

40. What the client thinks it wants.

41. What the client needs.

42. What the client can afford.

43. What the planet can afford.

Sorkin’s biography is as colorful and multifaceted as his persona. Born in Washington, DC, his nascent ideas about design and urbanism took form when his family moved to the modernist enclave of Hollin Hills in northern Virginia. After graduating from the University of Chicago, he earned a master’s degree in architecture from MIT and one in English literature from Columbia University.

He also briefly pursued acting in his 20s. The highlight, Sorkin would often gleefully recount, was a role in a local production of The Drunkard at a dinner theater in New Jersey. “Part of our small salary was provided in the currency of dinner, he said at a lecture in Winnipeg, Canada last year. “The hostess carefully supervised, interceding if we ever got close to the pricier items [in the buffet]. Don’t even think of coming near those cocktail shrimp!…We were starving actors and carb-loaded, odd extremists, which left our performance somewhat dyspeptic for the first act of two.”

Sorkin’s performative flair was evident in his lectures. Watching him elegantly construct the arc of an argument was dazzling, even if you didn’t fully concur with his opinions. He taught at the City College of New York for two decades and was a visiting professor at many universities around the world—from Vienna to Wuhan.

Both exacting and generous, Sorkin became a beloved mentor to his staff, students, and writers. I first encountered Sorkin in 2013, as a graduate student at the School of Visual Arts. During the commencement conference of the design criticism program, I witnessed Sorkin efficiently puncture the bloated exhortations of a grandiloquent presenter. He impressed in me a vigilance for well-packaged bullshit so common in design circles. I had found a north star.

For Sorkin, critical writing was a form of activism. In his 2018 monograph What Goes Up: The Right and Wrongs to the City, he explained that “the duty of the writer is ‘to attack current conditions in a manner that will change them,'” quoting the German sociologist Siegfried Kracauer. As the architecture critic of The Village Voice and later The Nation, Sorkin translated turgid “archispeak” (pdf) and contextualized the practice for a wide audience. “It’s relevant for critics—via the medium of the discussion of architecture—to dilate the income gap, the fate of the Earth, urbanization and its discontents…the nature of lifestyle,” he explained at a 2015 talk at Harvard. “It is effectively a way of talking about the social universe and politics.”

Sorkin detested Donald Trump, both as a real estate mogul and a politician. “The Donald inhabits interiors in lieu of an interior life and shows them off with hyperbolic self-celebration,” he wrote in The Nation.

Lampooning Trump Tower in a 1985 Village Voice column, he wrote: “The rank of glyphs bespeaks lakeside Chicago, and the centerpiece of the scheme, the 150-story erection, Trump’s third go at the world’s tallest building…was there ever a man more preoccupied with getting it up in public?”

It wasn’t just Trump. Sorkin also directed his critical gaze toward Barack Obama’s presidential library in Chicago’s Jackson Park, arguing that its location could rob citizens of public space. He also challenged plans for a branch of the Guggenheim museum in Helsinki and somehow managed to foster enough outrage to eventually persuade the Finnish government to scrap the $138 million project.

Sorkin’s vivid prose and peerless acuity for satire are gifts to the reader. His essays are peppered with delicious turns of phrase like “animal goofiness,” “sybarite semi-hipster” (on Donald Trump), or “the modulus of rupture.”

New York, China, and beyond

Sorkin’s professional jet-setting, and hitchhiking days in his youth, exposed him to cultures and curiosities beyond his suburban upbringing. The titles from UR Books, his five-year-old publishing imprint, hint at his wide-ranging sympathies: Beyond the Square: Urbanism and the Arab Uprisings; Downward Spiral: El Helicoide’s Descent from Mall to Prison; Open Gaza.

His architecture practice had been largely focused on China since the mid-2000s, winning projects in Wuhan, Anxin, and the new capital city of Xiongan. Jie Gu, former lead urban designer at his studio, said that Sorkin hadn’t traveled to China recently and likely contracted Covid-19 in New York.

In the introduction to an unpublished book entitled Made for China, Sorkin explained why he was so keen about building in the Far East.

Everybody has a dream of China. Most exciting is the opportunity to work on cities and urban districts from scratch, a blank slate presented to us nowhere else and a possibility that—for all its risks—is indispensable for a planet that is urbanizing at the rate of a million people a week.

Gu told Quartz that his last exchange with Sorkin was eerily foreboding: “He said, ‘If I’m gone, you must use our legacy to keep going the direction that seems best.’ I am using the legacy he left me—his wisdom—to finalize the projects we are working on. I will move forward to design the cities and buildings with high levels of sustainability—to make them safe and welcoming as Michael always pursued.”

Makoto Okazaki, a former partner at Sorkin’s firm, explained that his zeal for sustainability resonated with Chinese officials who were seeking to remedy the alarming environmental degradation in the 2010s caused by the mass migration to cities. “His green city designs were very welcomed,” Okazaki said. So far, not one of these plans has been built. Chinese officials would often take the ideas and redraw them to suit their vision for a “regulated utopia,” as Sorkin put it. Okazaki, who now runs his own practice, also recalls how their office on Varick Street in downtown Manhattan became a magnet for students, interns, and fellow architects visiting from China.

In Winnipeg last year, Sorkin said that he wrestled with the ethics of working with totalitarian governments. “One is always obliged to draw the line, which moves,” he explained. “There are the sympathetic arguments about helping those people who are oppressed…I know radical academics in Israel and continue to have relations with them. I’m ambivalent whether this totalizing boycott cannot find some nuance. I’m not sure at this point.”

Sorkin’s most ambitious project was closer to home. For nearly a decade, his studio has been working on an alternative urban plan for New York City, where he lived for nearly 40 years. In a self-initiated research titled “New York City (Steady) State,” Sorkin’s studio has been collecting ways to make the metropolis completely self-sufficient in terms of its food systems, waste management, water systems, mobility, manufacturing, and local climate. “It’s a design project and a thought experiment,” he explained.

Beyond the litany of accomplishments, which includes more than 20 books, those who knew Sorkin personally will miss his friendship most. “Everyone will pay tribute to him as a great intellect and writer. He was that but also so much more,” said Tau Tavengwa, co-founder Cityscapes magazine, in an email to Quartz. “Michael was funny, generous and a joy to be around—a true humanist. I spent New Year’s eve with him…We laughed all night. That’s how I will remember him.”

Sorkin is the most renowned architect lost to the coronavirus pandemic to date. He is survived by his wife, Joan Copjec, an editor and professor at Brown University.

Earlier this month, 92-year-old Milanese architect Vittorio Gregotti died from pneumonia after contracting Covid-19.