Arcosanti looks much as it did when I visited in 2008: curving vaults, apses and amphitheatres with patterns inscribed in the concrete; circular windows, winding little paths, cypress trees, wind chimes tinkling in the breeze. This experimental city in the Arizona desert, founded in 1970, is like a set from a sci-fi movie for an alien civilisation more enlightened than ours.

And in some ways, Arcosanti is more enlightened. Its utopian community was the brainchild of Paolo Soleri, an outsider architect who looked at America’s unfolding future of consumerism, urban sprawl and environmental destruction, and decided there had to be something better. Arcosanti was a showcase for his concept of “arcology” (architecture plus ecology), which argued that cities should be compact, car-free, low-impact, civic-minded. Planned as a city of 5,000, its population has, however, rarely risen above 150. By 2008, it had come to a standstill. “The main fault is me,” Soleri told me then. He was 89, and seemed resigned. “I don’t have the gift of proselytising.” But this was not the full extent of the problem, it emerged.

In November 2017, four years after her father’s death, Soleri’s youngest daughter, Daniela, published an essay on medium.com, claiming that her father had sexually abused her and attempted to rape her as a teenager. She had told some of Soleri’s inner circle decades earlier, she wrote, and they had done nothing. Daniela likened her experience to that of other women of the #MeToo era who have accused powerful men with cultural capital. “When the abuser is a publicly known, creative person, there is an added layer of complication,” she wrote. “The work itself argues against you, is a source of power for him. You are challenging his successes and everything his work means to anyone who has gained from affiliation, and decided that he and his work are essential to their own identity.”

This was especially true of Paolo Soleri. Scores of people have devoted their lives to his work; some of them continue to live and work at Arcosanti. These were people Daniela had known since she was a child, people she considered her extended family. Some of them knew about her father’s abuses and problematic attitude towards women but, Daniela says, they took little action, even after she went public.

Daniela connects her father’s failings as a human being to the failures of his work – an argument that goes against recent, concerted efforts to separate the two: yes, artists such as Pablo Picasso or Miles Davis behaved monstrously, but their art is a gift to humanity. Daniela argues the opposite of her father: “I believe that the same hubris and isolation that contributed to my abuse also made him, and some of his coterie, incapable of sustained engagement with the intellectual and artistic worlds they felt neglected by.”

In 2008, the largely middle-aged community of Arcosanti had struck me as gentle, open-minded people committed to living frugally and responsibly. They were apprehensive about what would happen to the settlement, and Soleri’s legacy, after his death. More than 10 years on, I wanted to know if Daniela’s public denunciation had had an effect on them? Had they been complicit in Soleri’s behaviour, or were they also victims? Was Arcosanti a relic of the past, or a blueprint for the future? (It has recently hosted festivals and events that draw a young crowd from around the world.) Late last year, I went back to find out.

Paolo Soleri was born in Turin, Italy, in 1919. He arrived in the US in 1946 to work with the renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright, but left Wright’s Arizona office abruptly in 1948, for reasons unexplained. A collision of egos is entirely likely, though Soleri did fundamentally disagree with Wright’s vision for the US city as a sprawling, low-rise, car-dependent suburbia – a model that Soleri described as “an engine for consumption”.

By the mid-1950s, Soleri had established a permanent base in nearby Scottsdale, and married the daughter of a client, Corolyn, known as Colly. Daniela, his second daughter, was born in 1958. (Her sister, Kristine, seven years her senior, refuses to speak publicly about her father.) In a statement of anti-materialist intent, Soleri called his Scottsdale base Cosanti – using cosa, the Italian word for thing.

Throughout the 1960s, Soleri’s output expanded in both quantity and scale. Alongside small architecture commissions, he drew, painted, sculpted and experimented with low-energy design. He produced blueprints for cities and huge allegorical paintings, including a 58ft scroll on the evolution of mankind. He developed an interest in ceramics and bronze casting (his distinctive, handcrafted windbells – which look like souvenirs from Middle Earth – continue to be a source of revenue for his foundation). His reputation also expanded: Soleri’s work was embraced by the design community and US counterculture alike. He received large research grants, put on exhibitions and lectured around the world.

In 1969, Soleri published Arcology: The City In The Image Of Man, a black tome more than 2ft wide, that laid out his philosophy in dense prose and intricate drawings of prototype “arcologies”: mega-cities adapted for different habitats, from canyons to marshlands to volcanoes. They were arguably closer to psychedelic fantasy than serious architectural proposals, but Soleri wasn’t joking. Boosted by his newfound celebrity and wealth, he acquired a plot of desert and, in 1970, the construction of Arcosanti began.

Soleri was also running six-week workshops for paying students and volunteers – mostly from the US, Europe and Japan. About 1,700 of them passed through Arcosanti in its first seven years. As well as learning from the master, they were expected to work, and did so willingly. “You simply picked up a shovel and did what you were instructed to do,” one veteran tells me. “It was a fantastic place to be a kid,” says Daniela, who spent summers at Arcosanti, speaking on the phone from her home in Santa Barbara, California. “Wonderful, exciting, diverse. Very energetic, very enthusiastic, very free. There were so many interesting things happening.”

By the mid-1970s, Soleri had attracted a community that ranged from serious collaborators to acolytes and strays. He was in his 50s and becoming more confident in his own ideas, and less tolerant of dissent, says Daniela. “If there was ever a significant challenge, that person would have to leave.”

Daniela was moving into adolescence, which is when the abuse started. “I don’t know that I want to go into precise details,” she tells me, “but definitely violations of my body, and of my person as an independent young woman, both hands on and hands off.” It happened about once a month, in her home. “It followed the pattern that you now read about so often where you just freeze… You really do freeze.”

The breaking point came in 1976, at an exhibition in Rochester, New York. Daniela was sharing a hotel room with her father. “That’s when he tried to rape me,” she says. “I was 17.” It took her years to recover and process what had happened, she says. “Those kinds of experiences undermine your sense of self, your sense of agency, and your sense of worth.”

Daniela did not completely cut ties with her father. After two years studying, she returned to Arizona to work for the Cosanti Foundation for six months, during which time she saved enough to go travelling in Africa for three years. She returned when her mother was diagnosed with colon cancer, and nursed her for nine months until her death in 1982. When I ask if her parents were happily married, Daniela laughs. “It was a work partnership devoted to him – Paolo spent all his time on his work; my mother also spent all her time on his work. She was a very social, gregarious, very warm person. There’s a good case to say that she worked herself to death for him.”

Daniela established herself as an academic, specialising in agriculture and food systems, but continued to be involved with her father’s work “in a peripheral way”. In 1993, during a discussion about Soleri’s attitudes towards women, she told a small group of people at Arcosanti about the abuse. The news was “unwanted information”, she says. “In retrospect, I’m surprised no one thought, ‘Gosh! As grownups maybe we should have said something.’ But when I did tell them, I made it very clear that I wasn’t OK with it, and that I found his treatment of women reprehensible.”

Nobody has disputed the truth of Daniela’s claims, but her continued contact with her father led some to question her allegations. Such behaviours are often used to undermine survivors of abuse: if it was so bad, how come you went back? Why did you not speak out sooner? It was partly a matter of her commitment to her father’s work, she says. “I was still such a believer that my workaround at the time was to think my greatest contribution would be to just bury it. That’s my little burden to bear for the greater good.”

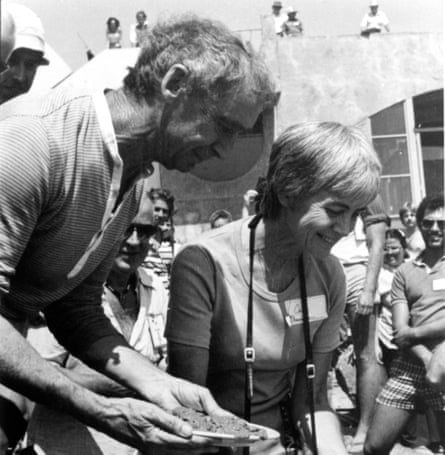

When I interviewed Soleri in 2008, he was stewarded by Mary Hoadley, who dutifully prompted and finished his thoughts for him. Her husband, Roger Tomalty, gave me a tour of Soleri’s 1960s works at Cosanti. Now in her 70s, white-haired and suntanned from a lifetime spent working outdoors, she still works for the Cosanti Foundation, as does Tomalty.

Hoadley first met Soleri in 1965 and, like many others, was captivated by him. “He was really dynamic, a little elf-like man,” she says, when we meet last year. “Quick to be angry, quick to forget, really focusing on the work.” We are sitting in her former apartment at Arcosanti – an irregular warren of concrete rooms overlooking the apse. When she first arrived, it was all desert. “My mother helped me trowel this concrete floor,” she says, looking down.

Hoadley recalls Daniela almost like a younger sister (she affectionately calls her “Dada”) and sympathises with her plight. “The atmosphere was so idolatrous of Paolo – so who to talk to?” Hoadley remembers when Daniela revealed she had been abused: “We were all just sort of bowled over. I sometimes think, why, at the time, didn’t I just go, ‘Oh my God, this is awful’? Why didn’t I delve into it? She might have dropped the information hoping we would come to her aid, and perhaps we didn’t hear that request, or maybe it was too scary to act on at the time. In hindsight, given everything that’s happened, I wish we’d really delved into it.” Hoadley says she took Daniela’s continuing contact with Soleri as a sign that she had forgiven him.

Another early Arcosanti recruit was Tomiaki Tamura, a trained architect from Japan, who visited out of curiosity in 1975. “I wasn’t exactly sure he had the right answers, but he asked lots of good questions,” Tomiaki tells me. He became Soleri’s assistant. For many years, it was just the two of them designing the city. “It was not really a collaborative process,” Tomiaki says. “I could make suggestions but he always had the bottom line.” Despite having worked alongside Soleri for over 35 years, Tomiaki spent little time socialising with him. “We had dinner every once in a while, but not often. He was pretty much a loner. So am I.”

Tomiaki says he had no inkling of Daniela’s experiences at the time: “I really didn’t have any control, I feel, over this whole unfortunate situation, but, at the same time, one has to take responsibility.” He still lectures on Soleri’s work, but always ends by making clear there was “a side of Soleri that was not very good”.

Many Arcosanti veterans agree that Soleri was not particularly concerned with the social aspects of his urban experiment. “He dictated the design but he didn’t dictate the lives of the people who participated in it at all and that, to me, was a very, very good setup,” says Sue Kirsch, who manages Arcosanti’s archive. Kirsch first visited Arcosanti from Germany in 1978, with her three-year-old daughter. She has lived here, on and off, for 30 years, during which time, like most residents, she has performed various roles: cooking in the communal kitchens, gardening, purchasing, coordinating workshops, conducting guided tours. There are no schools or shops, only a petrol station and a bar on the highway a couple of miles away.

Kirsch was not close to Soleri. “He was a very private person. He would set a fairly high bar for the tone of discussion. It would not be about the president or politics or something stupid, it would be: OK, we are mankind. Where did we come from? Where are we going?”

One social aspect that did interest Soleri was women. “If there was a meeting and there was a beautiful young woman, he would be a little bit flirtatious,” says Kirsch, “but to me it was that ‘typical old Italian guy’, kind of rooster behaviour, so I never took it that seriously.” Soleri’s status, combined with Arcosanti’s workshop programme, ensured a steady flow of admiring women, decades younger than him. “There were many instances of women being courted and, uh, whatever the word is… affaired,” says Hoadley. There is nothing to suggest these liaisons were not consensual, though from today’s perspective, they could be characterised as exploitative.

There was also the issue of the life drawings. Soleri would regularly draw nude female models, who responded to his flyers calling for “women, aged 21 to 41”. Some enjoyed the experience and maintained that Soleri behaved appropriately. Others tell a different story. Writer Margie Goldsmith modelled for Soleri in 2006. Having finished his second sketch, she recalls, Soleri, then 87, said to her: “May I have the privilege of kissing your nipples?” Goldsmith refused, put on her clothes and left. Daniela said she had heard “many other stories” similar to Goldsmith’s. “This has been going on for a long time, and the people in what I call the inner circle, they knew about it.”

In October 2010, Daniela resigned from the Cosanti Foundation board, again citing her father’s abuse. “I found out that someone who had been there almost my whole life was one of the people that Soleri was having relations with, and that same person was also quite cruel to my mother in a very juvenile way.” She wrote to the board that she was “disturbed” by how they had handled her information and father’s behaviour. “I am no longer willing to cover up and accept things that are to me unacceptable.”

After Daniela’s resignation, the board decided it would be best if Soleri stepped down as chairman and ceased his life drawing; but it made no public statement on the matter, not even after his death two years later. “I thought, when he died, then things would be sorted out. They didn’t do anything,” says Daniela. “There were eulogies, hagiographic readings, and on and on. [In October 2017, the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art opened a major retrospective titled Repositioning Paolo Soleri: The City Is Nature.] Nothing happened until I published that essay.”

It was only when the local press began asking questions that the Cosanti Foundation issued a statement. “We are saddened by Daniela’s trauma,” it read. “Her decision to speak out about her father’s behaviour towards her helps us confront Paolo Soleri’s flaws, and compels us to reconsider his legacy… We support and stand firmly with Daniela.”

“That was an interesting way of putting it,” says Daniela sarcastically. “That’s a strange timeline for making assertions about ‘standing firmly’.”

My return to Arcosanti last year coincided with Convergence – a three-day festival of “counterculture, co-creation, art and music”, now in its third year. In contrast to Soleri’s “old man” values, the vibe is a mix of steampunk, eco-hippy and Burning Man. There are talks and workshops on inclusivity, racial justice, self-realisation, sustainability, plus live music and hip-hop poetry. The crowd is noticeably youthful and diverse. One visitor tells me he found Arcosanti via Instagram. There is an evening ceremony with a Native American flautist playing as a red full moon rises. Few people seem to be familiar with Paolo Soleri and almost none are aware of the abuse allegations. The only mention of Soleri is during a panel discussion on the future of Arcosanti, where one veteran describes him as “a benevolent dictator”.

Arcosanti’s permanent population is now about 80 – a third of whom are recent, young arrivals. It is appealing to a new demographic, says Tim Bell, the foundation’s communications director, who moved here two years ago. A former actor from New York City and a self-described “Burner” (veteran of Burning Man), 32-year-old Bell was seeking alternatives, he says. “I watched my parents lose their home in the 2008 crash and move into a trailer park and that was really difficult. It left me with this want for something better, for myself and my kids and their kids. That’s why Arcosanti spoke to me.” His generation is going through a similar process of re-evaluating society as their 1960s forebears, he suggests. He sees Arcosanti as a potential “caravanserai on the search for meaning”.

Patrick McWhortor, the Cosanti Foundation’s chief executive, agrees: “Paolo was ahead of his time in his thinking. We all should have listened to him 60 years ago. The planet is paying the price. Now it’s urgent that we address these issues, and I think young people feel that urgency.” McWhortor was appointed in 2018 to bring fresh thinking to Arcosanti. The 54-year-old has a background in non-profit organisations and describes himself as a “change agent”.

“The work to build Arcosanti was amazing in terms of the vision and energy and passion across the last 50 years,” he says. “What wasn’t really built was the organisation to support it all on a permanent basis. We had forgotten to reach out to the wider world. I want to get us back on the upward curve on that.” McWhortor acknowledges that the Cosanti Foundation has some reputational damage to restore, while defending the mission of Arcosanti. “The ideas and the vision that Paolo inspired – that work is important regardless of anything Paolo ever did personally. So to punish us and the people who are trying to advance that work because of his behaviour, really, to us, doesn’t make sense,” he says.

Soleri’s diagnosis of civilisation’s ailments was largely correct. For proof, one need only look at Phoenix, the fifth-largest metropolitan area in the US (Scottsdale has been absorbed into it), and one of the least sustainable cities in the US: exactly the type of sprawling, car-centric “engine for consumption” that Soleri warned against. His alternative might not have all the answers – who knows how Arcosanti might function as a city of 5,000 people? – but from today’s perspective it looks like a path not taken.

Perhaps the flaw in Soleri’s vision was not so much his inability to proselytise as his assumption that he could change the world through his genius alone. “Ego drives a lot, and is necessary,” says Daniela. “But when you can’t see outside of it, that’s when you have trouble.” In the absence of any social or communal organisation, she adds, Soleri’s utopia defaulted to plain old mid-20th century patriarchy: “Paolo always said, ‘I’m building the instrument; you have to play the music.’ But he would dictate every single note of music that was ever played. It was the nature of his personality, and the people that gathered around him, that prevented him from having peers who would challenge him. That could have helped him and improved it.”

If anyone is qualified to assess the success of Soleri’s “urban experiment”, it is surely Daniela. She has spent most of her life weighing it up. In her view, “70% of it is really valuable and helpful and realistic, and 30% of it is poisonous”. Rather than attempt a surgical separation of artist and work, or dismiss Soleri’s legacy wholesale, it is perhaps more worthwhile to identify what could still be of value.

Daniela no longer has any involvement with the Cosanti Foundation. “I just stay away because it’s too sad to me,” she says. “There was the personal loss, in terms of all the friendships and family. But also there was this institution that I really believed in strongly.” She still believes in a positive way forward: “But it has to be honest. It has to be clear about what happened and how it was handled, and what that meant – not in terms of me and people who were there, but in terms of how the institution functioned. His work deserves recognition. But I believe its value should never negate his faults.”