Harry Kupfer, who has died aged 84, was a towering figure in opera production with a career spanning 60 years. A native of Berlin, for the first two decades he worked largely behind the iron curtain, but a handful of productions in the west in the 1970s led to a landmark Flying Dutchman at the Bayreuth festival in 1978, followed by an equally trailblazing staging of Wagner’s Ring there in 1988.

The two greatest avowed influences on Kupfer’s dramaturgy were Walter Felsenstein and Bertolt Brecht – he called them his “spiritual forefathers”. From the former (though he never worked directly with him) he imbibed the principles of realistic music theatre (as opposed to singers’ opera), emphasising the importance of character, motivation and dramatic immediacy. From the latter he inherited the idea of distancing the audience from the action on stage: theatregoers should be critical and engaged rather than passive and emotionally manipulated. The result of this twin influence was a style that was intellectually rigorous but at the same time powerfully communicative.

The Bayreuth Flying Dutchman that brought him to worldwide attention provided an incisive psychological reassessment of the predicament of the heroine, Senta, in terms of socially induced alienation and neurosis, but also an electrifying theatrical experience. In the same year he made his UK debut with an Elektra for Welsh National Opera (WNO) that matched the score’s savage violence with a mise-en-scène depicting a barbaric slaughterhouse, littered with blood-spattered carcasses. His characteristically polemical Fidelio, also for WNO (1981) alluded in its final tableau to freedom fighters past and present, while his Pelléas et Mélisande for English National Opera (1981) dispensed with naturalistic props, treating the work as an allegory akin to Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain, with its metaphors of psychosomatic illness and its inhabitants reluctant to leave the refuge of the sanatorium.

Kupfer’s Bayreuth Ring was a densely allusive, socially critical exploration of the cycle that integrated mythological and contemporary planes so as to address the issues of accumulated wealth and power, ruination of the natural environment and global destruction, while remaining faithful to the work’s timeless universality. Before a note of music was heard, a post-holocaust group of men and women stared bitterly out at the audience, suggesting that we were observing a true cycle of human history – one we have the power to transcend if only we would learn the lesson. The ash tree in Die Walküre was dead and the forest in Siegfried had clearly been laid waste by an ecological disaster. The image of Valhalla as a Manhattan-style skyscraper alluded to the role of capital in this apocalyptic scenario. Replete with socio-political awareness, psychological observation and striking theatricality, it remains one of the key productions in the Ring’s stage history.

Kupfer spoke of his approach to production as beginning, perhaps surprisingly, not with the text but with the music. “All my fantasy comes when I hear or read the music,” he said. Having attempted to grasp the composer’s meaning, he then turned to the text, creating a dialectical relationship between the two.

Impatient with those who wanted opera to provide a haven from politics, Kupfer also spoke of his desire to build a bridge from the time of a work’s creation to the present day and of his wish to provoke the audience to find its own context for a work. He was one of the finest exponents of what is known in German as Personenregie (“direction of the characters”), encompassing a fusion of text, music, gesture, mime, characterisation and stage choreography.

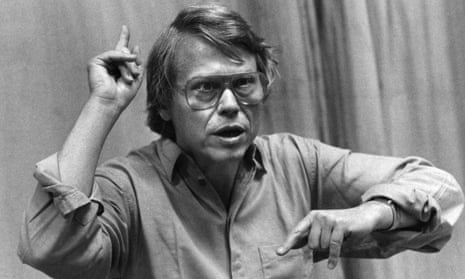

Always well prepared himself, he expected his singers to know their parts perfectly by the first rehearsal. While his approach was undoubtedly serious, he had a wry sense of humour and his style was explicatory rather than dogmatic. In his prime he was energetic and constantly mobile, except when drawing on his pipe. In the rehearsal room he was demanding but endlessly stimulating, working in meticulous detail with his singing actors to tease out textual nuances and embody them with appropriate stage action.

Both John Tomlinson and Anne Evans, his Wotan and Brünnhilde in the Bayreuth Ring, have spoken of his remarkable ability to develop original but convincing characterisations in collaboration with his performer colleagues. A notable example was seen in Act III of Die Walküre. According to an aperçu of Kupfer, it gradually dawns on Wotan that his fathering of a noble race will one day provide the hero required to deny Alberich the ring and create a new generation free of its curse. Tomlinson’s ecstatic demeanour and Evans’s portrayal of the Valkyrie, “like a butterfly emerging from a chrysalis,” as she has described it, combined with singing and playing of the highest quality, produced an enactment of shattering potency.

Kupfer was born in Berlin and was an opera enthusiast from an early age. He often absented himself from school on days when he could hear Der Rosenkavalier or Tristan und Isolde at the Staatsoper under Erich Kleiber. In postwar East Germany, after studying theatre science at the Hans Otto Theaterschule in Leipzig, he became an assistant at the Landestheater in Halle, where he made his production debut with Rusalka in 1958. He was then successively Oberspielleiter (senior director) at the Theater der Werftstadt in Stralsund (1958–62), senior resident director at the Städtische Theater in Karl-Marx-Stadt (now Chemnitz; 1962–66) and opera director of the Nationaltheater in Weimar (1966–72). From 1967 to 1972 he also taught at the Franz Liszt Musikhochschule in Weimar.

In 1971 he made his debut at the Berlin Staatsoper with Die Frau ohne Schatten and the following year was appointed opera director at the Dresden Staatsoper, remaining in the post until 1981 and winning renown for himself and the opera house with adventurous programming and challenging productions of works such as Moses und Aron (1975), Tristan und Isolde (1975) and Simon Boccanegra (1980).

From 1981 he was director of Komische Oper Berlin and professor at the Musikhochschule Hanns Eisler, also in Berlin. A typically successful production at the Komische Oper was that of The Marriage of Figaro (1986), which highlighted the social repression and chauvinism of the world depicted by Beaumarchais. In 1989 two of his many Komische Oper productions were brought to Covent Garden: a Bartered Bride that got behind the folksy facade to the underlying social realities, and an Orfeo ed Euridice that addressed the dilemma of the artist in society, relocating the myth against a bleak background of contemporary urban decline.

With the conductor Daniel Barenboim he built up a complete cycle of the major Wagner works at the Berlin Staatsoper in the 90s. Parsifal was one of several works he revisited on more than one occasion. His third production, for Tokyo (2014), placed a trio of silent Buddhist monks on stage, gradually drawn into the action and acting as spiritual advisers to Parsifal as he achieves enlightenment. His Rosenkavalier for Salzburg in the same year was representative in its deftness of social observation and ravishingly executed, with scenography by his long-term designer Hans Schavernoch.

New works he premiered included Udo Zimmermann’s Levins Mühle (Dresden, 1973), Penderecki’s Die Schwarze Maske (Salzburg, 1986) – for which he collaborated with the composer on the libretto – and Aribert Reimann’s Bernarda Albas Haus (Munich, 2000).

He continued to work on the international stage until his death, returning to the Komische Oper with an acclaimed production of Handel’s Poro in 2019.

His wife, the soprano Marianne Fischer, died in 2008. He is survived by their daughter, Kristiane.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion