As a long-standing supporter of the rights of indigenous peoples, Conrad Gorinsky, who has died aged 83, was the inspiration behind the creation of the campaigning human rights organisation Survival International and, unwittingly, one of the catalysts for the introduction of the UN’s Convention on Biodiversity, which attempted to protect the interests of those with traditional knowledge of the properties of plants.

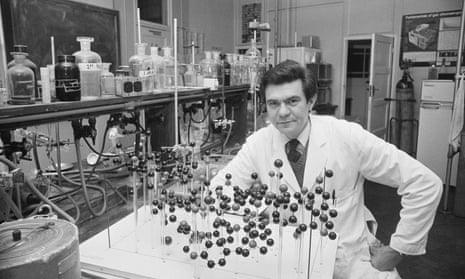

Born of part-Amerindian ancestry, on the northern edge of the Amazonian rainforest in Guyana, South America, Gorinsky used the medical training he received in Britain to isolate the active constituent both of the nut of the greenheart tree, which he called rupununine, and of the barbasco bush, which he christened cuaniol. Hoping that both chemicals would be of use in developing new medicines, he filed for patents and began to make contact with drug companies.

His plan, he claimed, was to use the patents to prevent exploitation of the plants by governments and multinationals – and to help tribes sell their knowledge while establishing legal title to their heritage. Any money received, he said, would be shared with the tribes. But when it emerged that Gorinsky had not sought permission from local people to patent the plants – and that he also had no agreement in place to pay them for their knowledge – a massive row ensued.

From being a human rights defender and a hero of the global environment movement, he was swiftly branded by politicians, scientists and environmentalists as a “bio-pirate”, out to exploit the knowledge of indigenous people for financial gain.

The case had far wider implications, however, than the damage to Gorinsky’s reputation. It helped to stoke mistrust between wealthy and developing countries that has soured many environmental negotiations, and it also fed into the UN’s deliberations over what to do about the patenting of drugs derived from the knowledge of indigenous communities. That led to the 1992 Convention on Biodiversity, which essentially nationalised plant resources and forbade the patenting of organic ingredients by individuals.

Gorinsky might have allowed himself to be wryly amused at the thought of becoming a villain whose actions needed to be reined in by that convention, for he had devoted much of his life to championing the rights of indigenous peoples. The son of Cesar Gorinsky, a Polish cattle rancher and gold prospector, and Nellie Melville, a half-Atorad tribeswoman, Gorinsky was born in Parubaru, in the far south of what was then British Guiana (now Guyana), close to the Brazilian border.

In later years he recalled how even as a youngster he had been fascinated by the medical potential of the natural drugs and poisons found in the region’s plants. His mother’s tribe had been all but wiped out in the 1918 flu pandemic, and the survivors were adopted by the larger Wapishana group. The young Gorinsky said he would watch the Wapishana women chewing the nuts of the greenheart tree to control menstruation, and making infusions of its bark to prevent malaria.

After Jesuit school in the capital, Georgetown, at 17 Gorinsky travelled to the UK, where he enrolled at night school. He then studied biology at Oxford University, going on to do a PhD at St Bartholomew’s hospital medical college in London, where he researched the plants he had known as a child. He made a number of visits back to South America, where his family background ensured that he was welcomed into the local Wapishana communities to learn first-hand about the use of plants. He also became a lecturer at Oxford, building his own ethnobotanical laboratory.

It was on one of his expeditions up the Negro river and down the Orinoco in 1968 that the idea of creating Survival International came into being. Aboard a hovercraft on its 2,000-mile journey over rapids and through virgin Brazilian rainforest were scientists, reporters, engineers, and soldiers – plus Gorinsky and the explorer and conservationist Robin Hanbury-Tenison, both of whom had both joined the expedition to investigate how tribes used forest plants as medicines.

On the trip the pair discussed at length the plight of Brazil’s indigenous communities and the fact that they were losing both their lands and their lives to loggers and ranchers, who were tearing down and burning their forests. On their return to London, and in response to a shocking 1969 Sunday Times article giving evidence of systematic torture and genocide of tribal peoples, the two joined the environmentalist Edward Goldsmith, the anthropologist John Hemming and others to set up the Primitive Peoples Fund, which later became Survival international.

Gorinsky, said Hanbury-Tenison, was the inspiration behind the whole venture, arguing that the new organisation should “strive to protect the rights of Indians to their lands, their cultures and their identity, and that it should foster respect for and research into their knowledge and experience so that ... we should learn from them and so contribute to our own survival”.

In a series of later visits to Guyana, Peru and Brazil to study medicinal plants, Gorinsky became convinced that indigenous Indians were the undisputed authorities on the environment, but that their traditional knowledge was becoming extinct. Feted by environmental groups, he compared the Amazon forest to a library and its tribes to librarians – and became one of the first people to argue that they should benefit financially from their knowledge of nature.

At that point he little anticipated that he would soon be accused of betraying the very people whose rights he had spent so much time campaigning for. After returning to Britain from South America with plant samples in the 1980s, Gorinsky was eventually able to isolate rupununine and cuaniol from the material at his disposal – the former he hoped could treat diseases such as malaria and cancer and the latter might be able to unblock arteries.

Unfortunately for Gorinsky, the 80s had seen the beginning of a gene rush to the world’s rainforests, with large pharmaceutical companies seeking the next wonder drug. “Bio-prospectors”, mostly working independently, were scouring the forests quite legally, identifying the medicinal plants used by shamans and selling them on to US and European corporations without rewarding the tribes. While Gorinsky tried to distance himself from the bio-prospectors, he nonetheless filed patents for his active ingredients, and began to explore how these could be exploited.

Despite his protestations of innocence, once accused of being a bio-pirate Gorinsky’s fall from grace was swift. On a visit to Venezuela he was condemned as a “colonial scientist” and given 24 hours to leave the country. Worse, the Wapishana, among whom he had grown up, accused him of stealing their knowledge and, with the help of western environmentalists, contested both patents.

Gorinsky was badly hurt. He had financed his research himself, taken no money and broken no laws, but had been accused of a serious breach of trust. His motives had been pure, he said, but he had been naive. Although he could have found a way round the UN Convention on Biodiversity because his patents were held in the US, which did not recognise the convention, eventually he let both of them lapse and neither he nor the Wapishana earned anything from them.

Afterwards he continued to research forest plants in his own laboratory; the concept of ethnobiology is widely taught today thanks partly to his work. He became president of the Foundation for Ethnobiology charity, which he had set up in 1988, and, with money from the UK government’s Darwin Initiative and help from Operation Raleigh (now Raleigh International), he recorded the uses of many rainforest plant species.

He claimed to the end that he would never have betrayed the communities whose heritage he shared, but while he was known to be a world authority on the medical use of tropical plants and a great defender of indigenous groups, the damage had been done.

In 1967 he married Beatrice Woolhouse, a lecturer in crystallography, who survives him, as do their three children, Julian, Roland and Christina.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion