The Fraught Effort to Return to the Moon

NASA wants to put people back on the lunar surface in 2024, but it doesn’t have the budget.

The 50th anniversary of the moon landing is almost here, and NASA has gone all-out for the occasion.

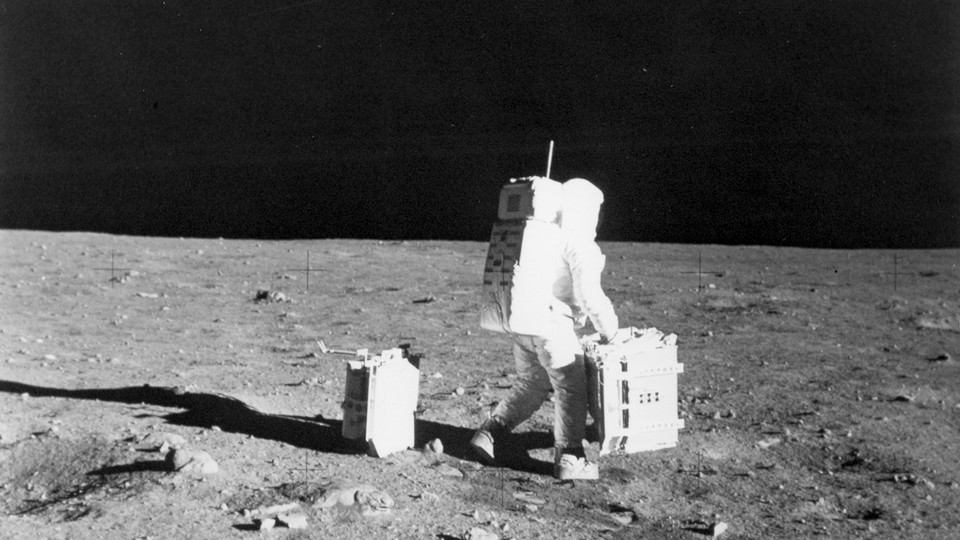

The agency has been celebrating the memory of Apollo 11 for months. It has published a steady stream of archival photos and footage of the astronauts suiting up, blasting off, and posing on the lunar surface with the American flag, a pop of color against an expanse of gray. It refurbished the room at the Johnson Space Center where Mission Control monitored the journey so that now it looks the way it did in 1969, down to the coffee cups, clipboards, and packs of cigarettes. NASA headquarters even asked every communications officer at the agency to be “mindful of posting evergreen materials during the next few weeks that could get better attention once we’re past that spotlight event,” a spokesperson told me. Apollo 11 is NASA’s most famous mission, and the moon landing is one of the most defining moments in human history. It’s been moon time, all the time.

But behind the celebrations, the atmosphere was less harmonious. As NASA commemorated one mission to the moon, the future of the next one seemed precarious.

The Trump administration wants to return Americans to the moon, a place they haven’t been since 1972, in five years—during President Donald Trump’s second term, if he is reelected. Right now, the agency doesn’t have the money to make it happen. In May, the White House asked Congress for an extra $1.6 billion in NASA’s next budget to start funding this effort, which would cost $20 billion to $30 billion and, unlike the Apollo program, rely heavily on technology bought from private companies. Astronauts would land near the south pole this time, where they could theoretically make use of water frozen in the surface. And the crew would include, for the first time, a woman. A mission to Mars—the focal objective of the Obama administration—will come later, after astronauts show they can safely live and work on the moon.

As Congress figures out funding for the next year, NASA officials have spent the past several months talking up the new mission—named Artemis, after Apollo’s sister in Greek mythology. As with the Apollo-anniversary coverage, everyone seemed to be on message. Until, that is, the person who ordered the mission strayed.

“For all of the money we are spending, NASA should NOT be talking about going to the Moon - We did that 50 years ago,” President Trump tweeted in June. “They should be focused on the much bigger things we are doing, including Mars (of which the Moon is a part).”

The tweet stunned the NASA community. Trump has been enamored of the Mars-mission idea since he took office, and once asked a NASA official whether the agency could put people on the red planet by the end of his first term. But that conversation unfolded in private and was only revealed in a tell-all book by a former White House official. In contrast, there was no denying the blustery Mars tweet, nor the blatant contradictions in its message.

“I called him after that,” Jim Bridenstine, the NASA administrator, told me of the president. “And I was very clear, ‘I want to be sure we’re in alignment.’ And he was very clear with me: ‘I know you’ve got to go to the moon to go to Mars, but you need to talk about Mars.’”

Mars is the “generational achievement that will inspire all of America,” Bridenstine said Trump told him. In his tweet, Trump seemed to acknowledge that the moon matters when it comes to making it to Mars—“of which the moon is a part.” But Mars, it seems, is a better sell.

Then, last week, another shocking moment: Bridenstine announced he was demoting NASA’s head of human exploration. William Gerstenmaier has worked at NASA since 1977, guiding the agency through spaceflight triumphs and tragedies, and shifting gears every time a new president comes along with different ideas for the nation’s space priorities. The morning of the announcement, Gerstenmaier was on Capitol Hill, testifying before members of Congress about the 2024 plan.

Although the decision came from Bridenstine, Gerstenmaier appears to be a victim of the White House’s impatience with NASA’s progress on the moon mission. The development of the rocket that is supposed to launch the Artemis astronauts, like most major exploration efforts in NASA history, is over budget and years behind schedule. Vice President Mike Pence, who gives the big space-policy speeches on behalf of Trump, is “livid,” according to The Washington Post. “If NASA is not currently capable of landing American astronauts on the moon in five years,” Pence said earlier this year, “we need to change the organization, not the mission.”

Bridenstine insists that, despite the sudden personnel shake-up, everything is fine at NASA. “We love the work [Gerstenmaier’s] done, and we’re grateful for his service to NASA and to the country,” Bridenstine told The Verge after the announcement. “But I think we’re at a time when we need new leadership.”

Bridenstine attributes the rush to the unpredictable tides of electoral politics; the next president could slash the 2024 moon plan, just as President Barack Obama canceled President George W. Bush’s moon plan in favor of Mars—a plan that didn’t make it very far, either. NASA has already seen several shifts under this administration alone. The goal was to return to the moon from the start, but the deadline jumped from 2028 to 2024 this spring. Mars seemed almost an afterthought at first, a next step for humankind that seems so inevitable that the details can be worked out later; now it’s a pressing imperative that the president wants to make sure the public hears plenty about.

Bridenstine is already carrying out Trump’s latest request. Yesterday, during a press conference about the Apollo anniversary, the administrator teased the release of a new Mars plan. “We are working right now, in fact, to put together a comprehensive plan on how we would conduct a Mars mission using the technologies that we will be proving at the moon,” Bridenstine said. “Remember, the moon is the proving ground. Mars is the destination.”

Bridenstine even mentioned a long-held target date for human exploration of Mars, despite the fact that a NASA-commissioned report recently concluded it isn’t possible, even without budget constraints. “I am not willing to rule out 2033 at all,” he said. The faster NASA gets to the moon, Bridenstine said, the faster it gets to Mars.

The Trump administration faces a public skeptical of both destinations. According to a recent poll, 78 percent of respondents have a favorable view of NASA, and a majority say the government is spending too little when they’re told that the agency’s annual funding accounts for half a percent of the national budget. But just 42 percent think NASA should go to the moon in 2024, another recent poll found. A similar proportion of people think neither Mars nor the moon should be a priority. Even the two living Apollo 11 astronauts, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, think the United States should head to Mars instead of the moon.

It is difficult, even foolhardy, to predict whether NASA astronauts will be on the moon for the next big Apollo commemoration. In the decades since the historic mission, the agency has pressed deeper into the solar system and sprinkled spacecraft on and around other worlds. By the 65th anniversary, if everything goes according to plan, there will be a little drone hopping around on a moon of Saturn, looking for signs of life—not the fossilized type, but the kind that swims or squirms today. And what of the world next door? Will people be celebrating down here, or will a few lucky representatives mark the occasion on the moon? It’s not an impossible future; after all, they’ve been there before. But it is by no means guaranteed.