This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

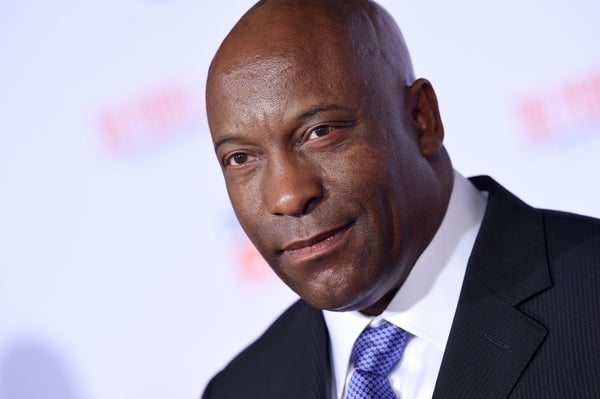

The recent death of John Singleton

, the first and youngest African American to be nominated for an Oscar for Best Director, sent shock waves throughout Hollywood and beyond. Singleton died at age 51 after having a stroke on April 29. Strokes are often associated with uncontrolled hypertension, also referred to as high blood pressure.

As a nurse with decades of professional nursing and community service, I have seen the devastating effects of hypertension more times than I care to admit. Hypertension has always been a leading cause of illness, disability and even death in the African American community. While there are numerous reasons for uncontrolled hypertension, the disorder when not properly treated or managed can lead to a number of adverse consequences including strokes.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

This is particularly grim news for African Americans

, who have the highest prevalence of hypertension in the world. Even John Singleton’s fortune and fame could not protect him from the condition. Hypertension, the silent killer, was slowly taking a toll on his body. Singleton's family has publicly asked black men to take better care of themselves by getting their blood pressures checked and treated if needed.

Since my days as an undergraduate nursing student, I have studied the predictors of hypertension management in inner-city residents. Just two days after Singleton’s passing, I visited a community-based clinic that provides needed health care services to a population of predominately African American men who are reentering society after being incarcerated. One patient I observed had stopped taking his hypertension medications because of the side effects, specifically impotence. His friends had encouraged this decision because of their personal distrust of medical interventions.

Thankfully, the nurse practitioner provided counseling and the assurance she could find a different medication with fewer side effects. I admired how the nurse, a white woman, had tackled such a sensitive and personal issue with a young African American man. Such crucial conversations are potentially lifesaving, but they might take place more often—and more effectively—if we had more African American physicians.

In this way, Singleton’s death not only underscores the hypertension crisis in the African American community, but also sheds light on the poor health status of African American men in this country. In general, black men have the

lowest life expectancy, living 7.1 years less than other ethnic groups. African American males are less likely to have access to tailored medical and social services that take into account their unique health related needs.

Along with discussions on hypertension and stroke in the African American community,

Singleton’s death has sparked a conversation regarding the importance of having a match between a patient’s racial identity and that of his physician in improving the health outcomes of African American males. There is a paucity of minority providers who can care for the growing numbers of African American men diagnosed with hypertension or any of the other leading causes of morbidity and mortality for this population. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, in 2013, 4 percent of the physician workforce was black or African American. Of note, 13 percent of the nation’s population was black or African American in 2013.

Experts note that the number of black males entering medical school has been declining since 1978. In 2015, for example, the entering class of 20,000 medical students included only 515 African American men. Experts committed to ensuring a diverse workforce have declared the absence of black men in medical schools an American crisis, one that demands our immediate attention in building a pipeline of applicants who can successfully apply to and matriculate from medical school.

The current shift in the nation’s demographics and the ongoing disparities in health status and health outcomes for African American men demand that we do more to diversify the nation’s health care workforce. Barriers such as high student debt, limits in academic preparedness, and inadequate support from and exposure to successful role models must be factored into our efforts to attract and retain entry of all minorities into the health professions.

While there is an urgency to reverse the ongoing shortage of African American providers, we must remain vigilant in ensuring that all providers regardless of cultural or racial ethnic identity are able to provide culturally sensitive care to all patients. Anything less will be counter to our efforts to eliminate health disparities and achieve health equity.