The impresario Victor Hochhauser, who has died aged 95, made possible performances by leading figures of the worlds of classical music and ballet in Britain, sometimes also in Israel and in the former communist bloc countries. Many of them became personal friends. In the decades following the second world war, Victor made it his business, and his pleasure, to bring such great talents to the widest audiences.

To that end he ventured behind the iron curtain and to China, opening western doors for performers from the Soviet Union such as Rudolf Nureyev and the pianist Sviatoslav Richter, the Bolshoi and Kirov ballets and Chinese opera. Working as a team with his wife, Lilian, Victor developed a remarkable record in negotiating with the Russians, sometimes in spiriting artists out of the country, always nannying them and nursing their supersize egos.

Yet Victor did more than cater for the elites. It was always his ambition to make the performing arts more accessible to wider audiences. His Sunday evening concerts at the Royal Albert Hall in London, often derided by the critics as second-rate potboilers, popularised classical music long before the emergence of the Three Tenors. Victor was also the first to stage opera for mass audiences at the former Earls Court exhibition centre and in what is now Arena Birmingham.

The impresarios’ club is small, its members always competing for artists and auditoriums. As a young man Victor certainly had no burning ambition to penetrate this circle. His priorities in 1945 were far more concerned with his Jewish faith. He had been born in Kosiče, in what is now Slovakia. His family were devout Jews – his grandfather had been chief rabbi of Hungary. But his father was an industrialist, and in 1938 emigrated to Britain while it was still possible to save the family from Nazi persecution.

The young Victor was sent to study at a Jewish seminary in Gateshead and went on to work as a fundraiser at a London synagogue for Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld. It was in that capacity that he set out to stage a charity concert – and in the process discovered that he possessed a hidden talent for promoting musical events. In March 1945 he was able to hire the Whitehall theatre in London; and because his father knew the father of the pianist Solomon Cutner, who always appeared professionally as Solomon, the great man was persuaded to perform.

On the strength of that evening’s success, Victor borrowed £200 from his father, hired the Albert Hall for £30, booked the London Symphony Orchestra for £60 and in May staged the first of a series of concerts that featured such names as the violinist Ida Haendel and pianists Eileen Joyce, Louis Kentner and Benno Moiseiwitsch. It was always sold out, and in 1946 he secured the conductor Sir Thomas Beecham for a season of concerts. “It all seemed so easy,” Hochhauser reflected many years later.

In 1947, Victor felt sufficiently secure to organise a Richard Strauss festival, with the composer himself sharing the conducting with Beecham. The following year, he also approached Harold Holt, London’s leading impresario, to ask if he could borrow one of his artists, Yehudi Menuhin, for a charity concert. “Holt saw me as a novice, said ‘so what?’ and let me have Menuhin at a reduced fee. And that is how I got Menuhin,” Victor said many years later, still savouring Holt’s misjudgment.

Menuhin went on to play under the Hochhauser management on many occasions, and they became good friends. But those concerts in 1948 were unique: the Vienna Philharmonic came on its first postwar visit, playing under Bruno Walter, Josef Krips and Wilhelm Furtwängler, and with soloists, besides Menuhin, including the singers Kathleen Ferrier, Julius Patzak and Hilde Gueden.

Menuhin had suggested that Furtwängler should be invited – even though the German conductor was under a cloud for his decision to work in his homeland during the war. Menuhin was convinced that Furtwängler was a good man and argued that the conductor demonstrated his integrity by insisting that émigré members of the Vienna Philharmonic, ousted in 1939 because they were Jewish, should rejoin to play with the orchestra during their London season. Still, “had I been more mature, I might have reflected more deeply” about backing his presence, Victor recalled.

In 1949 he made two moves that were to have a lasting influence on his life and work. By far the most important was his marriage to Lilian Shields, whom he had met in Schonfeld’s office. This brought him enduring happiness and gave him the ideal working partner. They undertook everything as a team. While he was at his best working behind the scenes, Lilian’s outgoing nature helped in making friends with their artists, and winning their loyalty.

Victor’s other important initiative in 1949 was the decision to branch out into ballet and to do so on a grand scale for mass audiences. He hired the old Empress Hall in Earl’s Court, and secured the great names of the postwar ballet era: Alicia Markova, Anton Dolin, Léonid Massine, Svetlana Beriosova. That year he also brought to Britain the two great Spanish flamenco dancers Antonio and Rosario. And the Vienna Philharmonic returned with Walter for what was to be Ferrier’s last performance.

As Victor’s reputation grew, his ambitions turned to the Soviet Union’s great artists. His father had heard the violinist David Oistrakh perform in Prague. He told Victor that this was an artist he had to have. But how could he persuade the Kremlin to let such a leading figure come to the west?

Negotiations finally began in 1953, after the death of Stalin, and Oistrakh came the following year – an occasion that Victor marked 50 years later by a concert with David’s son Igor and grandson Valery as soloists. In 1956, Mstislav Rostropovich came, for the first time, to Edinburgh and then to London, under the Hochhausers’ aegis. This was long before the cellist’s defection and Victor was now paying regular visits to Moscow to negotiate for folk dance troupes as well as classical soloists.

The Soviet authorities were far from overjoyed to be dealing with a Jew. But “They had little choice. I had the major orchestras in Britain under my management and I had the concert halls. In an attempt to discourage me, the Soviets increased the artists’ fees six-fold,” Victor recalled.

The relationship eased after an Anglo-Soviet cultural agreement was signed in 1957. With encouragement from the British government, the Hochhausers embarked on a series of remarkable exchanges between orchestras, soloists and ballet companies. The BBC Symphony Orchestra went with John Barbirolli to the Soviet Union, Poland and Hungary; the Bolshoi and Kirov ballet companies performed in London; festivals of Russian music with Shostakovich and many other Soviet artists were organised in Britain, too.

In 1972 the Hochhausers took their friends Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears to join the BBC Symphony to perform British music in the Soviet Union. The following year, the Hochhausers were also able to bring the Peking Opera to London for the first of many successful visits.

A long era of close cooperation with Moscow came to an end in 1974 when Rostropovich followed Nureyev and a clutch of other Soviet artists and defected to the west. The Hochhausers, already suspect because they had signed on Nureyev for performances in Britain, compounded their sins by giving the cellist the use of a flat in their office building in Holland Park. It took a long time for Victor to be forgiven. He was declared persona non grata; Moscow cancelled a tour because he was involved; formal memos replaced friendly correspondence addressed to “Dear Victor”.

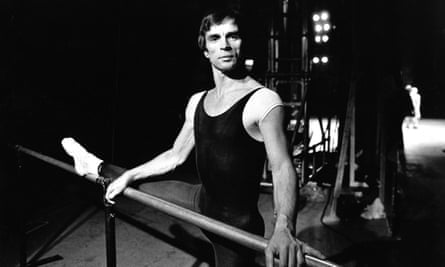

It no longer mattered greatly. Most of the great performers from the Soviet Union were now established in the west. Victor staged a dozen Nureyev festivals in London; Mikhail Baryshnikov performed there under the Hochhauser management; Rostropovich made frequent return appearances in Britain. The Hochhausers also broke new ground by bringing ice ballet to the Albert Hall, and Aida to Earls Court. And after Mikhail Gorbachev became Soviet leader in 1988, the Hochhausers were again in favour, and were able to organise exchange visits between Russian and British orchestras. In 1994 Victor was appointed CBE.

Victor and Lilian, both pillars of the Jewish community in Britain, also developed close ties with Israel, buying a house in Jerusalem and becoming involved in the country’s cultural life. They brought the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra to the UK, and helped to stage music festivals in Israel. Increasingly they focused on charitable work to promote Israeli interests.

However London, with their capacious, elegant Hampstead house set in extensive gardens, remained their much-loved home base. Going into the new century, Victor and Lilian still hovered around every event staged under the Hochhauser label to make sure that things worked smoothly and deal with the countless backstage dramas of visiting artists. The Mariinsky (as the Kirov had become) and Bolshoi ballet companies continued to appear in London, with the latter returning to Covent Garden this July. Victor also remained keenly interested in political developments at home and abroad.

He is survived by Lilian and their four children, Daniel, Mark, Simon and Shari.

Victor Hochhauser, impresario, born 27 March 1923; died 22 March 2019

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion