Holmes Report 29 Jan 2019 // 6:56AM GMT

View Part One of our Crisis Review here

View Part Three of Our Crisis Review here

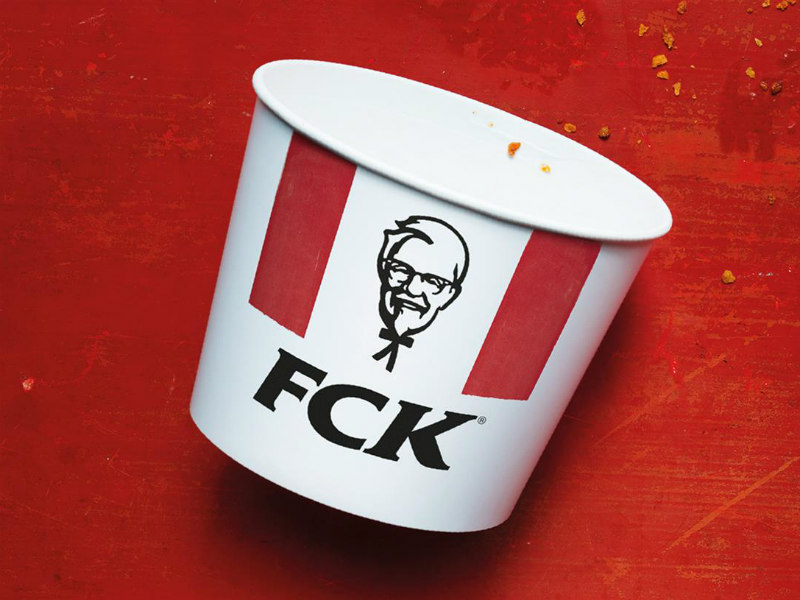

8. KFC’s Chicken Crisis

A chicken restaurant without any chicken is not an ideal situation in terms of bottom line or reputation. The chain went through an intense few weeks in the UK last year, after a logistics cock-up with a new delivery partner DHL, which took over the contract on Valentine’s Day alongside Quick Service Logistics (QSL).

Problems with deliveries of KFC’s highly perishable supplies started immediately: KFC started to shut down outlets after managers complained their chicken had not arrived, and by 18 February most of its 900 UK restaurants were closed.

KFC posted statements about the “delivery hiccups” in its closed shops and went into full-on social media response and media relations mode — as head of brand engagement Jenny Packwood told the Holmes Report, the team handled the equivalent of half its annual press calls in one week. The offensive culminated in a national newspaper advertising campaign as the restaurants slowly re-opened.

Frank co-managing director Andrew Bloch says that while the incident could have exposed the company to brand damage and disgruntled customers, the way in which KFC executed its PR strategy – with an experienced, fast-moving in-house team working closely with Freuds and Mother – was “nothing short of a masterclass in crisis communication.”

“Within hours of the initial problems coming to light, customers knew exactly what had gone wrong, how it was being resolved and, importantly, when it would be fixed,” he says. “Not only did KFC recognise mistakes had clearly been made, but they also used that to their advantage by injecting their own sense of humour and keeping the language straight-forward, clear and to the point.”

It would have been easy for KFC’s directors to hesitate, but the speed in which the team responded played to their advantage: they recognised the issues being experienced by customers immediately and began to communicate publicly as soon as facts became available. “KFC’s speed of response was key to managing the unfolding crisis successfully, and they successfully managed to not acknowledge blame until all the facts were known. It conveyed the right balance of responsibility and reassurance,” says Bloch.

In the aftermath of the distribution problems, KFC's use of humour on social media to respond to consumers directly, and then reorganising the letters of its brand name to spell FCK for a Cannes Lions-winning national advertising campaign, turned them “from crisis to credit, and led their handling of the situation to be widely and well-deservedly applauded,” says Bloch. — MPS

9. Bayer Inherits Monsanto’s Legal Woes

A change in ownership (Bayer closed its acquisition of competitor Monsanto in June) and a change in branding (it promptly made clear that the Monsanto name would be eliminated) will do nothing to clear up the reputational and legal issues that the German company inherited in this deal.

Bayer chairman Werner Baumann might have sounded optimistic: “Today is a great day: for our customers – farmers around the world whom we will be able to help secure and improve their harvests even better; for our shareholders, because this transaction has the potential to create significant value; and for consumers and broader society, because we will be even better placed to help the world’s farmers grow more healthy and affordable food in a sustainable manner.”

And he might also have acknowledged, obliquely, some of the issues: “Our sustainability targets are as important to us as our financial targets. We aim to live up to the heightened responsibility that a leadership position in agriculture entails and to deepen our dialogue with society.”

But it didn’t take long before a reminder that Monsanto’s history is toxic: Bayer’s stock took a 10% tumble in August after a California jury awarded $289 million to a former groundskeeper who said the popular weedkiller Roundup gave him terminal cancer.

Anthony Johndrow, co-founder and CEO of Reputation Economy Advisors was quick to explain the questions now facing Bayer management: “Two questions they need to answer: 1) why did you buy this company in the first place (lawsuits were already out there); and 2) what are you going to do about it now that it's your responsibility?”

Sylvain Charlebois, a professor in food distribution and policy at Dalhousie University, suggested broader problems on the horizon: “What remains unknown is how Monsanto’s past could potentially contaminate Bayer’s 156-year-old history…. In the public eye, the California ruling could trigger a new movement, a shift against the sector’s new menace, Bayer. With many cases to come, Bayer’s communications department will only get busier.”

Liam Condon, president of Bayer’s crop science division acknowledged the problem, “Just changing the name doesn’t do so much — we’ve got to explain to farmers and ultimately to consumers why this new company is important for farming, for agriculture and for food, and how that impacts consumers and the environment.” — PH

10. Paytm Falls to Earth

After shooting to fame amid India's famous demonetization initiative, Paytm endured a much tougher 2018, punctuated by two scandals that helped to undermine the mobile payments company's explosive growth.

First up was a sting operation by Cobra Post, which showed Paytm founder Vijay Shekhar Sharma’s brother Ajay Sharma claiming to be close to right-wing outfit RSS, and admitting that the company was asked to share user data with the Prime Minister's Office.

"The story around the sting operation did not go places because several leading media houses were also part of the expose and therefore it died a natural death," says Promise Foundation CEO Amith Prabhu.

A more debilitating crisis unfolded later in the year, however, when it was alleged that Vijay Shekhar Sharma’s secretary and communications VP Sonia Dhawan had hatched a plan with her husband and a colleague to extort Rs 20 crore ($2.73 million) from the company founder after breaching his personal data. The police arrested Dhawan and another colleague, amid little concrete information as to the nature of the plot, and its impact on the protection of user data.

"This was a rare instance of an allegation being made against the person who manages the company's reputation," notes Prabhu.

And while Paytm founder Sharma has tried to focus on a 'business as usual' message, the company has suffered from conflicting accounts of the conspiracy, in a country where rumours are relentlessly spread via WhatsApp.

"There is still lack of clarity on why the extortion bid was carried out and there has been no news on the matter ever since the arrest took place in end October," points out Prabhu. "The brand has been fairly silent ever since." — AS

11. Dolce & Gabbana Makes Friends in China

China is no stranger to foreign brands getting it spectacularly wrong but, even by those exalted standards, Dolce & Gabbana's fail was remarkably epic. The scandal revolved around a disturbingly ill-conceived video ad from the fashion brand, which featured a Chinese model struggling to eat pizza, spaghetti and a cannoli, alongside a condescending Italian voice over.

After vociferous criticism from Chinese netizens, the video was deleted within 24 hours. But things took a turn for the worse when Stefano Gabbana’s Instagram chat with model Michele Tranovo was posted online, with the company’s co-founder making racist remarks while criticizing China for the backlash against the ad.

As celebrity guests and models began abandoning D&G, the company was forced to cancel its flagship Shanghai fashion show on 21 November, less than three days after the initial ad aired. Soon, China's dominant e-commerce players were dropping D&G products from their retail sites, with many observers noting that it will take the company a very long time to recover from the self-inflicted scandal.

Meanwhile, D&G's crisis response also attracted criticism, with the company founders waiting 48 hours before posting an apology video. By that time, protests from China's netizens were already snowballing, much of which carried the kind of nationalistic slant that often underpins online outrage in the country.

"I think the biggest misstep by D&G in this unfolding scandal was that the response to the crisis was not vetted, let alone closely coordinated with the company’s communications team in China," says North Head senior executive director Robert Magyar.

Indeed, Magyar thinks the issues relating to the original advert "could have been handled relatively easily."

"We all accept that cultural and creative mistakes do happen," explains Magyar. "Recovering from damage caused by the leaked social media messages would have required a more personal and complex effort from the designers. However, all reactions / actions should have been discussed with local communications experts (internal and external) before taking any steps in order to fit with cultural expectations."

Instead, D&G's response looked like it was directed solely from HQ, without any communications advice in China. "One can argue that often there is no time for local input; I don’t agree with that," says Magyar. "A couple of hours or a day of delay in responding would have been a very small price to pay compared to the bungled efforts we have seen."

"Experienced PR teams should be able to handle crises and advise business leaders in these situations," concludes Magyar. "But it is important that leaders listen to their communications experts. Trying to wing a crisis response, no matter how good you are, will lead to business and reputation loss every time." — AS

12. McKinsey and Authoritarian Regimes

In 2017, McKinsey found itself embroiled in the South African controversy that ultimately claimed the life of UK public relations firm Bell Pottinger. There were social media protests against the management consulting giant, as well as a storm of negative media coverage in South Africa, where any business associated with the Gupta family was caught in the crossfire.

Far from subsiding in 2018, the controversy surrounding McKinsey and its clients intensified, with several reports focusing on the firm’s ties to authoritarian regimes. In November, South African authorities accused McKinsey of possible criminal wrongdoing in a report that condemns the consultancy’s work for the state power monopoly Trillian (a company with links to the Gupta family).

And then in December, the New York Times published a searing investigation into McKinsey’s role in laundering the reputations of authoritative regimes, including China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

According to the Times report: “At a time when democracies and their basic values are increasingly under attack, the iconic American company has helped raise the stature of authoritarian and corrupt governments across the globe, sometimes in ways that counter American interests.”

And it’s not just bad press: Senator Elizabeth Warren has urged the company to be more transparent about its advice to the Saudis: “I am concerned that McKinsey’s report on public perception may have been weaponized by the Saudi government to crush criticism of the kingdom’s policies, regardless of McKinsey’s intended purpose for the information.”

What’s particularly interesting from the PR industry’s perspective is that much of the work that McKinsey critics are focused on involves the kind of activities—public perception analysis, for example—that might more typically be handled by a PR firm. And indeed McKinsey touts its expertise in crisis management and rebuilding corporate reputation at its website.

For PR firms, this is a double warning: first, about increased competition from consulting firms, and second, about the potential for “reputation laundering”—especially for regimes with dubious records on human rights issues—to become an issue not only for the client but for the PR firms advising them. — PH

13. The Collapse of Abraaj Capital

Once seen as a titan of the private equity industry in emerging markets, with an investor list that included the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, the collapse of Abraaj was sudden and unforeseen. Abraaj’s fall, due to a business model that was described by Bloomberg as “highly unstable” combined with a lack of transparency with investors, has impacted Dubai’s own reputation as a financial hub.

While Abraaj’s founder Arif Naqvi built a reputation of rapid success for Abraaj, behind the scenes there were few compliance controls in place and, according to PwC, financial statements were often missing or non-existent. After months of denials and dodging of media questions, Abraaj collapsed, with debt of over a billion dollars.

Dubai’s financial regulator, the Dubai Financial Services Authority, is still suffering from the fallout; the regulator was accused of acting too slowly and not sharing enough information. Abraaj's collapse has also brought scrutiny onto the company's auditor KPMG, which earlier exonerated the firm from any wrongdoing

“The onus, whether we like it or not, is for the region’s private equity but also listed companies to demonstrate that Abraaj was an isolated case,” Alissa Amico, managing director of Govern, a governance advisory firm, told the Financial Times. “Regulators need to be attuned to the international interest in the case and communicate their investigation findings.”

If nothing else, the Abraaj case has helped to resurface longstanding concerns about corporate governance in the region. For example, the managing partner in charge of risk management at Abraaj was married to the founder’s sister. Meanwhile, Abraaj’s CFO at the time of the KPMG investigation had previously worked for the auditor.

"As the Mena region pivots away from its reliance on petrochemicals to a more diversified and open economy, its success in transforming its corporate governance culture from a relationship-based system to a rules-based one will be critically important for its long-term development," wrote CFA Institute Middle East/North Africa head William Tohme in Gulf News. — AS

14. The Tide Pod Challenge

Kids doing stupid things is nothing new, but the Tide pod challenge that reached its height in January 2018 was potentially lethal, too. Prompted by a social media dare, the challenge involved teens swallowing Tide pods — concentrated chemical-filled laundry detergent — and posting footage of the event, which usually involved a fair share of unpleasantries like gagging. In the first three weeks of January alone, the American Association of Poison Control Centers reported at least 86 cases of intentional misuse of the detergent by teens.

All of which put Tide owner Procter & Gamble, which already changed its packaging and added a bitter tasting chemical to make the pods less appealing to young children (six of whom died from ingesting the concentrate over five years) up against the wall, as it was charged with having to try to stop behavior which, for the large part, was out of its control.

“Tide finds itself in the crosshairs of a new breed of crisis — misuse of its product to create individual social celebrity,” said Careen Winters, MWWPR’s chief strategy and reputation officer. “This situation is becoming increasingly common, even coining the new term ‘selficide’ where people die in pursuit of extreme selfies, and is not something any crisis playbook of the past would anticipate.”

On top of that, P&G was in the precarious position of needing to act while not encouraging copycats by drawing more attention to the trend, said Scott Sobel, a kglobal senior VP whose expertise includes communications psychology. “But it is always a hard thing to determine the tipping point between a time when a trend will evaporate through disinterest or just explode because there isn’t any push-back,” Sobel said.

When it was clear that the tipping point was reached, which included widespread media coverage of the challenge, P&G stepped in in an effective and appropriate way, Sobel and Winters agree. NFL player Rob Gronkowski, who appeared in Tide pod ads, hit the web with a teen-targeted spot amplifying the message, “Do not eat.” Social media platforms took down videos on the dangerous behavior. P&G used the full range of platforms to get out warnings.

“P&G, to a degree, used the same communications steps that created the dangerous ‘challenge’ to tamp down interest and discourage stupid and destructive behavior. All propaganda isn’t negative if the communication theories are used for positive persuasive outcomes,” Sobel said.

Whether the Tide pod challenge is gone for good, however, is anybody’s guess. “It is too soon to say if the Tide challenge will be a passing social media phase or become a persistent dangerous behavior among teens like huffing, which prompted a significant reduction in aerosol cans across all manufacturers,” Winters said. "Unless they intend to eliminate pods from their product portfolio, Tide can only stay the course with proactively communicating about the risks of the behavior, perhaps with a boost from a broader, more relevant group of celebrities and influencers.” — DM

View Part One of our Crisis Review here

.jpg)