Nearly 70 years later, Florida redresses one of its ugliest episodes of racial injustice

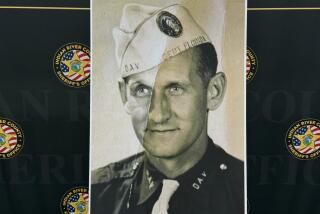

From the time she was a girl, Vivian Shepherd was haunted by the World War II photograph of her uncle Samuel, stern-faced with his Army cap slightly cocked. She asked her father about him, but he never wanted to talk.

One day, when Shepherd was in her late 30s, she saw a picture of her uncle in a PBS documentary on the battles of the civil rights movement. It was the photograph she knew so well.

She called her mother: “Why didn’t you tell me?”

Samuel Shepherd was one of the Groveland Four, a group of young black men who were victims of one of the ugliest episodes of the Jim Crow era in the South.

In 1949, they were accused of raping a white 17-year-old and variously subjected to mob attacks, beatings by officials and summary execution by the Lake County sheriff.

The story of the four men made national news but soon became a distant memory. “Groveland did not want anyone to know about it,” said Vivian Shepherd, now 57. “They just wanted it to go away and move on.”

Now it has been thrust back into the public consciousness. On Friday, in one of the first acts of newly elected Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, he and the other three members of the state clemency board unanimously granted pardons to the Groveland Four.

“I don’t think there is any way that you can look at this case and see justice was carried out,” DeSantis said at the hearing.

The incident began nearly 70 years ago on July 16, when Norma Padgett and her husband said that their car broke down and that they were accosted by four black men. Willie Padgett said he was beaten by the side of the road.

Norma wandered into Okahumpka, 15 miles north of Groveland, the next morning and told a man she had been abducted. She later claimed she had also been raped.

The Padgetts led police to Shepherd and to Walter Irvin, who told authorities they had tried to help the couple fix the car but gotten into a minor scuffle and left. Two other young men were named by authorities, who described them as known troublemakers.

As word of the allegations got out, the Ku Klux Klan descended on Groveland, shooting at the houses of black people or burning them down.

“The Klansmen came looking to kill my whole family,” Vivian Shepherd said. “They had to run for their lives, spending days hiding in the orange groves and never returning home again and moving to Orlando. My grandfather not only lost their home, but he lost his son.”

John Griffin, who was 5 at the time, said his father took the family to nearby Montverde when the Klan started to arrive.

His dad “said he was coming back to our house and if any white man strikes a match to burn his house down, he was going to kill him,” said Griffin, who is now 74 and recently retired from the Groveland City Council.

Howard King, whose family settled in the area in the late 1800s and brought black workers from Baltimore, remembered the chaos as “a bunch of rednecks who went crazy.”

“They had the power, they had the support of the sheriff,” he said. “They were waiting for one incident.”

When one of the suspects, 25-year-old Earnest Thomas, fled north, Sheriff Willis McCall appointed a posse, which chased him down and left his bullet-riddled body in the woods 200 miles away.

The fourth suspect, Charles Greenlee, 16, was beaten until he confessed and was sentenced to life in prison — even though he had been in custody for a gun violation at the time of the alleged attack.

Shepherd was tortured into making a confession and tried with Irvin. Jurors were never told that a doctor who examined Padgett was unable to conclude that she was raped.

The two men, both 22, were convicted and sentenced to death. Thurgood Marshall — then a lawyer working for the NAACP, later the first black justice on the Supreme Court — took up their case and persuaded the Supreme Court that they had not received a fair trial and to order a new one.

The sheriff picked up the two men at the state prison to drive them back to Lake County for the retrial. They were handcuffed together when, according to McCall, he stopped the car to check a tire and they tried to escape, so he shot them.

Shepherd died at the scene of a gunshot wound to the head.

Irvin played dead to avoid more gunfire. He had to ride to the hospital in a car provided by a black-owned funeral home because an ambulance refused to transport black people.

Irvin was eventually retried, convicted and again sentenced to death.

In 1955, after the prosecutor said he had doubts about the conviction, the governor commuted the sentence to life in prison. Irvin was paroled in 1968 and died a year later of what were determined to be natural causes. He is buried in one of Groveland’s all-black cemeteries.

Vivian Shepherd wasn’t the only one who hadn’t heard this sordid piece of local history.

Many who grew up in this small central Florida town, originally built on the industries of citrus, lumber and turpentine, didn’t know for decades.

Then in 2013, the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction went to the author Gilbert King for his account of the saga, “Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America.”

For some in the town, the book was a call to action. Two years ago, the Groveland City Council made a proclamation apologizing for what happened to the four men.

Greenlee, who had survived the longest, almost lived to see it. He was paroled in 1962, moved to Nashville and died in 2012.

The Florida Legislature called for the exoneration of the Groveland Four in 2017, asking then-Gov. Rick Scott to put the issue on the clemency board docket. In his remaining time in office, Scott never did.

When asked for an explanation early this month, Scott’s press secretary said they were “reviewing our options,” and then never got back to the Los Angeles Times before Scott left state office Tuesday.

The population of Groveland has grown from 1,000 to 14,000 since 1950, and today the city is 47% white, 25% Latino and 23% black. In some ways, the town is still coming to terms with its past.

Despite the publicity, the Groveland Historical Society, a cramped building of clippings, mementos and sports trophies, has no mention of the Groveland Four in any of its displays.

“To not have it in the museum is like trying to hide a rotting corpse,” said Griffin, the former councilman. “You can try and keep dirt on top of it and keep it hidden from the public, but you’ll eventually start to smell it.”

The larger Lake County Historical Society in nearby Tavares features one small exhibit.

“The Groveland Four is a part of Lake County history, and we want to cover it, good and bad,” said Marli Wilkins-Lopez, who works there. “I think that there are so many new people that unless they were history buffs, they probably didn’t even know this happened.”

At the same time, she said, “a lot of old-timers in Lake County want to say that this is history, it’s over, it’s done, we don’t need to talk about it.”

The exhibit is housed in the same building as the sheriff’s department, where one wall features portraits of all the former sheriffs, including McCall.

In 1972, he was serving his seventh term as sheriff when he was indicted for the murder of a mentally disabled black prisoner while in custody. The indictment said McCall kicked and beat the man, causing his death.

McCall, who had bragged about having stayed in office so long despite being investigated dozens of times, was acquitted by an all-white jury. He was defeated in the next election.

The county named a road for him in the late 1980s but renamed it in 2007, 13 years after his death at age 84.

Norma Padgett, 86, is the only one involved in the Groveland Four saga who is still alive. She lives in Georgia and had not spoken publicly about what happened since Irvin’s second trial — until Friday.

“I am the victim,” she told the clemency board. “I was 17 years old and it never left my mind. … You all just don’t know what kind of horror I’ve been through for all these many years.

“I do not want them pardoned — no, I do not.”

The board disagreed. “I hope that this will bring peace to their families and their communities,” the governor said after the vote.

But Mike Hein, the Groveland city manager, said he doesn’t see the town achieving that anytime soon.

Hein would like to organize community discussions about the Groveland Four, but not have them run by city government. He’s also in favor of some type of recognition of the past.

“There should be some way to reflect what happened,” Hein said. “It could be a memorial or something in the historical society. You could put markers where some of the incidents took place. I think someday there will be.”

Vivian Shepherd has stayed in Lake County and lives in nearby Clermont.

“We just want closure and not push it aside anymore,” she said. “You can’t bring them back. You can’t change what happened, but you can clear our names. If they call them rapists, then our name becomes that of a rapist. … I’m grateful to God that somebody heard us.”

Cherwa is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.