In the early 1950s my childhood cultural diet was largely made up of westerns and British war films, complete with the obligatory American and British heroes. Then, one week, a curiosity showed up at a local cinema as the second feature.

It was a 1948 Franco-Norwegian docudrama, Operation Swallow: The Battle for Heavy Water (Kampen om Tungtvannet). This time the good guys were Norwegians, and mostly they played themselves. One notable exception was the leader of that epic mission, Joachim Rønneberg, but he had featured prominently at the film’s premiere in Oslo, alongside King Haakon VII.

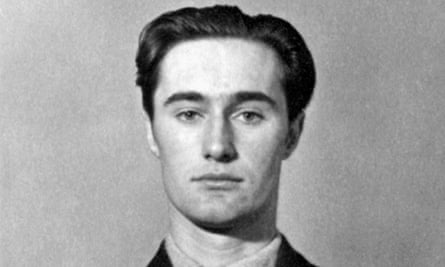

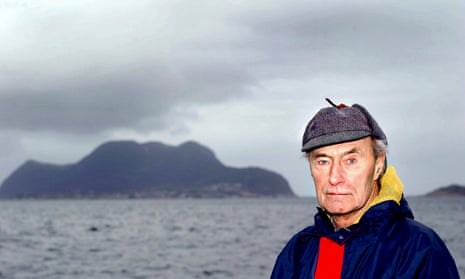

Rønneberg, who has died aged 99, led an operation that demanded extraordinary courage and dedication from its all-Norwegian team, and which later formed the basis of another, more widely known but less accurate film, The Heroes of Telemark (1965), starring Kirk Douglas and Richard Harris.

In the winter of 1942 Lieutenant General Leslie Groves, the newly appointed boss of the ultra-secret Manhattan Project to develop an atomic bomb, asked the British to move on their plans to destroy the German-controlled deuterium oxide “heavy water” plant at Vemork in Telemark, Norway, which was considered vital to the Nazi nuclear programme.

Four Norwegian commandos had been sent in as an advance party on 18 October 1942, as part of Operation Grouse. The British followed this on 19 November with 34 glider-borne demolition experts. In appalling conditions the gliders crashed, and the 14 survivors were promptly executed by the Germans.

It was then that RV Jones, director of intelligence for the British Air Staff, had to decide whether to launch another attack. It was “one of the most painful decisions that I had to make,” he said, but the decision was to try again.

So on 16 February 1943, the 21-year-old First Lieutenant Rønneberg and the rest of his six–strong party were parachuted, in total darkness, from a Stirling heavy bomber, flying at 1,000ft, on to the icy wilderness that was the Hardanger plateau. They were 35 miles from Vemork. Operation Gunnerside had been activated.

Four days of Arctic blizzard followed, but by pure luck the men blundered into a hut where they could shelter. On 22 February the sky cleared – and they then encountered a skier who turned out to be a Nazi-supporting Norwegian. Later that day, having encountered the four-strong Grouse group, who had been lying low in the field since the first failed mission in November, Rønneberg persuaded his men that the lone skier should not be killed, and, swearing him to secrecy, released him.

What followed was described by General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, the commander of the German occupying forces in Norway, as “the best coup I have ever seen”. The hydroelectric plant was located on the side of a precipitous gorge above the River Maan. Since the failed attack the previous November “guards were now posted around the factory, and the garrison had been increased to 200 troops,” wrote Giles Milton in The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare (2016). “Four anti-aircraft guns had been installed, along with banks of machine guns, and a network of searchlights around the place.”

By 27 February the 10 men were within three miles of their target. There was, they had discovered, a disused railway along the side of the gorge, providing a way into the factory. Claus Helberg, from the Grouse team, was sent by Rønneberg to reconnoitre the site. He announced that there was an ice bridge above the river, which, if it held, would provide them with access – and exit.

In mid-evening the commandos set out, carrying five tommy guns, grenades, compasses, shears, explosives, fuses – and cyanide pills. When they were halfway down they first glimpsed the seven-floor Norsk Hydro. They crossed the river and by 11.30pm, having scaled the heights, they were awaiting the change of guards.

They divided themselves into two groups, with Rønneberg and Fredrik Kayser heading down to a lower platform and then on via a cable shaft into the outer plant room. Arriving in the electrolysis room, they took a terrified Norwegian guard prisoner, and soon after were joined by two other commandos. The charges were set, their timings reduced from two minutes to 30 seconds, and the party departed, doors locked behind them, while the Germans remained oblivious to the muffled explosions that ensued.

It was only when the saboteurs had passed the ice bridge that the Germans raised the alarm, and soon Rønneberg and most of his comrades, back on skis, were making an arduous but successful journey to neutral Sweden. It had been one of the most important and successful missions of the second world war, and their actions had effectively destroyed the heavy water production facility. Following subsequent allied bombing raids on the plant, the Germans ceased operations there.

Operation Gunnerside was not the end of Rønneberg’s wartime exploits. He destroyed a railway bridge using plastic explosives, disrupted communications and supply lines, and remained in action until close to the end of the second world war.

Born in Ålesund, a town on the west coast of Norway, Joachim and his brother, Erling, were the sons of Alf Rønneberg and his wife, Anna (nee Krag Sandberg), and both young men would become prominent in the resistance. After being educated at Ålesund secondary school and, from 1935 to 1938, at the Latiner high school, Joachim moved to Oslo, spending a year studying economics on the assumption he might go to Oslo University before taking over the family’s long established merchant and freight business.

He had not long begun his national service, working as a military surveyor, when the German occupiers arrived in April 1940, and within a few months he had escaped by boat to Scotland and enlisted in the Norwegian Independent Company, a British Special Operations Executive group formed to launch commando raids in occupied Norway. At that stage Rønneberg had no military knowledge, but he quickly impressed his instructors with his aptitude and complete calmness under pressure.

After the war Rønneberg joined NRK, Norway’s state broadcaster, in 1948, and remained there as a journalist and director until his retirement in 1988. He received many decorations, including Norway’s highest gallantry award, the War Cross with Sword, the British Distinguished Service Order, the French Croix de Guerre, and the American Medal of Freedom with Silver Palm.

He married Liv Foldal, who taught arts and crafts, in 1949; she died in 2015. He is survived by their three children, Jostein, Asa and Birte.

Joachim Holmboe Rønneberg, soldier and journalist, born 30 August 1919; died 21 October 2018

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion