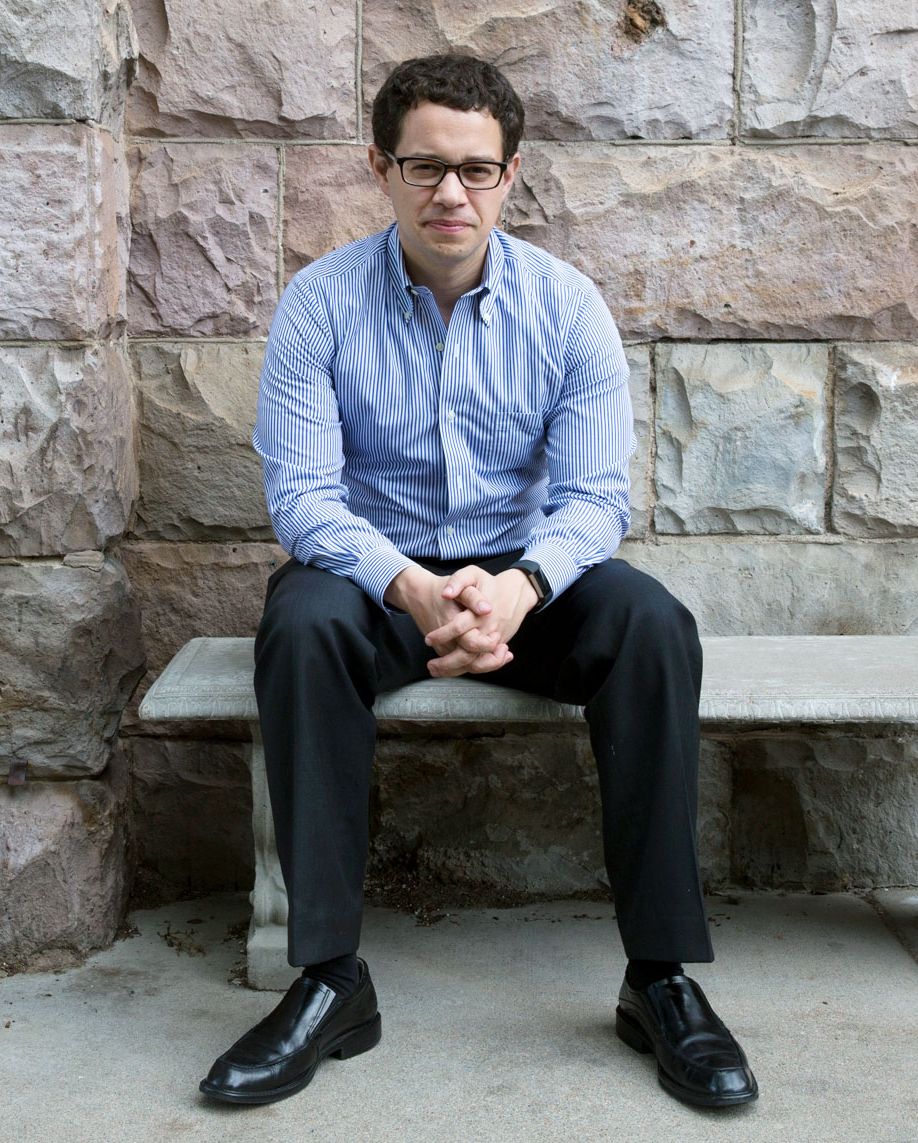

Things were looking bad for Andrew Freedman in March 2014. It was just two months after Colorado became the first state to make cannabis fully legal, and Freedman had been tasked with seeing cannabis safely into the hands (and lugs, and bellies) of Coloradoans, when a Congolese exchange student, Levy Thamba, ate too much of a cannabis cookie, freaked out, and jumped to his death from a balcony in Denver. Weed was barely ten weeks on the open market and it had claimed a victim.

"That was the hardest phone call I ever got," says Freedman, a veteran of the cannabis legalization wars now at the ripe old age of 35. When Thamba died, Freedman was a year into his role as the first director of marijuana coordination in Colorado — marijuana czar, for short. When he got the job, he had zero prior experience with marijuana policy and very little with the drug itself. ("It's not a significant part of my life," he demurs when asked about personal use.) But somebody had to be the one to create the first robust, legal pot market in the country. And with a couple years of experience as chief of staff for Colorado's lieutenant governor, Freedman turned out to be that guy. On that day in March, he also ended up being, in a tangential way, responsible for its first victim and, perhaps, the crash and burn of the entire marijuana movement.

As Freedman tells this story in his Denver apartment, he himself is a little wide-eyed at where he ended up. Essentially, he's a Harvard-educated lawyer who never wanted to practice law. In 2010, he was about to ship off to Australia to learn how to surf when his brother said, Come back home to Colorado and work on the governor's campaign instead. So he did and finally made sense of that law degree: He'd help enact new laws and maybe build a better world while he was at it.

Marijuana might seem to be an odd place to start on that quest. But if you view it, as Freedman does, through the lens of social justice, or economic potential, or public health, you get a picture of his mission. It's one that doesn't exactly dovetail with how the Drug Enforcement Agency sees things. The DEA still lists marijuana as a schedule-1 drug, meaning it has "no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse." Same as heroin. Cannabis remains illegal on the federal level, although 31 states have approved some version of medical marijuana and nine plus the District of Columbia permit recreational use.

Which leaves use in a legal jumble. Colorado residents are with their rights to fire up a doobie at their mountain home in Estes Park, but they could be arrested for the same if they decide to cross the line into nearby Rocky Mountain National Park, which is on federal land. You’re an upstanding citizen when you pack your vape pen in your carry-on at home in Los Angeles, but you become a felon when you drive onto federal turf at LAX. And don’t even think about shipping cannabis gummies to your brother via the U.S. mail, a violation of federal and interstate-commerce laws for controlled substances.

Of course, pot isn’t apple pie. It’s an intoxicant that makes people do stupid things sometimes. There are lots of questions to be answered about driving under the influence of pot, for instance, and use by young people might affect their brains in negative ways, long term. It may raise the risk of heart attack and stroke. The fact is, the legalization cart bolted downhill before the research horse was out of the biomedical barn. And it rolled right into Freedman, the state of Colorado, and a body on the sidewalk.

Before it was outlawed at the turn of the last century, cannabis was a common ingredient in medicines and was prevalent in the form of hemp, an industrial fiber. Eighty years later, potential therapeutic applications would act as the camel’s nose under the legal-cannabis tent, because it’s hard to deny weed therapy to a kid like Charlotte Figi. She was a Colorado Springs resident who suffered from Dravet syndrome, a rare form of epilepsy, and her desperate parents sought alternatives to the powerful drugs that failed to stop her seizures. She was helped by a cannabidiol strain of cannabis that came to be called Charlotte’s Web. (Cannabidiol, aka CBD, is one of the 142 possibly therapeutic compounds isolated from the cannabis sativa plant. Tetrahydrocannabinol—or THC—is even more famous as the one that makes you high.) Young Charlotte’s case, and treatment, were featured prominently on CNN in 2013, when Sanjay Gupta, M.D., reported on the healing powers of weed. On prime time. All of a sudden, the weed story wasn’t about addled dopers; it was about the healing power of this miracle plant.

Soon Charlotte’s moving story was set alongside those of veterans who were moving to Colorado for hemp help with their post-traumatic stress syndrome and other pains of war, alongside glaucoma patients who found relief in pot, and alongside former NFL players who swore that cannabis was a useful alternative to opioids, or was helping them with brain injuries.

Intrigued by the apparent success of these home-grown, home-tested remedies, pharmaceutical companies began conducting their own research. One of the first cannabis-derived drugs, Epidiolex, a pure CBD extract, was approved by the FDA in June to help with two childhood-seizure disorders, including the one that afflicted Charlotte Figi. And keep in mind, CBD is just one of the many cannabinoids found in marijuana. So we’re only beginning to sniff at its healing potential—and maybe even at its harms—as this yet-to-be-well-researched plant gallops into the mainstream.

Freedman came to the czar role fresh off a job as chief of staff for the lieutenant governor of Colorado, but his immediate prior experience was failing mightily at a task set for him by Governor John Hickenlooper. The idea was to coordinate early-childhood education in Colorado, and Freedman was tabbed as the guy with the interdepartmental skills to pull it off. But the voters overwhelmingly turned down the tax bill that would have funded the initiative.

So there was Freedman, post–educational disaster, on election night 2012, watching the results roll in. Governor Hickenlooper had come out against Amendment 64, the ballot measure that would allow the state to amend its constitution to permit the recreational use of marijuana. (The state had previously approved it for medical purposes in 2000.) But the people rose to approve it, 55 percent to 45. Accepting the marijuana mandate, the governor quipped, “This will be a complicated process, so don’t break out the Cheetos or Goldfish too quickly.” At the time, Freedman remembers thinking, “Somebody’s going to have to do a lot of work on this.”

That somebody turned out to be Freedman, of course. Governor Hickenlooper asked him to manage the transition to legal sales of cannabis on January 1, 2014, fourteen months after the vote. With the governor’s imprimatur, Freedman called ten department heads and their key staff into a room, they laid out their goals, and the work began.

Legalization was, as you’d expect, a regulatory rat’s nest. The team had to create an entirely new retail industry to sell legal weed. They had to figure out how to tax this hot new product and manage all the groups that wanted a piece of that new income, all while the Department of Revenue was inundated. “They had the least amount of infrastructure and expertise they would ever have,” Freedman says, at the exact moment they had pileups of people who wanted licenses.

The group had to create and police a new agricultural sector to safely grow weed, and make sure excess buds didn’t leak over the line into Nebraska and Wyoming, where pot was still prohibited. They’d be the ones to see that the plants met U.S. Department of Agriculture standards for pesticides on consumable plants. It’s hard to overlook the irony of the challenge in recruiting and vetting all the workers for this new industry, seeing as the most qualified among them had probably been in violation of federal law for years.

What wasn’t immediately obvious: Beginners didn’t want to smoke pot; they wanted to eat it. The medical market was mostly made up of marijuana smokers, Freedman notes. But smoking makes you cough, and stink. No wonder, then, that the edibles market was the first to really take off among “naive users”—those with little experience of the drug but who wanted in on the fun. How do you make it so they can get high but not injured? Levy Thamba made that a poignant question indeed.

The more you pull at strands of the legalization web, the more respect you have for Freedman’s job as chief spider in the middle of it. The only way to get the job done was through the coordinated efforts of everyone at that table in the state capital, each department taking ownership of its new mandate from the people of Colorado, and making sure it didn’t harm the very citizens who had voted legalized marijuana in. Keep in mind that 45 percent of voters didn’t want it, including their governor. So it took a major finesse job to herd the legislative cats, bring industry on board, and see that enforcement would be protective and positive. If could have been a giant mess, in fact, if it weren’t for the organized, inclusive mind at the center of it all. Maybe you didn’t think government could pull off something like that anymore. But Freedman did.

From the start, says Freedman, his group single-mindedly maximized the potential upsides of legalization—creating safer, healthier adult access to marijuana through the dispensaries, and creating lots of jobs and tax revenue for Colorado, while diverting police away from the minorities who’d previously been targeted in busts. They did all this while also scenario-planning the downsides: accidental ingestion by kids and dogs, a feared mushroom cloud of teenage potheads, and worries about overconsumption among the primary smokers—young men. And all of this was under intense scrutiny: “A million articles a day,” says Freedman.

Into that full-court press leapt Levy Thamba. Freedman didn’t know if he would be an isolated incident or if death-by-edibles numbers would jump as well. But here’s where Freedman’s particular genius for the czar job came to the fore: “For every major decision, we agreed we’d have a transparent stakeholder process; we’d take the best lessons we have from prescription drugs, tobacco, alcohol, and we’d do our best,” he says. “And the other thing we all agreed to is when we’re wrong, we’ll just say we’re wrong.”

So Colorado copped to the error of unregulated labeling for edibles. Concerned government and cooperative industry came up with immediate fixes: Packages were more clearly marked, they contained carefully regulated doses of 10mg THC per single serving (Thamba’s cookie had 65mg), and the public-service ads and handouts cautioned people to “start low, go slow.” The surprise was that people did exactly that. For once, government and the governed were in sync, and the press turned to other stories.

There were still concerns, of course, but the state was doing okay. According to Daniel Vigil, M.D., who monitors the public-health impact of legalization for the state of Colorado, the daily-use numbers for marijuana are still well below those for alcohol and tobacco, which are proven killers. Additionally, the youth-usage rates have remained relatively unchanged before and after legalization, and the homeless numbers, another big worry, are in line with the national increase, in a state with thousands of new residents, a booming economy, and increasingly competitive housing—so they’re likely not a result of pot plantings.

“I’m proud of what Colorado did in those three years,” says Freedman. He helped the Centennial State’s citizens survive and then thrive with their big experiment, and their hard-won lessons will now be helping others manage their own legalization adventures. “It could have torn the state apart in the political environment we have right now. But I don’t think it’s time to spike the football. In fact, I think the major challenges are still ahead.”

On his fret list: a plunge in pot prices, which could lead to overconsumption. Overdeveloped home grows, which could bleed into nearby states where pot is still illegal for recreational use. Ensuring that the jobs and tax revenues that come from legal marijuana end up benefiting the minority and low-income communities that were historically punished by drug-law enforcement. And, crucially, how to do necessary research on cannabis—as a therapeutic treatment, as a potentially addictive drug—when it’s still illegal nationally.

The need for more research is indeed critical. A study published in the Pharmacology Review suggests that cannabinoids could be a potential therapeutic tool for everything from “mood and anxiety disorders, movement disorders such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease, neuropathic pain, multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury, to cancer, atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, stroke, hypertension, glaucoma, obesity/metabolic syndrome, and osteoporosis, to name just a few.” But as much as people like to tout the health benefits (just Google your issue and cannabis and you’ll find someone swearing it helps), the scientific community honestly doesn’t know much about what it might do, good or bad. All those large, double-blind, incontrovertible studies proving cannabis will make lives healthier? We don’t have those yet.

While the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 essentially kept pot from widespread use and the Controlled Substances Act officially made it illegal in the 1970s, they both also successfully kept it out of the hands of U.S. researchers, who are now eight decades behind on their hemp homework. There’s only one place, the University of Mississippi, where scientists can get research-grade cannabis (with standardized and verified THC and CBD content), and they’re limited by the quantity and quality of what the university can grow.

Ironically, legalization itself may be stalling scientific understanding rather than advancing it, according to Ryan Vandrey, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, who has been studying cannabis for nearly 20 years. “How botanical medicines are developed, historically, is that you try to figure out which exact chemical is driving a very singular effect on a very singular health condition,” he says. “Then you figure out the best route of administration and the best dose that helps the most people safely. That’s not being done for cannabis.” He doesn’t hold out much hope that this type of research will be completed anytime soon.

“When a drug is available on the shelves, why would anybody go through that painstaking and very expensive process of figuring out exactly which part of this plant is helping one health condition?” he says. People may just say what the citizens of Colorado did, in essence: “We’ll experiment on ourselves, thank you.”

Meanwhile, the approval avalanche is on across the U.S.—61 percent of Americans now favor full legalization (medical and recreational) and Canada launched full national legalization as of October 17. In light of all that, and at the urging of Governor Hickenlooper, Freedman left the Colorado statehouse. “He told me, ‘Every state I go to, they’re asking me a thousand questions about marijuana. Everybody needs to be briefed the way that I’m being briefed. You gotta go.’” So he went. Freedman has set up a consulting firm and is now living in California, a new cannabis market of nearly 40 million people. If it were a country, it would be the fifth-largest economy in the world. When Freedman isn’t working to make the Golden State greener, he’s consulting with governments that are considering legalization.

The domino effect is clearly on, as other states and countries digest Colorado’s experience—tax revenues and jobs up, minority arrests down, negatives negligible—and decide they’d like a hit of that (even though, keep in mind, there’s no conclusive science on whether it’s good for you or not). The so-called big impediment—national legalization—might even be a good thing, according to Freedman: It keeps a Big Tobacco situation away. When it comes to marijuana distribution, smaller is better. It keeps the system from being awash with cheap, abundant weed. And tax revenue from pot can benefit strapped local governments.

As befits a guy who helped open Pandora’s pot stash, Freedman thinks a lot about the welfare of the public. Ask him if he’s a health innovator and his answer is equal parts modest and wonky: “I would not consider myself a public-health expert,” he says. “I can get the public-health experts to weigh in on policy in an effective manner, and to actually bring those groups together to influence policy.” And in Colorado’s case, lead the grand cannabis experiment.